Spirituals: Based on Biblical Characters (Continued)

A century later, there would be an eerie parallel when members of the underground Church in Nazi Germany heard sermons about the God-protected little boy David and the mighty giant Goliath. In that one-sided battle, the persecuted Confessing Christians understood what the symbols meant, even if the Gestapo spy in their midst did not. As long as the pastor stayed within the framework of the Old Testament story, he could not be denounced as "subversive" (Dixon 1976, 23).

Despite the danger, Frederick Douglass recalled singing songs of deliverance in front of his abusive owner, "Mr. Freeman."

A keen observer might have detected in our repeated singing of something more than a hope of reaching heaven. We meant to reach the north-and the north was our Canaan...was a favorite air, and had a double meaning. In the lips of some, it meant the expectation of a speedy summons to a world of spirits; but, in the lips of our company, it simply meant a speedy pilgrimage toward a free state, and deliverance from all the evils and dangers of slavery.

(Southern, Readings 1983, 87)

Canaan

O Canaan, sweet Canaan

I am bound for the land of Canaan

I thought I heard them say

There were lions in the way

I don't expect to stay

Much longer here

Run to Jesus-shun the danger

I don't expect to stay

Much longer here

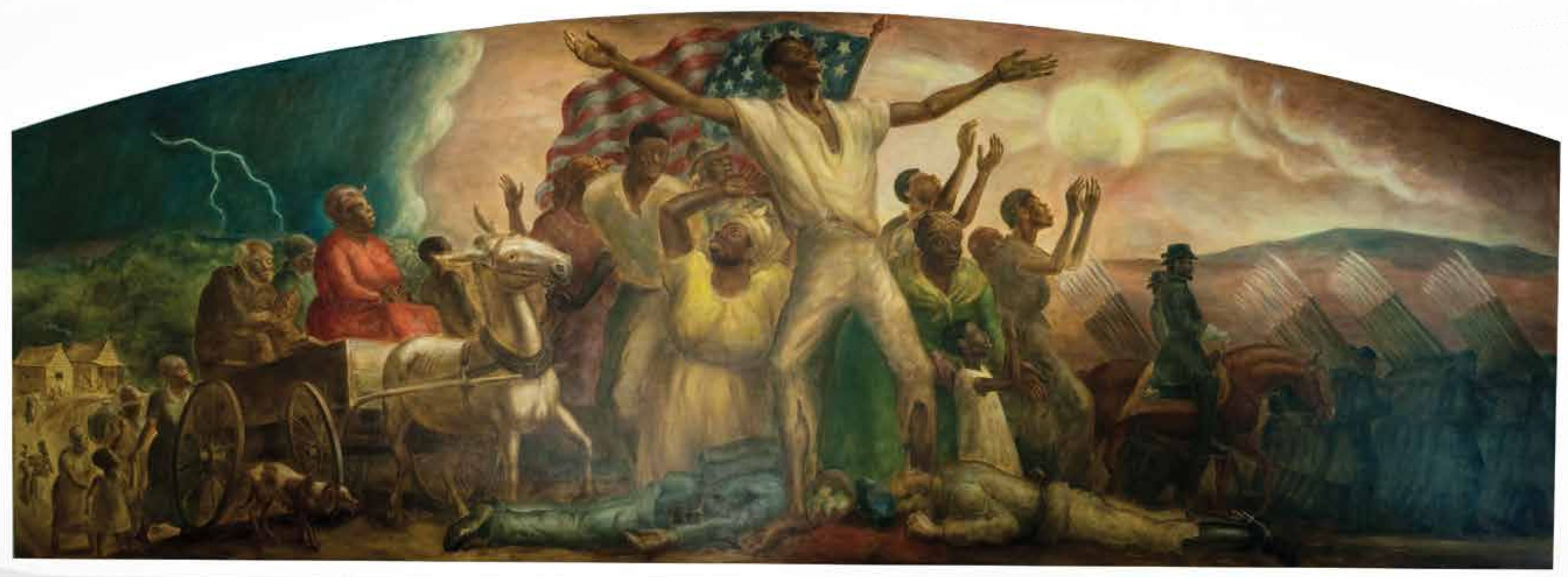

It is not surprising, then, that perhaps the most common image found in the spirituals is the deliverance of a chosen people. The core message of the spirituals may indeed be God's ultimate liberation of the suffering slave. "The message of liberation in the spirituals is based on the biblical contention that God's righteousness is revealed in his deliverance of the oppressed from the shackles of human bondage," writes James H. Cone (Cone 1972, 33-35).

The spirituals' universe revolved not around the man and woman in the Big House or the sadistic overseers in the field. It instead focused on "God and Jesus and the entire pantheon of Old Testament figures who set the standards, established the precedents and defined the values; who, in short, constituted the 'significant others'" (Levine 1977, 37). And, in that regard, the stories of the Bible were a "gold mine" for the slave composers (Lovell 1939, 640).

