Introduction

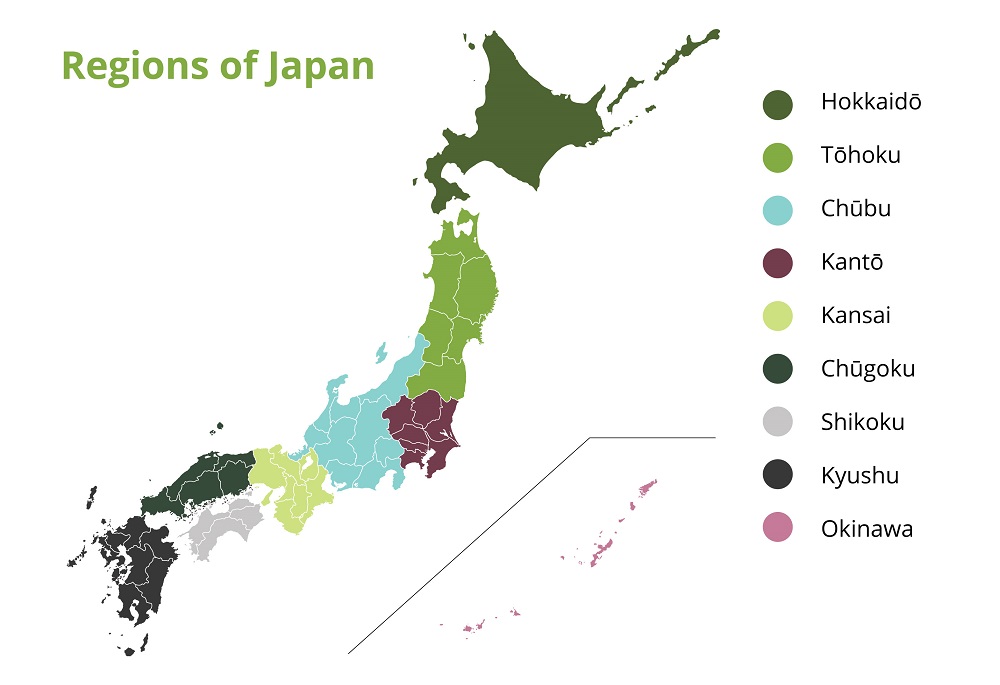

Japan, a spectacular archipelago nation located in East Asia on the Pacific Ocean, consists of four primary islands and thousands of smaller islands. The four main islands, which together comprise ninety percent of the country's land area, are: Honshu; the mainland Hokkaido in the far north; Kyushu in the far south; and the smallest, Shikoku, in the southeast.

Japan's landmass measures roughly 150 thousand square miles, which is equivalent to the size of Montana.

Only 11 percent of this terrain can grow crops because mountains and forests cover the majority of the country. Defying the limitations of its geography, Japan's estimated population in 2014 borders on 127 million people. Thus, the issue of space figures prominently in Japanese culture.

Japan's society can appear culturally and ethnically homogeneous. Though a number of significant minority groups do exist in Japan, the Yamato ethnic group makes up ninety-eight percent of the population, and the vast majority of citizens speak Japanese as their primary language.

Despite its reverence for traditional beliefs and aesthetics, Japan is known for innovation. The country incorporates aspects of Western culture without compromising its own strong cultural identity. Beyond balancing new with old, the Japanese incorporate each to inform technological advancements that continue to amaze the rest of the world.

