Music in Pre-Columbian Peru

Archaeological evidence suggests that music was already developed in pre-Columbian Peru thousands of years before the arrival of the Spanish invaders in the Andean area. Numerous instruments found in the tombs and ruins of ancient cities strongly suggest that music was an important part of many ancient cultures, particularly in religious ceremonies. They appear to have been played to accompany priest processions, to signify the high point of certain ceremonies, or to complement sacrificial rites intended to sooth and please the gods or ban evil spirits. The evidence also indicates that people played music in their homes for entertainment or as part of domestic rituals, and that it was also an integral part of processions, feasts, festivals, and staged ceremonies involving large congregations. In summary, music appears to have been an essential part of daily life and at the center of important social activities of ancient pre-Columbian Peruvian cultures

Instruments excavated from pre-historic ruins belong exclusively to the woodwind or percussion families. They include the antara (panpipes), flautas (flutes), pitos (whistles), sonajas (rattles), panderetas (tambourines), campanas (bells), and trompetas (trumpets), including the waqra phuku (Quechua waqra horn), a trumpet used in fertility rituals and usually made of cattle horn. Many indigenous instruments of ancient Peru had symbolic and social meanings. Depending on environmental, social, or religious circumstances, instruments could be made from different materials such as cane, animal horns, bone, metal, pottery, shell, and wood. Flutes, for instance, were often made of bird bones since birds, which appeared to fly from heaven to earth, were considered sacred.

Amerindians (native indians) inhabited Peruvian territory for thousands of years before the Spanish Conquest of the Inca Empire in the 16th century. In fact, between the fourth and second millennia BC, Peru was home to the Caral or Norte Chico civilization-the oldest civilization in the Americas-and later, to other cultures including the Chavin, Nazca, Moche, Sican, and eventually the Inca Empire, the largest and most sophisticated state in pre-Columbian America, which arose from the highlands of Peru in the early 13th century and lasted until 1572. Let's take a brief look at the music manifestations in each one of them.

Norte Chico (Caral) Civilization

Sometime around 3,000 BC[1]Eurekalert.org, "Oldest evidence of city life in the Americas reported in Science, early urban planners emerge as power players" Public release date: 26-Apr-2001 American Association for the Advancement of Science. -around the same time that Egypt's great pyramids were being built-there was the Sacred City of Caral, the most ancient city of the Americas, and home to the roughly 3,000 people of the Caral or Norte Chico civilization-one of the six cradles of civilization in the world (the other five being Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, China, and Mesoamerica).[2]Mann, Charles C. (2006) [2005]. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Vintage Books. pp. 199-212. ISBN 1-4000-3205-9. One of the largest and best studied archaeological sites in South America, this area was once a thriving human settlement with an elaborate complex of monumental temples, an amphitheatre, and ordinary houses spread out over 150 hectares (370 acres) in the Supe Valley on the north-central coast of present-day Peru.

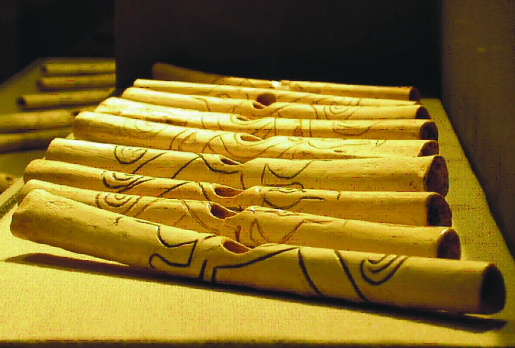

While visual arts appear absent in the ruins of Caral, it is quite evident that its people played instrumental music. The Peruvian archaeologist Ruth Martha Shady[3]Shady, R. Haas, J. Creamer, W. (2001). Dating Caral, a Pre-ceramic Site in the Supe Valley on the Central Coast of Peru. Science. 292:723-726. doi:10.1126/science.1059519 PMID 11326098 ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. of the University of San Marcos in Lima, discovered sunken circular plazas suitable for mass public assemblies, shrines with ceremonial fire pits, and caches of offerings. Among the many significant objects found in the circular plaza of the 'Amphitheater Pyramid'-one of six large Caral pyramidal structures where hundreds of people could congregate for community events-she discovered 32 tubular horizontal flutes made of condor and pelican bones, and 37 cornets made of deer and llama bones dating to around 2,200 BC.[4]Shady Solís, Ruth Martha (1997). La ciudad sagrada de Caral-Supe en los albores de la civilización en el Perú (in Spanish). Lima: UNMSM, Fondo Editorial. Retrieved 2007-03-03. Mann, Charles C. (2006) [2005]. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Vintage Books. pp. 199-212. ISBN 1-4000-3205-9. Miller, Kenneth (September 2005). "Showdown at the O.K. Caral". Discover. 26 (9). Retrieved 2009-10-22.(Wikipedia - Norte Chico civilization)

