Theatre Genres III

Bunraku

During the Kamakura period, wandering blind priests/bards would sing epics, accompanying themselves on the biwa, a predecessor to the shamisen. They sang with great expression, interjecting vocal phrases with biwa. Later, the biwa was replaced by the shamisen. The narrator, or tayu, no longer accompanied himself, but played with a shamisen player. This pairing enabled the singer to focus on two tasks: conveying the deep emotions of the story, and voicing characters.

The instrumentalist, on the other hand, could focus on playing interludes between character vocals. In 1684, when Osakajin singer Takemoto Gidayū (1651-1714) adapted narrative singing to puppet theatre, bunraku was born. To honor his contribution, the tayu/shamisen pair was named gidayū.

Bunraku is an important and popular theatre genre of the Edo period. Like kabuki, which we will cover below, the urban bourgeoisie patronized bunraku. Because bunraku both borrowed from and influenced kabuki, there are significant overlaps between the two genres. Today, bunraku plays are three to twelve acts long. Each act builds over multiple scenes and can last as long as two hours. Bunraku is still performed primarily at the National Puppet Theatre in Osaka and in Tokyo's National Theatre.

The bunraku puppets are exquisite and elaborate. Made of wood, they stand about four feet tall. Three puppeteers dressed in black bring each character to life. The primary puppeteer shows his face, but the other two wear hoods. A puppet can emulate a wide range of human emotions with the exceptionally lifelike movements of its arms, legs, head, and face.

The gidayū, located on stage left, is both an actor and musician. He performs the voices of the puppets and accompanies the narrative with music. The gidayū acts out the feelings and words of all the puppet characters. In order to embody a diverse array of characters, ranging from young to old and virtuous to evil, the narrator must possess great stamina and diversity. Shamisen players and narrators usually team up and work together for years. Because of the tremendous energy required to express the narration, multiple pairs are often used throughout one performance. The vocal style of bunraku, called gidayubushi, includes chanting, dramatic storytelling, character voices, and singing. Like the narrative music from which it stems, the shamisen plays excerpts before, in between, and after the narration. The function of the shamisen is to set a pitch, play interludes, and support the expression of the narrator.

Kabuki

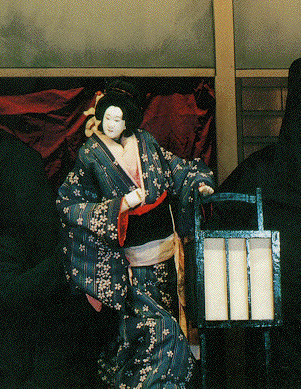

Kabuki is another theatre genre from the Edo period that is still performed today. With lavish sets and costumes, it consists primarily of dance theatre with musical accompaniment. The first kabuki production in 1596 was performed entirely by women. However, after that first performance, the government immediately banned women from kabuki because many of the female actors were also prostitutes. Since 1652, men have performed all roles, both male and female. Onnagata, literally meaning woman-role, are the male kabuki actors who impersonate women.

During the Edo period, the increasingly prosperous middle class preferred kabuki as their main form of entertainment. The genre thus reached new heights of popularity in the 18th and 19th centuries. Performances come to life with lavish sets and costumes, large casts of musicians and actors, flamboyant gestures, and elaborate set changes. Extravagance aside, kabuki borrows many characteristics from its relatively restrained predecessor, noh. The genre also takes plays, acting techniques, and the gidayū from bunraku. Some of Japan's most famous theater pieces are performed in both bunraku and kabuki.

Kabuki uses revolving platforms, trap doors, and a long runway, or hanamichi, that goes through the audience connecting the stage to the rear of the theatre. Trap lifts bring scenes or musicians up to the stage, and the revolving platforms allow quick changes from one opulent scene to the next. The hanamichi is an integral part of the stage because it allows the actors to interact more intimately with the audience.

The musical makeup of kabuki clearly indicates noh and bunraku influence. In addition to the gidayu, three fairly independent ensembles play during a kabuki performance. They are the debayashi, the shitakata, the and the geza.

The debayashi consists of four to eight shamisen players and a male chorus. With beautifully choreographed movements, they appear on a platform at the back of the stage and kneel throughout the performance.

The shitakata also sits on the stage, positioned in front of but beneath the debayashi. This group consists of the noh hayashi ensemble-a nohkan, o-tsuzumi, ko-tsuzumi, and taiko.

The geza ensemble, which provides sound effects, is always off stage. Its numerous instruments include idiophones (e.g., clappers, cymbals and gongs), shamisen, o-daiko,nohkan, and any other instruments required by a particular play. The stage manager plays the hyoshigi, a set of rectangular woodblocks, to signal the beginning as well as the end of the play. The narrator, or chobo, and a shamisen player derive from Bunraku gidayū. Up to four chobo may perform together; they narrate the story, explain the plot, and comment to the audience on the play's action.

Today, the Kabukiza is the theatre dedicated to kabuki. Built in 1887 and located in Tokyo, it performs two programs a day: one from 11 am to 4 pm, and another from 4:30 pm to 9:00 pm. Each program consists of a few plays separated by brief interludes during which people eat and shop in the lobby area.

Although Bon is a religious festival in Japan, most Bon dancing songs are now secular in nature.