The First Great Awakening

It is eminently clear that enslaved Africans had been making music well over a century before The Great Awakening in America, 1720-1740. There was clearly no decline in the Transatlantic Slave Trade; however, with community at the heart of African culture, it was the duty of the slaves to teach those who came after them. To this extent, one would assume the emotional fervor in the songs of the slaves would have, in some way, influenced the White congregations and their religious experiences.

The Protestant Evangelical movement found its roots in the Age of Enlightenment that swept through Europe during the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Often referred to as The Age of Reason, the movement fostered philosophical ideas relative to humanism, religion, the division of Church and State, and liberty in governed affairs.

A group of Protestant English ministers fueled The Great Awakening by traveling the American colonies preaching and teaching with an evangelical zeal. Their message called for redemption and a personal relationship with God through Jesus Christ.

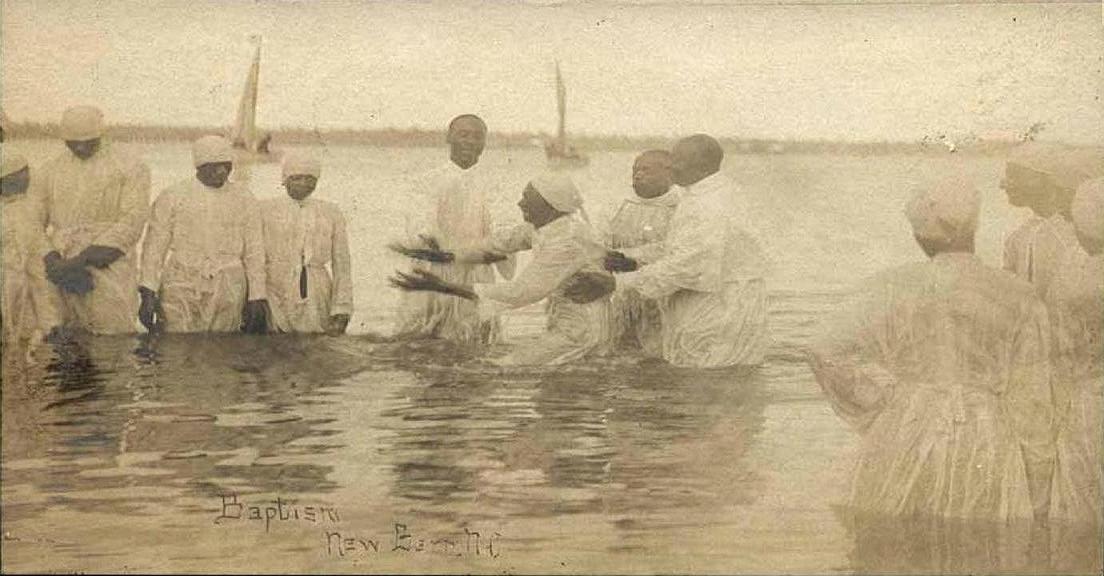

In his book The Black Church, Henry Louis Gates Jr. records that these revivalistic gatherings, for both Black and White attendees, were full of dramatic preaching, shouting, dancing, fainting, ecstatic trances, and baptism rituals that evoked the religious celebrations of the African ancestors of the enslaved (Gates 2021, 40). It should come as no surprise that this was the first time when the slaves embraced Christianity in mass numbers. The revival movement also brought with it a new style of singing. Europe has waxed cold of the psalmody imposed by the Catholic church. With a new preference for religious poetry among the American colonists, Isaac Watts's, John Wesley's, and George Whitefield's hymns became common among the colonists and quite valuable for the slaves.

The text in these hymns, including the one referenced in the graphic, "When I Can Read My Title Clear," seemed to have resonated deeply with the experiences of slave culture, however, not in the songs' original form but rather in an acculturated way where the words applied to their lives and condition. Later referred to as the Old 100's, these hymns took on the form of long metersA quatrain (four-line stanza) in iambic tetrameter, which rhymes in the second and fourth lines and often in the first and third. The syllable count of each line is 8.8.8.8. or lined hymnsPerformance involves the chanting (or "lining out") of one or two lines of the hymn by a leader, to which the congregation immediately responds by singing, without accompaniment, the hymn lines to the appropriate tune. in the Black religious experience.

The practice of lined hymns comes from the feature of call-and-response. However, in this practice, illiterate slaves used the call as a tool to repeat the same line as if they were learning the songs by rote. Listen to an example of lined hymnWhen I Can Read My Title Clear:"

When I Can Read My Title Clear [ 00:10-00:36 ]

American Folk Music (Southern)

The above video is a stark difference from the original: When I Can Read My Title Clear - Isaac Watts .

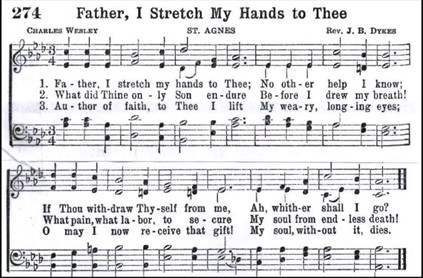

Slaves also employed the technique of a long-metered hymn, as it allowed them to emote the text in a relatively different way simply because they had experienced it. The long-metered hymn is when the phrasing of a passage of text is elongated twice its value. Instead of four bars to a phrase, it extends eight bars per phrase. Listen to the following example "Father I Stretch My Hand to Thee" .

Father I Stretch Out My Hands to Thee

Dr. H. Beecher Hicks, Jr.

The oppressors required something that was of great value from the oppressed, only to make a mockery of their religion.

Steal Away to Jesus

My Lord, He calls me. He calls me by the thunder.

The Trumpet sounds within my soul. I ain't got long to stay here.