The flutes, most of which were decorated with engravings representing stylized monkeys, snakes, birds, and anthropomorphic figures, could produce seven different sounds by blowing into the central hole and covering either the left or right-hand holes. These discoveries at Caral strongly suggest that music was an integral part of the ritual life of Andean people 5,000 years ago.

The Caral culture (roughly 30th century BC to 18th century BC), the predecesor of the Chavin de Huantar civilization and to the Inca Empire that emerged 4,400 years later, appears to have been a peaceful civilization whose people spent considerable time studying the heavens, practicing their religion, and playing musical instruments.

Caral was mysteriously abandoned after only 500 years, but the cultural, technological, religious, and social influence of its extraordinary inhabitants is evident in most of the civilizations that followed them over the next 4000 years.

Chavin Civilization

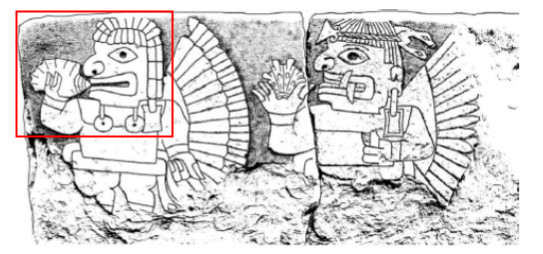

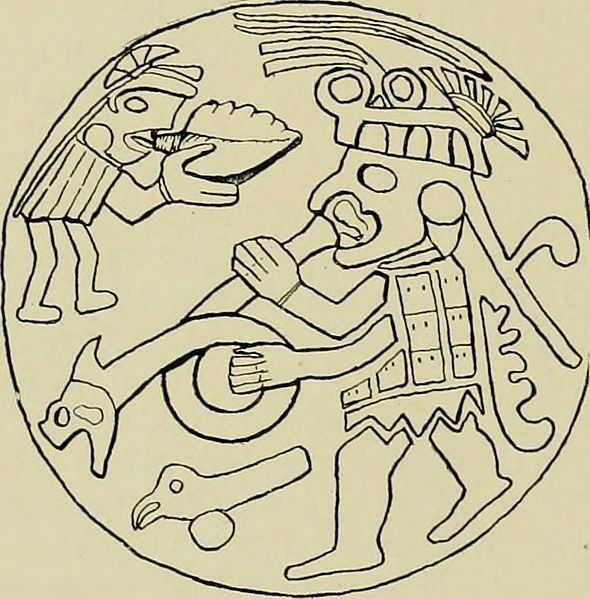

Music also played an important role in the religious rituals of the Chavin people. Strombus shell trumpets, such as the ones shown here, have been found at Chavin sites.[5]Contreras, Daniel A. (2017). Rituals of the Past: Prehispanic and Colonial Case Studies in Andean Archaeology. University of Colorado. pp. 51-77. They appear to have been stored underground and used by ritual practitioners in processions similar to the one pictured below through the underground galleries of their settlements.[6]Weismantle, Mary (2013). Making Senses of the Past : Toward a Sensory Archaeology. Southern Illinois University Press. pp. 113-133.

Evidence of music in rituals is abundant in sites dating between 1000 and 200 BC., and later. At the ceremonial center of Chavín de Huántar, engraved stone slabs surrounding a sunken circular court show elaborately dressed figures walking in procession and carrying ritual objects such as spondylus shells, hallucinogenic cactus stalks, and shell trumpets (see figure inside the red rectangle).

The discovery of twenty worn-out shell trumpets (pututos) are a strong indication that these instruments were actually used in the ceremonies of Chavín de Huántar. The trumpets are made with strombus shells most likely obtained through long-distance commerce with coastal cultures. Some highly polished shells are occasionally engraved with complex designs. Notice how the strombus shell trumpet pictured above (right) is cut at the extremity to form the mouthpiece.

