The Colonial Period

With the conquest and subsequent colonial era, Peru inevitably received the influence of European music and later, the Afro-Peruvian population. The most notable consequence of that influence was the introduction of Spanish stringed instruments during the Sixteenth Century. Of these the most significant were the harp, with a diatonic scale through five octaves, and the mandolin, which, modified by the Indians and reduced in size, became the charango of the contemporary Quechua and Aymara. At a later date also the guitar and violin were introduced, but were accepted more widely among the Mestizos. In spite of these modifications, however, the ancient pentatonic scale, practically unknown in Spain, has continued in use among the Indians of the southern Peruvian highlands.

We are not completely sure how Europeans felt about the indigenous music they encountered. Much of it included religious chants, love songs, and various dance melodies. We do know, however, that in the interest of christianizing the Indians, Spaniards did their best to suppress Inca music and dances, because of their close association with native religious practices (Tschopik, 1964). One seventeenth-century Jesuit priest proudly claimed to have personally destroyed 4,023 drums and flutes in Peru; in Lima, the capital of the viceroyalty of Peru, natives who owned these "pagan" objects could receive three hundred lashes. Other religious leaders, however, were opposed to such maltreatment. Although intent on converting the indigenous peoples to Christianity, they tried to make them give up their gods and rituals through non-violent means. The missionaries taught singing, music theory, and instrument building to the natives, and composed hymns for Christian religious services based on familiar native melodies. They also composed new hymns in indigenous languages.

Over the centuries, many indigenous peoples of South America have resented the attempt by European colonial powers to expunge their languages, music, and religious practices. Some indigenous populations did not survive the conquest and were eradicated through wide-scale massacres or forced hard labor. Others died from previously unknown diseases to which they had no natural immunity; smallpox was one of many such diseases carried by the European invaders. Today, many indigenous people live in dire poverty. We should keep these realities in mind as we examine those indigenous musical influences that have endured, in different forms, into modern times.

Let's return to sixteenth-century Peru, specifically to the Inca capital of Cuzco, where splendid religious festivals involving up to one hundred native musicians took place. In 1533, Pizarro and his men entered the city. If you were a member of his party, you might have witnessed the execution of the Inca chieftain Atahualpa, who defied both the Catholic Church and the invaders ("conquistadores" or conquerors), and the building of churches and convents that replaced the Incan temples.

One such building was the Cuzco cathedral, built on the ruins of an Incan palace. Begun in 1560, it took over one hundred years to be completed. Naturally, a great deal of music was performed in cathedrals and churches. Even though Christian missionaries used music to impose their religious views on the indigenous people, the fact remains that music of the Catholic rite can be exceptionally beautiful at times. It tends to be elaborate, often weaving together several independent parts in a texture known as polyphony. At this point in history, the mass would have been sung by a trained choir rather than the congregation.

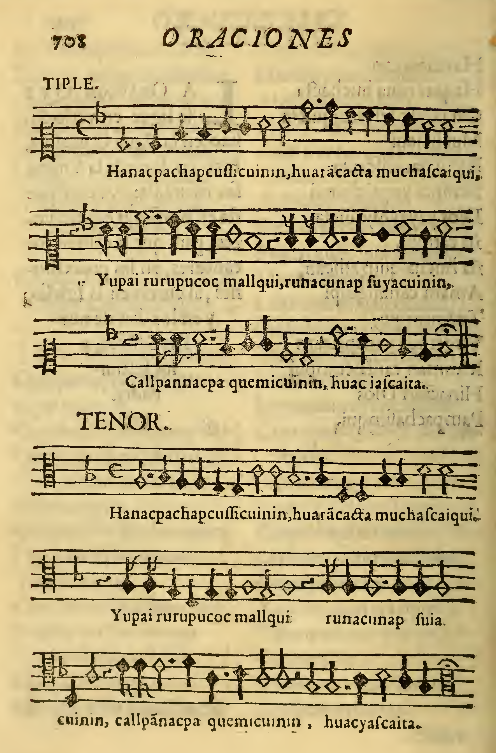

In 1631, at the Andahuaylilas Church, Juan Pérez Bocanegra (1598-1631), a Franciscan priest, musician, and specialist in the indigenous languages of colonial Peru, compiled a book called the Ritual formulario e instituciones de Curas.

The book describes Incan social structures and customs, knowledge of which, it was believed, would enable the priests to ingratiate themselves with the natives. The Ritual formulario gave texts to various rituals in both Quechua and Spanish. It is particularly noted for Hanacpachap cussicuinin, the earliest polyphonic vocal work printed in the New World, a hymn to the Virgin Mary in Quechua likening her to the Pleiades, a constelation well-known to the Incas. It is unknown whether the hymn was composed by Bocanegra or a local indigenous person.

Composer: Juan Perez Bocanegra

-

"Hanacpachap Cussicuinin"

Hanaq pachap kusikuynin Waranqakta much'asqayki Yupay ruru puquq mallki Runakunap suyakuynin Kallpannaqpa q'imikuynin Waqyasqayta.

Heaven's joy! a thousand times shall we praise you. O tree bearing thrice-blessed fruit, O hope of humankind, helper of the weak. hear our prayer!

Composer: Juan Perez Bocanegra

-

"Hanacpachap Cussicuinin" [ 00:00-00:05 ]00:05

Uyariway much'asqayta Diospa rampan Diospa maman Yuraq tuqtu hamanq'ayman Yupasqalla, qullpasqayta Wawaykiman suyusqayta Rikuchillay.

Attend to our pleas, O column of ivory, Mother of God! Beautiful iris, yellow and white, receive this song we offer you; come to our assistance, show us the Fruit of your womb!

Composer: Juan Perez Bocanegra

-

"Hanacpachap Cussicuinin" [ 00:05-01:25 ]01:19

Lima had its cathedrals and churches as well. At the Lima cathedral, one director of music (maestro de capilla) was Tomás de Torrejón y Velasco, a Spaniard who came to the New World in 1667 when his royal patron was named viceroy of Peru. He must have been extremely versatile: once in Peru, he supervised the armory and was a magistrate in addition to writing music for the Catholic liturgy. Torrejón y Velasco also composed the first opera ever performed in the New World. La púrpura de la rosa (The Blood of the Rose), whose story is based on classical mythology, premiered in Lima in 1701. Torrejón y Velasco was so famous that some of his music was known as far away as Guatemala.

Opera, of course, was a European invention and any opera by a Latin American composer during the eighteenth century was European in outlook in that indigenous music played no role. This was also true of practically all concert music composed in Peru well into the nineteenth century; indeed, throughout the New World, upper-class families considered familiarity with European music a mark of refinement. Still, in 1875 the Italian immigrant composer Carlo Enrico Pasta wrote an opera called Atahualpa, after the vanquished Incan leader.

Other Peruvian composers, such as José María Valle Riestra (1858-1925), not only wrote in the European style, but were actually trained in Europe. By the early twentieth century, however, some composers began to challenge the powerful influence of European music. They felt that one way to write music more authentically of the New World was to return to the indigenous heritage. Daniel Alomía Robles (1871-1942), whose works incorporated Quechua melodies and rhythms, was notable among South American composers who followed that line of thought.

'Anti' is the likely origin of the word 'Andes', Spanish conquerors generalized the term and named all the mountain chain as 'Andes', instead of only the eastern region, as it was the case in Inca era.