Pinkster Celebrations

Another important celebration at the heart of slave culture in the eighteenth century was Pinkster, which took place primarily in New York and New Jersey. "Initially Pinkster had been a Dutch holiday-Pentecost-that occurred seven weeks after Easter, in late May or early June, at about the same time of year as the New England Election Day. Throughout most of the eighteenth century, Pinkster was probably a low-key event in which both the Dutch and their slaves took part…. After the Revolution, however, Pinkster became associated closely with African Americans" (White 1994, 18). This holiday celebration took place in Long Island, New York, and New Jersey, the locations of Dutch settlement. "It was in Albany in the 1790s and the first decade of the nineteenth century that Pinkster reached its apogee.

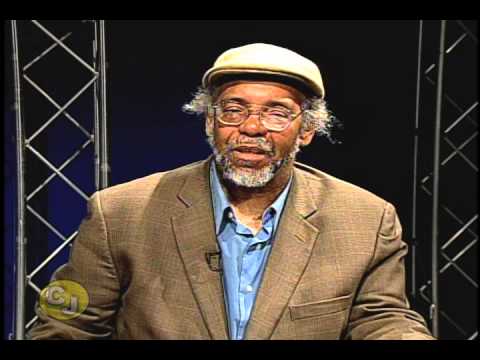

Here the enslaved African known as King Charles-who allegedly was from a royal and princely lineage in Angola (who, unlike the African American kings and governors of New England, was not elected) presided over the week-long festivities on Pinkster Hill" (White 1994, 18). According to Southern, the "earliest reference to the popular name of the holiday occurred in a Sermon Book of 1667 by Adrian Fischer, "Story of the descent of the Holy Ghost on the Apostles on Pinkster Dagh'" (Southern 1997, 53). Watch this video on Pinkster Celebration.

Pinkster Celebration with Dr. John Norvell [ 00:00-00:00 ]

White observers of this day of celebratory activity mention that the characteristics that stand out surround the "extravagant style of the African American participants…. It was a time for excess, for release from the rigors of a northern winter and the everyday exigencies of a slave regime, and the exuberance exhibited by the slaves-in their clothing, feasting, music, and dance-made the African American participant seem larger than life" (White 1994, 21). White's narrative concerning the music is presented here in its entirety:

Through their music and dancing, more than through the structure of the festivals, northern slaves conclusively revealed their distinctive culture. Music was provided by the fiddle, ubiquitous in eighteenth-century African American life, the Jew's harp, the banjo, drums, and even fish horns. The Guinea drum used at Pinkster was made from a log, four feet long, about fourteen inches in diameter, burnt out at one end, and covered with a tightly drawn sheepskin. On this, an anonymous spectator observed disdainfully, the musician "thump[ed] with his fist a king of barbarous ill composed or uncomposed air," accompanied by a "hoggish sort of grunting, a bawling and mumbling." The improvisatory nature of the slaves' music, their willingness to incorporate what Europeans considered novel sounds, was neatly suggested by the fact that in New York whistling was called "Negro Pinckster Music" long after the festival itself had died. As the slaves were caught up in the performance, their behavior became more African…. [They] were granted unusual liberty to enjoy themselves according to their own ideas, which had clearly been carried across the Atlantic Ocean from Africa.

(White 1994, 23)

Go Down, Moses

Dark and thorny is de pathway

Where de pilgrim makes his ways;

But beyond dis vale of sorrow

Lie de fields of endless days.

Booker T. Washington

The plantation songs known as "Spirituals" are the spontaneous outburst of intense religious fervor. They breathe a child-like faith in a personal Father, and glow with the hope that the children of bondage will ultimately pass out of the wilderness of slavery into the land of freedom.