The Birth of Gospel Music 1

The synoptic gospels The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, which describe events from a similar point of view, as contrasted with that of John. of the New Testament provided the genesis of the term "gospel," which according to Christians records the miracles, teachings, saving, and sustaining power of Jesus Christ. Gospel music is the twentieth-century form of African American religious music that evolved in urban cities following the Great Migration of Blacks from the agrarian South around World Wars I and II. During the years 1920-30, an estimated three million Blacks migrated from the rural South to the urban North. Prompted by the desire to establish a better way of life, both socially and economically, this transplanted populace served as a key stimulus for the creation of the form of expression which was to become known as gospel music. The genre gestated in Black churches and became crystalized in the 1930s by former blues pianist Thomas A. Dorsey. With the merging of the elements of blues and the religious fervor of the spiritual, gospel music arose and quickly became the idiom in which the African American community sustained themselves through the theology of "somehow," i.e., something that keeps you up when you are not aware that a superior force is holding you.

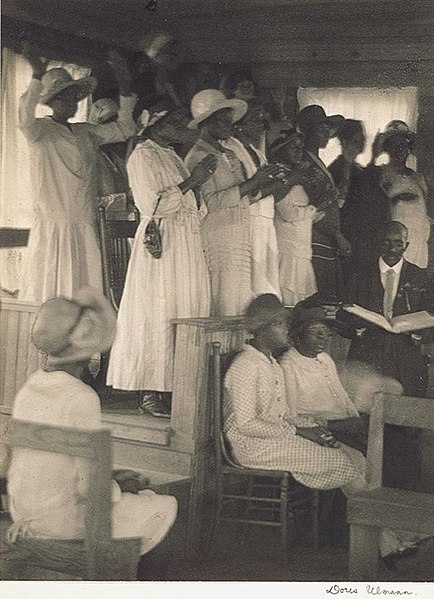

Just as the preaching and worship services of the urban storefront reflected the continuation of a worship style that had distinguished Black independent churches in the rural South, the music expression was also consistent. While the repertoire included Protestant hymns, and occasionally spirituals, most often it was a new genre, sometimes referenced as gospel hymns and other times derisively referred to as jazz hymns, that became the hallmark of these congregations (Drake and Cayton 1962, 622, 670). The use of musical instruments, most of which previously had been associated with secular music and denied entry into the worship of the mainline Baptist and Methodist congregations, was a compelling marker of this new form of religious music expression. A 1929 issue of Crisis magazine, an official publication of the National Association of the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), included this biased, yet noteworthy encounter of storefront worship and its music:

It is night. My errand brings me through a busy street of the Negro section in a city having a colored population of seven thousand. Suddenly I am arrested by bedlam which proceeds from the open transom of a storefront whose show windows are smeared to in transparency. What issues forth is conglomeration itself-a syncopated rhythmic mess of a tune accompanied by strumming guitars and jingling tambourines and frequently punctuated by wild shrieks and stamping feet. Above the din occasionally emerge such words as 'Jesus,' and 'God,' 'Hallelujah,' 'Glory,' and then I realize that this frenzy is being perpetrated in the name of religion. A young man of my own race who has stopped in amazement turns to me half-quizzically and says, 'What do you know about that? Jazzin' God.'

(Crawford 1929, 45)

Given the quote above, it is important to note in the practice of Pentecostal and Holiness churches, who remained closest to the religious experiences of the praise houses, the use of varying instrumentation and body movement (i.e., dance) as integral elements of worship.

Stand By Me

When the storms of life are raging

Stand by me

When the storms of life are raging

Stand by me

When the world is tossing me

Like a ship out on the sea

Thou who rulest wind and water

Stand by me

Leave It There

If the world from you withhold of its silver and its gold,

And you have to get along with meager fare,

Just remember, in His Word, how He feeds the little bird,

Take your burden to the Lord and leave it there.

Leave it there, leave it there,

Take your burden to the Lord and leave it there.

If you trust and never doubt,

He will surely bring you out,

Take your burden to the Lord and leave it there.