Composition: Textual Rhyme Scheme

There are several definitions of the religious-based African American folk musicA term used to describe music of the common people that has been passed on by memorization or repetition rather than by writing, and has deep roots in its own culture. Folk music has an ever-changing and varying nature and is deeply significant to the members of the culture to which it belongs. that first came to the general public's attention in the late 1860s. One scholar described spirituals as "Musical poems, not attributable to any specific poet or composer, of the early Afro-American's view of life which, through the evolution of their fame and usage, acquired set arrangements of melody, form, harmonic treatment, and text" (Tyler 1980, 15).

From a textual standpoint, John Lovell, Jr., characterizes them as possessing "a careful organization of a vivid first line, a middle refrain line, and a chorus. The repetitions are mainly singing devices, memory aids, and means of enlisting and holding the group's support. These methods appear in many folk songs, but in the spiritual they are generally meshed with originality and taste" (Lovell 1972, 215). Southern adds the distinguishing characteristic that most spirituals feature four-line stanzas in the aaab rhyme scheme (three repeated lines and a refrainA verse which repeats throughout a song or poem at given intervals.) or the aaba format (two repeated lines, one new line, then a repeat of the first). On some occasions, but less frequently, the rhyme scheme used is the abcd form (with no repetition of text) (Southern 1997, 188-190):

Lyrics

We'll run and never tire, (a)

We'll run and never tire, (a)

We'll run and never tire, (a)

Jesus sets poor sinners free. (R)

Way down in the valley, (a)

Who will rise and go with me? (b)

You've heard talk of Jesus, (c)

Who set poor sinners free? (R)

We'll run and never tire, (a)

We'll run and never tire, (a)

We'll run and never tire, (a)

Jesus sets poor sinners free. (R)

The structure of the rhymed patterns with repetition of text encourages frequent use of the now-familiar African call-and-responsePerformance style with a singing leader who is imitated by a chorus of followers. This is also known as responsorial singing. (or, as some observers call it, "call-and-recall" [Spencer 1987, 6]) format, with alternating solo verses with refrains (Southern 1997, 188).

However, neither the aaab nor the aaba rhyming sequences are universally applicable, as Southern is quick to add. For instance, not all spirituals feature rhyme schemes. Since most spirituals grew out of spontaneous pastor/congregation interactions, people didn't value rhymed couplets as highly as an honest expression of faith. "Since the lead singers extemporized the words of a song as they went along," she writes, "they had no time to think about rhyme, so great was their concern for the ideas they wanted to express. Perhaps during the choral response, they could think ahead a bit, but not always to the extent of perfecting the rhyme. The next time the song was sung, the leader might improvise different words in response to a different set of circumstances, or a different person might lead the singing" (Southern 1997, 199).

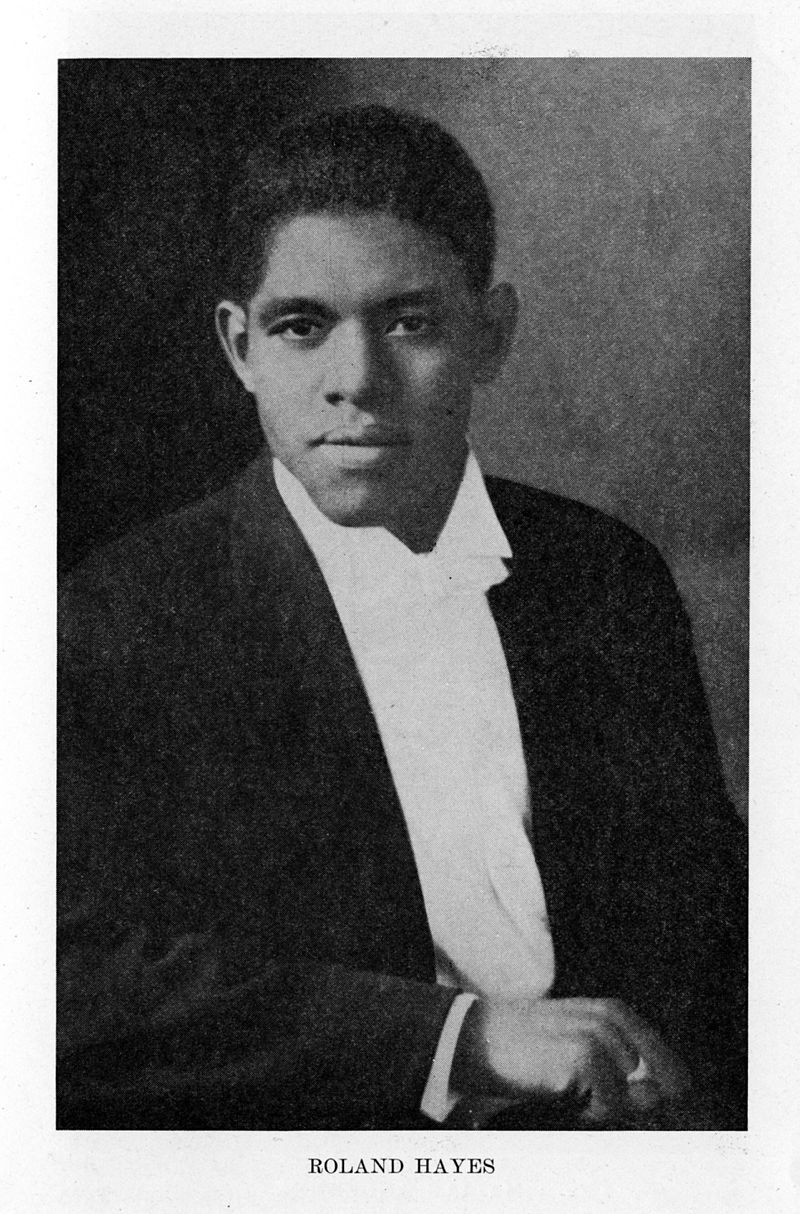

Listen to the following arrangement by Roland Hayes and determine the textual and melodic rhyme scheme-this listening exercise can be completed in class.

| "Lit'l Boy"

by Roland Hayes |