African American Field Hollers and Work Songs

Slaves incorporated rhythm, body movement, and songs into their daily tasks. They created the work song, perhaps the most indigenous music genre of the African Diaspora. Heavy accents on alternating beats helped to synchronize the labor at hand. Ethnomusicologist Olly Wilson asserts: "The process of chopping wood becomes an intrinsic part of the music, wherein the work becomes the music, and the music becomes the work" (Wilson 1983, 50).

These songs often contained codified messages, stories from the Bible, and encouraging words. From the fervent cries in the fields, to improvised rhythmic chants of workers on the docks, to voices heard from victims of peonage, America is built on labor, and its history is hidden in a song.

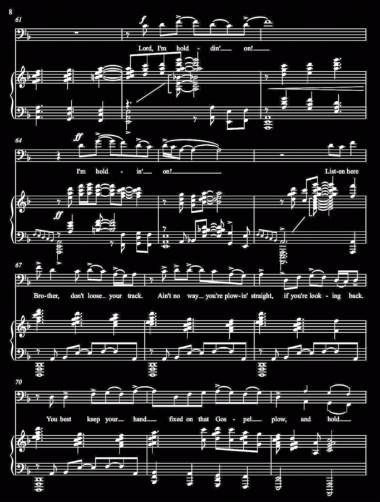

The image here is an excerpt from "Hold On" by Steven M. Allen, an extension of the traditional work song that juxtaposes rhythms of the Afro-Cuban Son and the ring shout. The two do not necessarily produce polyrhythm but, rather, present cross rhythmic patterns that accentuate one another.

In the video "Hold On" find the Son Rhythm at this mark 00:14-00:42. Notice that a series of eighth notes with accents on two and four comprise the Son rhythm. The work song, however, accentuates the opposite beats (one and three). The example shows how the voice takes beats one and three, while the Son occupies beat two and uses beat four from the ring shout. The cross rhythmic effects occur on the upbeats of beat two from the ring shout and three from the Son.

Hold On

As many work songs employ Biblical parody, the text here is taken from Jesus' admonishment to his disciples when they were filled with reasons for wanting to return home before following Him: "No one, having put his hand to the plow, and looking back, is fit for the kingdom of God" [Luke 9:62, NKJV]. Instead of dialect, the vernacular use of language: "ain't no way you plowing straight, if you're looking back" is presented as a point of the ongoing relevancy in socio-cultural issues. This is referring to the verse from "Hold On" that states: "Nora said, Ya lost yo' track, Can' (can't) plow straight an' (if you) keep a-lookin' back."

Luke 9:62, NKJV

No one, having put his hand to the plow, and looking back, is fit for the kingdom of God

Ashenafi Kebede

There is no doubt that these calls were African in derivation and that they were sung in African dialects in the early part of slave history.