History

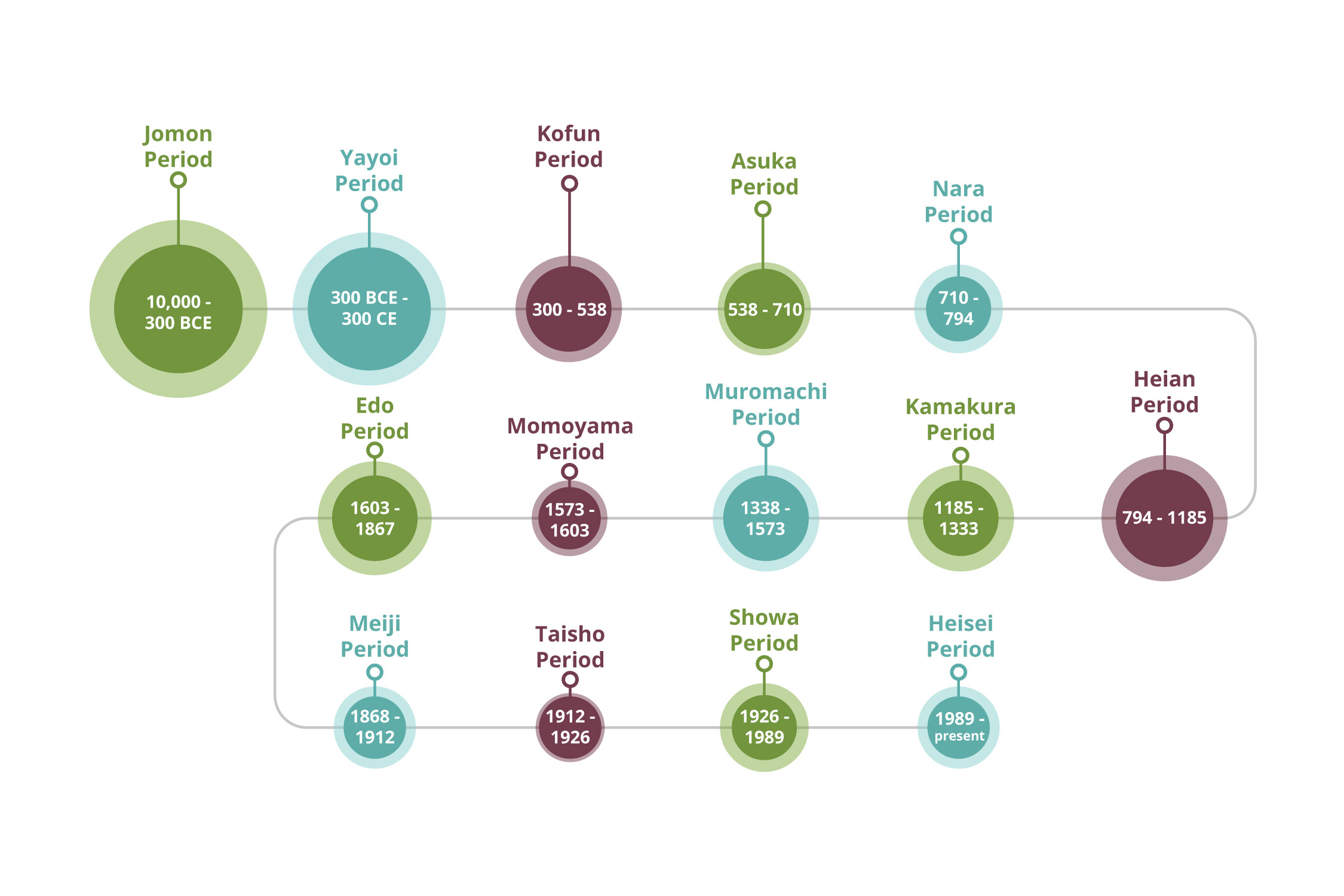

Japan's history is separated into fourteen periods: the Jomon (10,000-300 BCE), Yayoi (300 BCE-300CE), Kofun (300-538), Asuka (538-710), Nara (710-794), Heian (794-1185), Kamakura (1185-1333), Muromachi (1338-1573), Momoyama (1573-1603), Edo (1603-1867), Meiji (1868-1912), Taisho (1912-1926), Showa (1926-1989), and Heisei (1989-present). More broadly, Japan's history is divided into intense periods of alternating isolation and foreign influence. For example, during the 5th and 6th centuries, Japan imported China's systems of religion (Buddhism) and government, along with their music and other arts. Buddhism's subsequent growth during the Nara period (710-794) motivated the construction of many temples.

The 16th century, however, was characterized by less permeable borders; Japan responded to European traders and missionaries by implementing strict regulations against foreign influence. The most notable of these edicts was a ban against Christianity issued in 1588. For hundreds of years afterwards, Japan successfully isolated itself from Western art and culture. Much of the country's traditional music, or hōgaku, was developed during this relatively peaceful, prosperous period.

Isolation, however, became difficult to sustain. Japan successfully held off the push of colonialism until July 8th, 1853. On that day, Commodore Matthew Perry of the United States opened Japan's doors to the Western world for the first time in centuries by forcing Japan to enter into trade with America. To avoid becoming another colonized area of the West, Japan's powerful feudal lords consolidated forces. They instated Emperor Meiji, who had previously occupied a relatively powerless position, as the central figure of their government. Edo was renamed Tokyo, and became the official capital of Japan. The era that followed, referred to as the Meiji Restoration, became a catalyst for industrialization in Japan.

Warding off Western occupation required more than internal government reorganization. Japan strategically adopted Western technology, mannerisms, and pedagogy to obviate colonization. Echoing the Nara period's openness to Chinese and Korean ideas, the Meiji period induced a more porous Japanese culture. Many important changes occurred, led by the economy's conversion from agriculture to industry. Japan also established a nationwide educational system that incorporated Western music.