Nazca Culture

Shell trumpets were not the only musical instruments associated with processions in Andean cultures. In the Ica and Nasca valleys of the Peruvian south coast, between 100 BC and 700 CE, the Nazca people, arguably the most important pre-Columbian musicians, used ceramic drums, whistles, trumpets, and panpipes in ritual contexts.

Nazca antaras (panpipes) were made of a single row of three to fifteen vertical, tubular pipes made out of reeds or fired clay, such as the one pictured here. According to scholars-chief among them Mariano Béjar Pacheco, Jorge C. Muelle, Carlos Vega, and André Sas-the Nazca antaras were capable of producing diatonic, chromatic, and even microtonal music with a precise tuning, much like the Western European scales supposedly 'discovered' many centuries later.

Major Nazca rituals were associated with planting and harvesting, preparation for war, and with the primary rites of passage such as birth, adolescence, marriage, and death. Nazca art was very sparing in its depiction of everyday life, unlike the contemporary Moche whose art is replete with such details. Direct archaeological evidence for these activities is, therefore, minimal. On a few choice vessels there are groups of farmers drinking and rejoicing at harvest time, accompanied by music played from antaras.

Nazca ceramic drums often represented anthropomorphic figures with a bulbous body forming the sounding chamber of the instrument. The mouth of the drum, which was once covered by a stretched skin, is located under the figure that had to be placed upside down or sideways in order to play. Archaeological investigations suggest that Nazca musical instruments were important ritual objects used during group performances at the ceremonial center of Cahuachi, the most important sacred site of the Nazca civilization. They were also likely played during processions along the great Nazca geoglyphs (Nazca lines), which were probably used as ritual pathways.

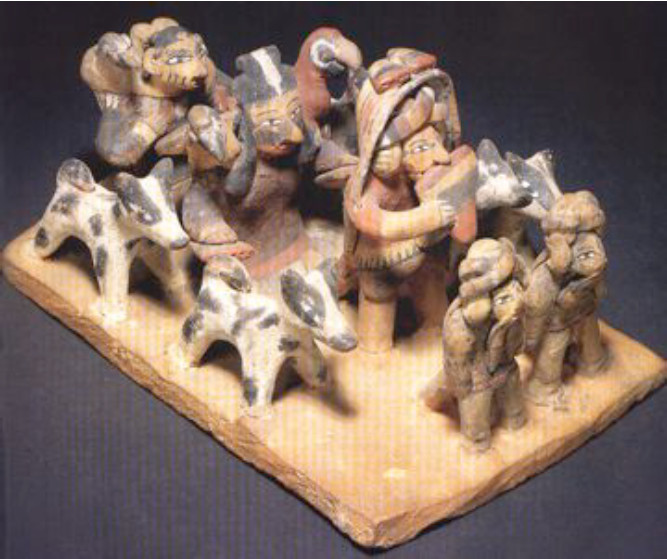

One such procession is depicted (left) in a unique modeled scene that portrays a procession or pilgrimage. In it, a group of people, perhaps a family, is aligned as if marching. The figure in front (the older male) is playing the pan pipes, while the female figure behind him (maybe the mother in the family) is holding two more. The marchers may be traveling to Cahuachi, a major ceremonial center of the Nazca culture, to make offerings (Silverman 1993).[7]Cahuachi in the Ancient Nasca World. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. This artifact suggests the important role that pilgrimage and music may have had in ancient Nazca religion.[8]Proulx, Donald A. (2007). The Nasca Culture: An Introduction. University of Massachusetts. Proulx, Donald A. 2007 Nasca Ceramic Iconography: An Overview. University of Massachusetts. In fact, one of the most well-known constructions at Cahuachi is the "Room of the Posts," which is characterized by adobe walls painted with images related to Nazca ceremonial artifacts, such as Nazca panpipes (Silverman 1987).

Moche Culture

The Moche people (also known as Mochica), who flourished on the north coast of Peru between 100 and 900 AD, used ceramic trumpets, such as the one shown here, going back to AD 300.

The National Museum of Archeology, Anthropology, and History of Peru, located in Lima, houses approximately 2,000 pre-columbian musical instruments that date between 4,500 and 5,000 years BC. Other important collections are housed at the Museo Larco, also in Lima, and the collection from the San Jose de Moro Archaeological Project at Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Peru (PUCP).

