The Ring Shout in America

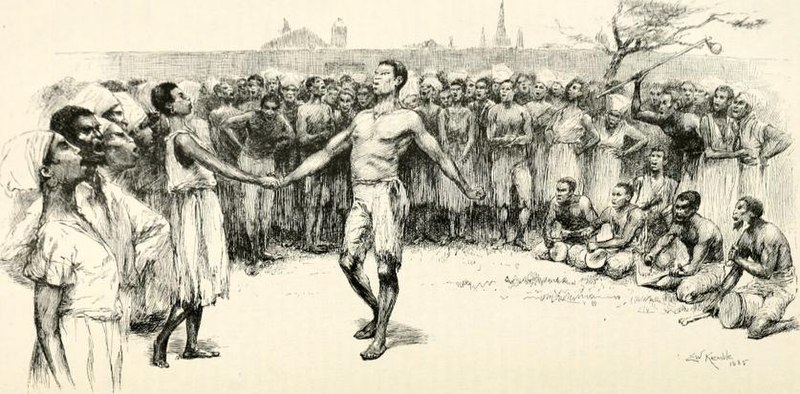

The inseparable entities of rhythm, dance, and song were the primary means by which enslaved Africans retained their cultural identity in America. Though enslaved Africans often could not speak with each other, music and the responses thereof were a common language between the estranged Africans. Of particular note, the African ring shout ritual was of paramount import.

Both Samuel Floyd and Sterling Stuckey, two of the foremost scholars in African American studies, credit the African ritual of the ring shout as the impetus of African American expression in the new world. Dance, drum, and song were the critical components of this ritual in so much as it "validated and heightened conflicting and contrasting expressions and interpretations and established, built, and sustained accord" (Floyd 1995, 20).

When one thinks of a ring, there is no beginning or end. The circle is complete in itself. Such is the significance or symbolism of the ring shout ritual as practiced throughout Central and West Africa. Unity and solidarity among villagers gathered in the circle are essential. Traditionally, Africans would move single file in a counterclockwise direction with the drums in the circle's center. By doing so, they believed they evoked their ancestors' spirits of protection and wisdom. While striving to live in the present, supplications, reverence, spiritual renewal, and hope were made manifest to the Creator of the Universe. The purpose of the ring shout was to make it evident that God is the past, present, and future. With the understanding of music, rhythm, and body moment as essential components of African and African American spirituality and religion, Marcus James makes a salient statement in his article "Christianity in the Emergent Africa": "The African is incurably religious. To him, the spiritual world is real and near. His art, his music, his dance, all are variations of the theme of his religion, and nowhere does religion permeate social life more thoroughly than in an African community" (James 1956, 238).

Once evangelical Christianity took hold among the enslaved Africans, they began meeting in praise houses covertly to practice Christianity in a way that was meaningful to them without being observed by slave owners. Ring shouts played an integral role in this early practice, both connecting enslaved Africans to their common past and in their present circumstances. Because of bonds created in the brush arbors and praise houses and through the ring shouts, the new African Americans were able to survive the loss of their shared languages and customs.

In the words of Albert Raboteau, "even as the gods of Africa gave way to the God of Christianity, the African heritage of singing, dancing, spirit possession, and magic continued to influence African American spirituals, ring shouts, and folk beliefs. That was evidence of the slaves' ability not only to adapt to new contexts but to do so creatively (Raboteau 1978, 92)."

Beyond the Africanisms in the dialect and certain melodies, the most demonstrably African survivor from the slaves' earliest days in North America is the ring shout or shout. Even the word shout is possibly of African origin-linguist Lorenzo Dow Turner links it to the West African Islamic word saut, meaning to move or dance around the Kaaba, the building in Mecca holding Islam's holiest artifacts. Depending on the part of the South where it was heard, the term shout refers to either the music or the dance or the combination of the two. And whereas few of the chroniclers of the early spirituals were trained musicologists, even the most rudimentary journalist could describe this direct link to African origins.

Rev. Johnson

It was something in the religion of the oppressors the slaves saw which was deeper than that of the oppressors' presentation.

Albert Raboteau

...even as the gods of Africa gave way to the God of Christianity, the African heritage of singing, dancing, spirit possession, and magic continued to influence African American spirituals, ring shouts, and folk beliefs.