The ASCAP Ban

The American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) is a not-for-profit performance rights organization (PRO) that protects its members' musical copyrights by monitoring their music's public performances, whether via a broadcast or live performance, and compensating them accordingly. ASCAP collects licensing fees from users of music created by ASCAP members, then distributes them back to its members as royalties. In effect, the arrangement is the product of a compromise: when a song is played, the user does not have to pay the copyright holder directly, nor does the music creator have to bill a radio station for use of a song. Radio's ban on ASCAP music had a positive, though unintended, effect on the air time of songs by regionally and ethnically diverse musicians.

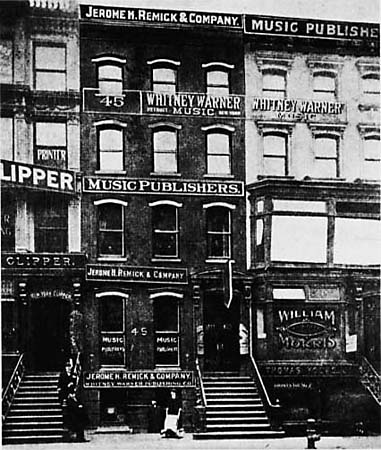

ASCAP was founded in New York City on February 13, 1914, to protect the copyrighted musical compositions and collect fees for its members, who were mostly writers and publishers associated with New York City's Tin Pan Alley. When radio came along, the organization began charging stations for the right to use the songs, and the corresponding fees kept escalating. Radio stations had joined together in 1923 to start an advocacy group, the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB), whose initial aim was to fight ASCAP's fees. But ASCAP continued to charge more, and radio continued to protest, culminating in 1940 with banning all ASCAP material from the airwaves (see Ryan 1985). While the legal dispute lasted, U.S. radio exposed their listeners to a diet of out-of-copyright or traditional songs. These included songs from regional or ethnically based publishers that ASCAP had not admitted as members. Radio networks increasingly licensed those works through their newly established licensing agency, Broadcast Music Inc. (BMI). Thus, audiences became exposed to a greater variety of musical styles than ever before, particularly country music and rhythm and blues. As Malone (1985) concludes, "BMI was instrumental ... in breaking New York's, or Tin Pan Alley's, monopoly on song writing. The American music industry consequently became more decentralized. Songwriters were encouraged all over the United States, and producers of the so-called grassroots material (country and race music) were given a decided boost" (Malone 1985, 179). The impact of this copyright dispute on the history of popular music cannot be underestimated. BMI proved a major contributing factor to the rise of rock and roll in the 1950s (Whitcomb 1972; Barnard 1989).

Likewise, although Blacks in the southern part of the United States were starting to acquire radio receivers in large numbers early in the 1940s, there were no African American music shows on the air. "King Biscuit Time" was one of the first and most influential live radio programs aimed at Black listeners.

King Biscuit Time - More Broadcasts Than Any Other Radio Show [ 00:00-00:00 ]

In closing this section, ASCAP, BMI, FM radio, rhythm & blues, rock & roll, and teenagers buying power, all contributed to the dissemination of African American music, and consequently Black culture.

Elvis Presley's "Hound Dog"

The lyrics are about the animal "hound dog" and how it's no friend of Presley's because he's often crying, is not high class, and has never caught a rabbit.

Big Mama Thornton's "Hound Dog"

The lyrics are metaphorically about a "man," Although she refers to him as a hound dog, with lines such as "Daddy I know, you ain't no real cool cat" and "you ain't lookin' for a woman, all you're lookin' for is a home" she is speaking about a man.