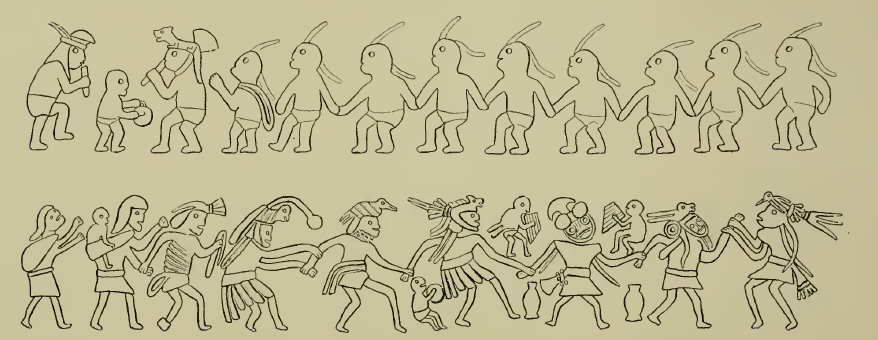

Musical instruments were also an integral part of ritual processions in the Moche culture. Moche ceramic imagery shows musicians, human priests, and warriors as well as skeletal individuals walking in line or dancing while playing panpipes, flutes, rattlepoles, trumpets, drums, and pututos sometimes made out of marine shells. An estimated 80,000 to 100,000 Moche vessels have found their way into museums and private collections worldwide (Weismantel 2004). Depictions of musical instruments and musicians on these artifacts firmly shows the importance of music in Moche rituals and social relations.

There is a strong connection between music and death in Moche iconography. Diverse instruments appear in a great variety of scenes related to death and the afterlife such as macabre dances, funerary processions, and erotic scenes involving skeletons. Moche whistles, such as the one shown here, have been discovered in funerary contexts related to human children sacrifice. Many familiar objects included rattles that made sounds when used.

Sicán (Lambayeque) and Chimú Cultures

Two cultures arose in the north coast of Peru after the decline of the Moche civilization: The Sicán, or Lambayeque located in what is now the north coast of Peru (750 to 1375 CE), and the Chimú (1150-1470) in the Moche Valley. The Chimú conquered the Sicán around 1375, and were, in turn, conquered by the Inca around 1470.

The Chimú represented musicians through vessels and delicate miniature sculptures made with joined silver sheets or wood inlaid with shell pieces. These pieces represented multiple characters carrying mummy bundles or offerings, serving or drinking corn beer, and sometimes musicians playing drums, rattles, flutes, or panpipes, like the one pictured here. Whistling vessels equipped with a mechanism produces sound when the liquid inside the bottle is poured out were also made by the Sicán and Chimú people.

The Incas

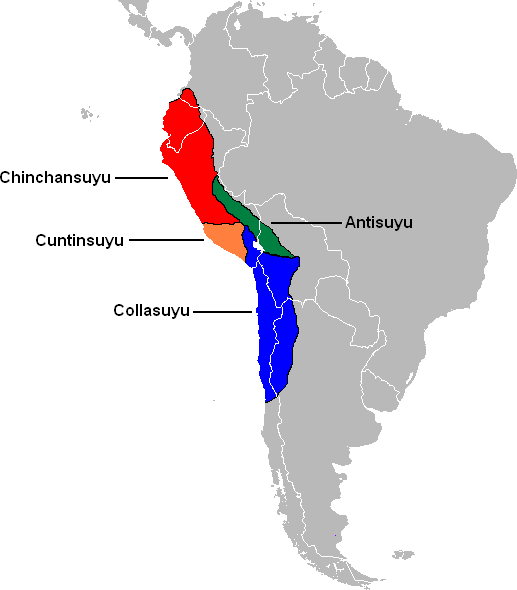

The great Inca Empire stretched from modern-day southwest Colombia to central Chile, an area of over 3 million kilometers, with more than 5,000 kilometers (3,107 miles) of Pacific ocean coastline, representing double the territory of present-day Peru.

This was the Tahuantinsuyo of the Inca, the ruling tribe which brought together many of the most ancient cultures in the region, including Chavin, Paracas, Moche, Chimú, Nazca, and twenty other minor ones. The word Tahuantinsuyo is formed from two quechua words: Tawa, meaning four, and suyo meaning state.[9]McEwan, Gordon F. (26 August 2008). The Incas: New Perspectives. W. W. Norton, Incorporated. pp. 221-. ISBN 978-0-393-33301-5. The Inca Empire was, therefore, made up of four regions: The Chinchansuyu (north), which encompassed the former lands of the Chimú Empire and much of the northern Andes; the Cuntinsuyu (west), which included the Nazca area; the Collasuyu (southwest), the largest of the fours suyus going almost as far down as modern Santiago de Chile; and the Antisuyu region (east), which bordered on the modern-day upper Amazon region.