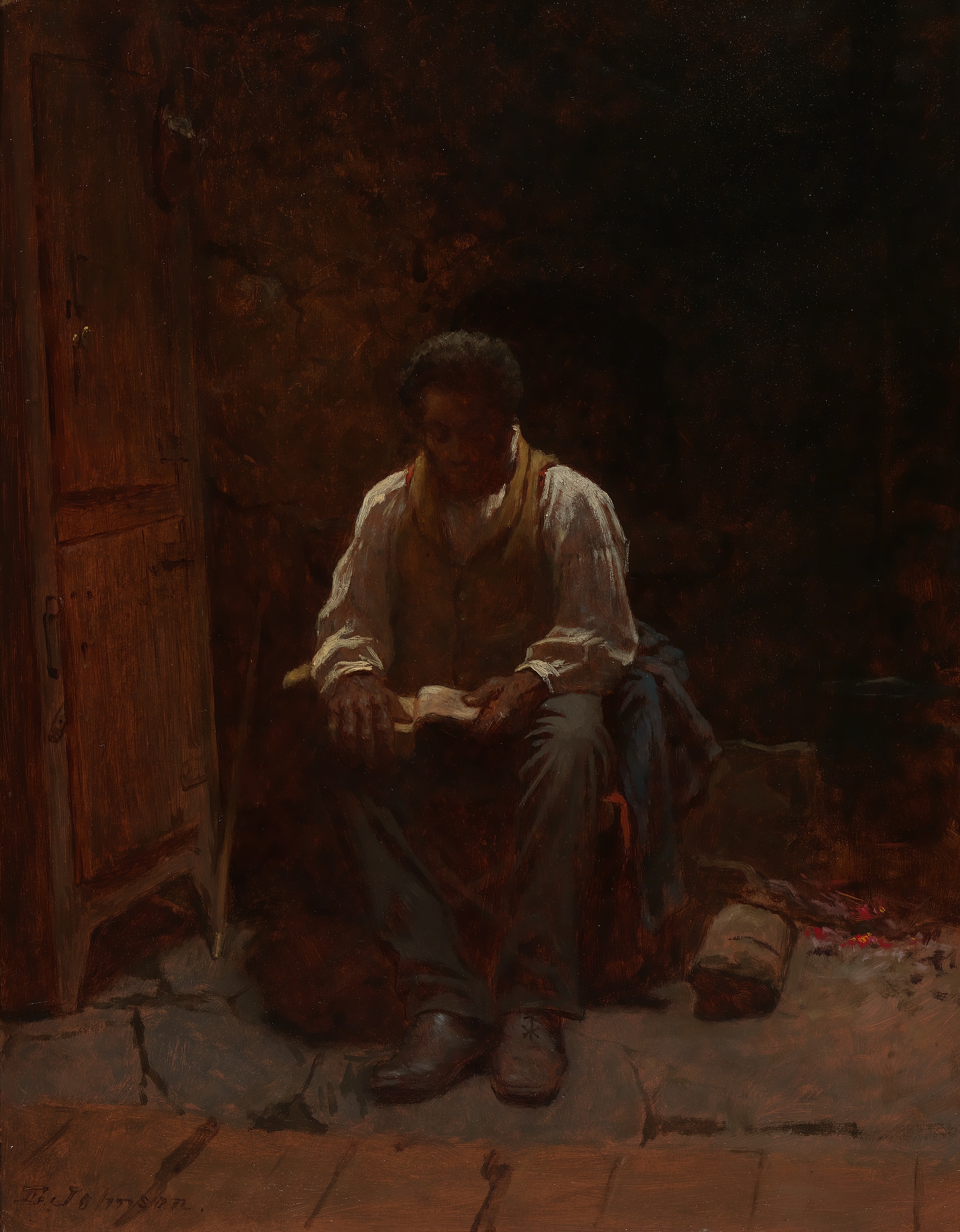

A second reason for the spirituals' enduring power is the absolute, often tender familiarity the slaves enjoyed with the men and women of the Bible. They lived these stories. They sang of King Jesus, Weeping Mary, Brudder Joshua, and the others in the most intimate terms. Even Death is personified:

Spiritual Example 1

Oh Deat', he is a little man

And he goes from do' to do'

He kill some souls and he wounded some

And he lef' some souls to pray

(Levine 1977, 37)

One of the most charming, if a little unsettling, uses of intensely personal imagery in the spirituals depicts a race between the narrator and Satan:

Spiritual Example 2

Ole Satan is a busy ole man

He rolls stones in my way Moss'

Jesus is my bosom friend

He roll 'em out o' my way

(McGee 1960, 47-48)

Booker T. Washington

The plantation songs known as "Spirituals" are the spontaneous outburst of intense religious fervor. They breathe a child-like faith in a personal Father, and glow with the hope that the children of bondage will ultimately pass out of the wilderness of slavery into the land of freedom.

Howard Thurman

For [the slaves] the 'troubled waters' meant the ups and downs, the vicissitudes of life. Within the context of the 'troubled' waters of life there are healing waters, because God is in the midst of the turmoil. Do not shrink from moving confidently out into the choppy seas. Wade in the water, because God is troubling the water.