Listening Guide: Chestnut Brass and Friends "New Bird Waltz"

| "New Bird Waltz" |

||

|---|---|---|

| A | In ¾ time signature opens with the main theme in G major, which consists of eight bars broken down into four distinct sections a + a + b + c (each melodica idea two bars each). | 00:00-00:10] 00:10 |

| B | The opening section comes back with a syncopated melody in the following manner a' + a' + b' + d. | [00:11-00:20] 00:20 |

| C | The opening section-complete sixteen bars-is now repeated. | [00:21-00:40] 00:40 |

| D | Transition section. | [00:40-00:50] 00:50 |

| E | Canary birdcall section in C major. Listen to the "bird whistling," as stated in the score, followed by four bars of-non-birdcalls-to bring this section to a close. | [00:51-01-00] 01:00 |

| F | Canary birdcall section repeated with an additional four-bar extension at the end leading to the key of G major. | [01:01-01:17] 00:17 |

| G | The main themes of the opening section come back before the end of the piece. | [01:18-01:39] 00:22 |

Listening to this work only gives one an idea of how the work must have sounded. Southern confirms this but also goes on to state:

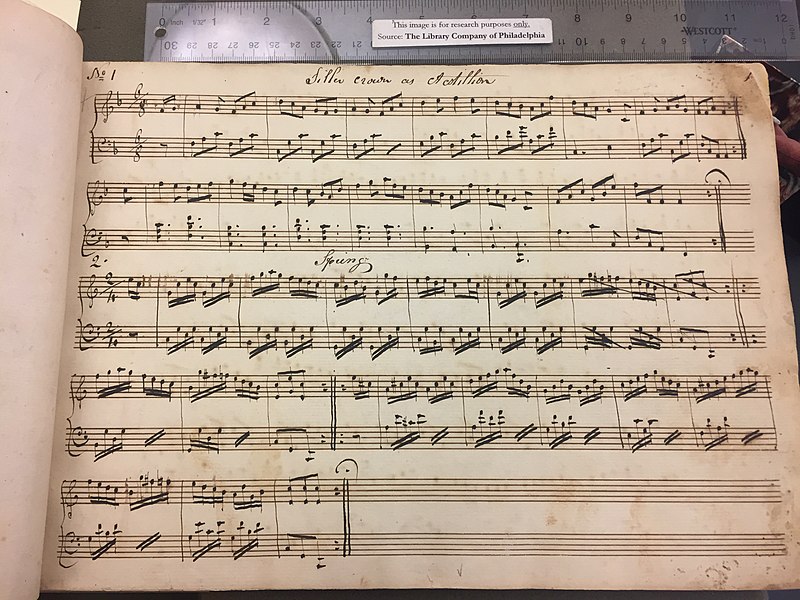

In the first place, we have only piano arrangements of band music or melodic skeletons. This was the common practice of the period; composers left few band or orchestra scores but rather made arrangements that could be sold to the ever-increasing numbers of amateur singers and pianists in the nation. Second, even after Johnson's scores have been reconstructed for performance by instrumental groups, the music hardly seems extraordinary-despite the elaborate flute, violin, and trumpet obbligatos and vocal embellishments-with its predominantly diatonic harmonies, straightforward rhythms, and scalar-triadic melodies. Johnson's style was attuned to the musical climate in which he lived, and his scores do not differ substantially from those of his White American contemporaries-for example, John Hill Hewitt (1801-1890).

(Southern 1997)

In addition, and very important to what Southern states above is her comment on how Johnson stayed ahead of the competition:

Since Johnson competed successfully with White musical organizations for public patronage against the overwhelming odds of race discrimination, his music must have gained something in performance that is not evident in the scores. Based on the admittedly scanty evidence available, that 'something' must have been his ability to 'distort' commonplace music into stimulating and distinctive music. To translate the word distort into modern parlance, we might surmise that it meant infusing the music with rhythmic complexities such as are found in Black folk music or twentieth-century jazz. Thus, Johnson stands at the head of a long line of Black musicians whose performance practice made the essential difference in the transference of musical scores into actual sound.

(Southern 1997, 112-113)