Inca musicians inherited a tradition stretching thousands of years. Like their predecessors, they used music in cooperative ways in a wide variety of social, military, religious, and everyday occasions, such as to communicate with the ancestors, heal the sick, and bury the dead. Music infused every aspect of life: War and pilgrimages-perhaps providing them with a sense of supernatural power-community festivals, and rituals associated with agricultural activities and fertility rites.

For the Incas, music, dance, and song weren't separate activities, but an interconnected whole designated with the Quechua word taki (sometimes spelled 'taqui').[10]Teresa Vergara, Historia del Perú , curated by Teodoro Hampe Martínez, Incanato y conquest, Barcelona, Lexus, 2000, ISBN 9972-625-35-4. Their music consisted of religious chants, love songs, and a wide variety of dance melodies for instrument and voice (Tschopik, 1964).[11]Harry Tschopik, FOLKWAYS ETHNIC LIBRARY Album No. FE 4415 © 1949, 1961 by Folkways Records & Service Corp., 43 W. 61st St., NYC, USA 10023 Peruvian Inca Wind Instruments Dale Olsen, Music of El Dorado, pp. 17-22. Within a century of the Spanish invasion of 1532, the mestizo historian Garcilaso de la Vega (1539-1616)-the natural son of a Spanish colonial official and an Inca noblewoman born in the early years of the conquest-mentions in his Comentarios Reales de los Incas (Lisbon, 1609) that each song text had its own unique melody.

The Incas appear to have used any and all kinds of materials (animal, mineral, and vegetable) for the construction of their musical instruments-stone, wood, animal bones and horns, clay, reeds, metals, seashells, and gourds were all adapted to musical use.

With those materials, they produced a wide variety of instruments, including:

- Wind instruments (aerophones): Such as antaras, the quena, and trumpets such as conch trumpets (instruments of war due to their penetrating and awe-inspiring blasts), the waqrapuku, made of cow horns brought by the Spanish, and guayllaquepas, inherited from the Moche culture.

- Drums (membranophones): Including the tinya-a small drum made with goatskin heads and a cylindrical body constructed of eucalyptus bark, usually played by women-and the huancar or wankara-a large drum used by males in ritual, ceremonial, and war situations.

- Noise-making rattles (idiophones).

How do we know about these instruments today? Much of our understanding comes from the study of images from the pre-Columbian period that depict their use in various settings. Numerous pottery vessels decorated with figures (see above) in the act of dancing, beating drums, and playing some of those instruments have been found with mummies in ancient graves.[12]Mead, Charles. The Musical Instruments of the Incas. American Museum Journal, Vol III, No. 4, July 1903. We also have written accounts, often by Christian missionaries, some of whom recorded in musical notation the indigenous melodies they heard. Also, some indigenous populations have preserved their musical traditions long after the conquest through oral transmission.

Although it is difficult to know how the instruments really sounded or what techniques were used to play them, and because some of those instruments appear to be almost identical with those in use in many parts of Peru to this day, sound recordings collected by musicological field studies may help us come close to the aural image of how they might have sounded thousands of years ago.

The tinya is used nowadays in traditional dances, as in the following Wakrapukara-a Quechua dance from the Cuszo region said to be a survivor of a war dance-where it keeps the beat to the melody played by the quena.[13]Kike Pinto Cárdenas - El Waqra Phuku.

Composer: Anonymous

-

"Wakrapukara"

In the following herranza, we can hear the waqrapuku-also called cow horn-and the tynia. This selection is associated with the livestock ceremony where a herd owner holds a reception in honor of his animals, and the entire family is invited to put ribbons in the ears of each herd animal. Coiled trumpets made from cow horns are common. A modern version of this type of trumpet, complete with conical bell at one end and a conventional modern mouthpiece at the other, is made from sheet metal cylinders.

Composer: Anonymous

-

"Herranza"

The following music selection features men of Pisac, a small town north of the city of Cuzco, playing conch shells.

Composer: Anonymous

-

"Conch Shells"

String instruments did not exist in the Peru region prior to the Spanish conquest