Studying Native North America

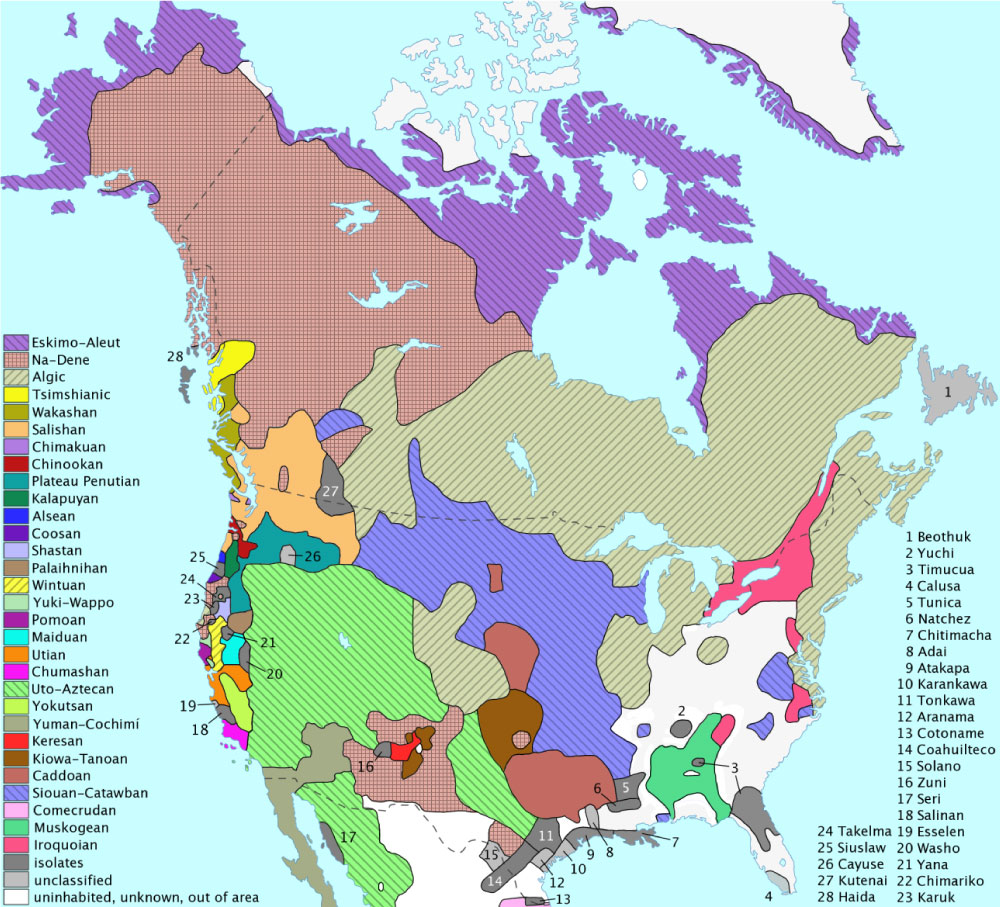

Before the arrival of Europeans, native North Americans did not think of themselves as a single racial or ethnic group. Native peoples spoke many different languages and had ways of life adapted to their environment, whether it was in the Arctic Circle or the desert Southwest.

Even when Europeans began to arrive on the shores of eastern North America, the native tribes and confederacies in many cases saw them simply as a different tribal group-perhaps one that could be traded with or serve as allies-and it was not until the late 1700s that a sense of "Indian" ethnic identity began to develop.

Although contemporary native people identify themselves often more generically as "Indians" or "natives," traditional music associated with specific tribes has in most ways stayed unchanged for centuries, making it difficult to discuss North America as a single unified musical region, and necessitating the continent be divided into multiple geographic areas in order to study the music, for example as the Northeast, Southwest, Pacific Northwest, and Great Plains. These regions are known as "culture areas," and music from one area is often compared and contrasted with music from another as part of learning to understand how music works in a given context.

One reason we know that many types of Indian music have remained unchanged is that beginning in the 1880s, ethnologists (researchers who study culture) began fanning out across North America, making recordings and documenting musical performance and dance traditions. Probably the most famous of these was Frances Densmore (1867-1957), who spent more than forty years crisscrossing North America with her wax cylinder recording machine in tow, interviewing and recording elderly singers. Densmore's recordings are now an invaluable resource for researchers and tribal members alike.

In Native American cultures, the roles of music and dance are connected with ceremonial rituals.