Spirituals: Double Entendre

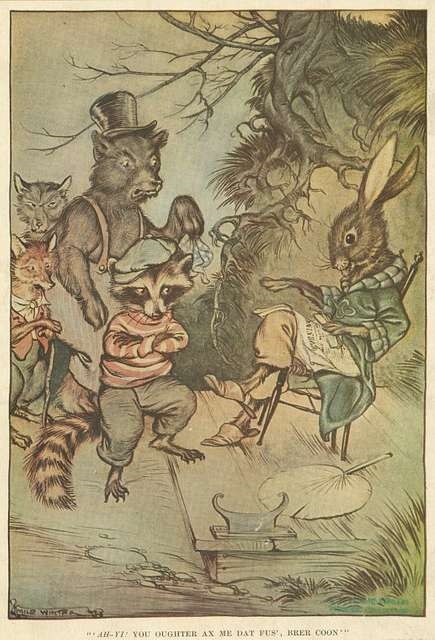

An African precedent for this practice is called "double entendre." African myths, riddles, and proverbs are filled with stories of weak but clever animals outwitting their stronger counterparts, some of which found public expression in the Brer Rabbit stories (Ames 1955, 140-141). Naturally, those tales and their secret meanings found their way into the spirituals and work songs of the slaves. "Communication in song was certainly safer than direct talk," writes Russell Ames, "and slaves could further disguise their messages by singing about animals instead of about themselves. Almost any apparently innocent and comical lines could be used to pass along word of an illegal meeting and to advise caution" (Ames 1955, 140-141).

Years after slavery, the use of animal characters to convey deeper truths remained strong in the African American community. The following bit of poetry says much about the Black ability to survive as strangers in a strange land:

De white man don drive off e Injun, Done mos' drive off de fox, But Brer Rabbit, he say he gwine stay.

(Lovell 1972, 172)

Spirituals: Signifyin(g)

It was not long before what began as a survival mechanism among slaves became, if not a weapon, then at least a treasured asset. Henry Louis Gates, Jr., coined the word "signifyin(g) ![]() SIDE NOTE"Signifyin(g) is a way of saying one thing and meaning another; it is a reinterpretation, a metaphor for the revision of previous texts and figures, it is tropological thought, repetition with a difference, the obscuring of meaning-all to achieve or reverse power, to improve situations, and to achieve pleasing results for the signifier" (Gates 1988, 53, 88).]" to describe this phenomenon. Signifyin(g) refers to the particularly African American practice of combining a multitude of meanings, including speaking on multiple levels, especially in the presence of Whites. It also involves self-reference; identification of (apparently) arbitrary words, phrases, or concepts; the sheer joy of language; the ability to riff or improvise around someone else's words or music; and the ability to co-opt words and concepts that mean something to Whites and transform them into something entirely different (Gates 1988, 46-50).

SIDE NOTE"Signifyin(g) is a way of saying one thing and meaning another; it is a reinterpretation, a metaphor for the revision of previous texts and figures, it is tropological thought, repetition with a difference, the obscuring of meaning-all to achieve or reverse power, to improve situations, and to achieve pleasing results for the signifier" (Gates 1988, 53, 88).]" to describe this phenomenon. Signifyin(g) refers to the particularly African American practice of combining a multitude of meanings, including speaking on multiple levels, especially in the presence of Whites. It also involves self-reference; identification of (apparently) arbitrary words, phrases, or concepts; the sheer joy of language; the ability to riff or improvise around someone else's words or music; and the ability to co-opt words and concepts that mean something to Whites and transform them into something entirely different (Gates 1988, 46-50).

"Signifyin(g) is Black double-voicedness Asserts that African American literature is a combination of two voices that provides African American literature a rich identity. It means to speak both the language of the dominant culture and the language of the subordinated culture.; because it always entails formal revision and intertextual relation," Gates writes, "and because of Esu's double-voiced representation in art, I find it an ideal metaphor for Black literary criticism for the formal manner in which texts seem concerned to address their antecedents. Repetition, with a signal difference is fundamental to the nature of Signifyin(g) . . ." (Gates 1988, 51). Gates calls Signifyin(g) a "rhetorical practice" designed to protect sensitive information from outsiders (Gates 1988, 52). An instinctive understanding of this "practice" enabled slaves standing in front of overseers to feign ignorance and yet at the same time exchange valuable information through spirituals, work songs, and "pidgin" English. Or, as some older African Americans once said, "A heap see and a few know" (Kirk-Duggan 1997, 80).

Source: Oregon State University

Watch this video for a classic example of the "rhetorical practice" of keeping sensitive information from outsiders can be seen in the jive talk of jazz musician Cab Calloway. Although this example is in a more contemporary era, it brings clarity and understanding concerning signifyin(g) Spirituals, then, besides their undeniable religious mandate, "communicate ethnic identity" within the community:

Cab Calloway narrates "Minnie the Moocher & Many Many More" 1983 documentary [ 00:00-00:00 ]

. . . Black slaves used the spirituals to imitate life, to remake reality, and to know art as life. This experience of true soul theology or self-consciousness, often cloaked in silence for the sake of survival, comes alive in the Spirituals as function, useful art affording glimpses of true humanity. Slave bards produced more than six thousand extant Spirituals despite the prohibition of slave education. So many exist because there was so much to say, to share, in codes that those beyond the community were not privy to understand.

(Kirk-Duggan 1997, 79-80)

Howard Thurman

For [the slaves] the 'troubled waters' meant the ups and downs, the vicissitudes of life. Within the context of the 'troubled' waters of life there are healing waters, because God is in the midst of the turmoil. Do not shrink from moving confidently out into the choppy seas. Wade in the water, because God is troubling the water.

Booker T. Washington

The plantation songs known as "Spirituals" are the spontaneous outburst of intense religious fervor. They breathe a child-like faith in a personal Father, and glow with the hope that the children of bondage will ultimately pass out of the wilderness of slavery into the land of freedom.