Music of the Spirituals 2

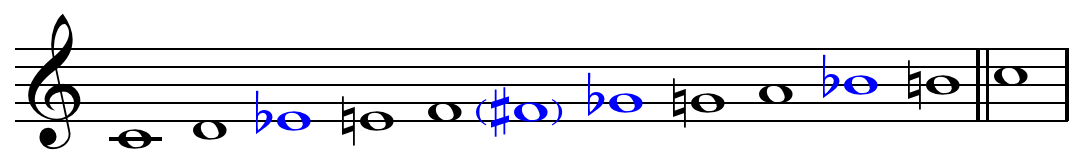

Although John W. Work claimed it was ''impossible'' to accurately record the ''extravagant postamentaA technique of gliding from one note to another without actually defining the intermediate notes; a smooth sliding between two pitches. This term is used primarily in singing and string instruments. Often called glissando for other instruments, especially the trombone. [portamento], slurs, and free use of extra notes'' found in spirituals, he was very interested in studying the scales commonly used by slaves in their composition:

[The slave composer] unconsciously avoided the fourth and seventh major scale steps in many songs, thereby using the pentatonic scale. But there were employed notes foreign to the conventional major and minor scales with such frequency as to justify their being regarded as distinct. The most common of these are the 'flatted third' (the feature note of the blues) and the 'flatted seventh.'

(Work 1940, 26)

The musical device of bending the note, which later became known as the famed " blue noteA slight drop of pitch on the third, seventh, and sometimes the fifth tone of the scale, common in blues and jazz. Also known as bent pitch.," represents the resolution to this apparent dichotomy in the major or minor key perception of spirituals-certain tones in the major and pentatonic scale are "flattened" or "bent" to a lower pitch (Southern 1997, 191). Using the transcriptions of the spirituals in Slave Songs of the United States, Southern says that the seventh tone of the scale is ''flatted, indicating that the tone was sung lower than normally'' (Southern 1997, 191). The legendary blues artist W. C. Handy (1873-1958) described the "curious, groping tonality" of the "blue note" as a "scooping, swooping, slurring tone." He identified it as one of the markers indicating the African origins of the practice, whether African Americans used it in spirituals or the blues (Southern 1983, 214).

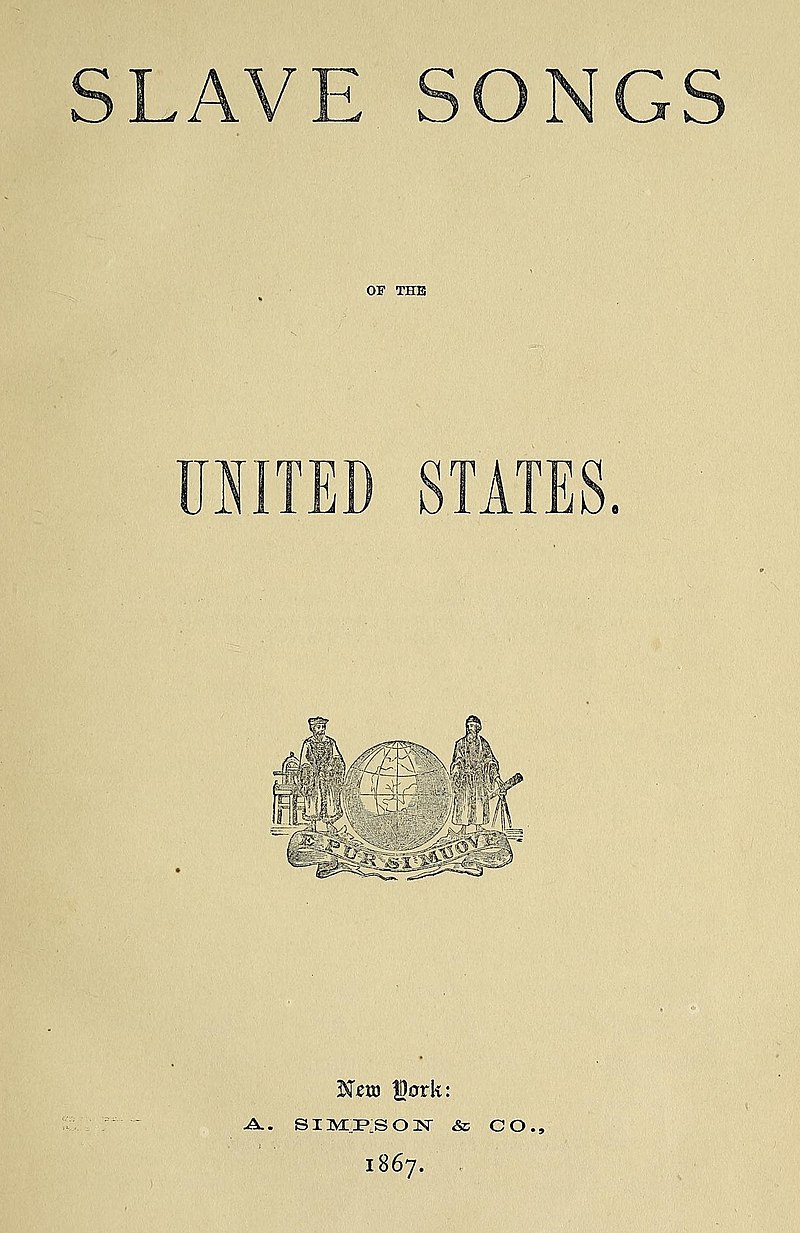

Still, the writers who first chronicled spirituals in the 1860s often commented that many of the songs were sad and in a minor key, and consequently, the misconception that all spirituals were in a minor key has lingered to the present day. But other than Lucy McKim Garrison (1842-1877), few early collectors were trained musicians. Henry Krehbiel's (1854-1923) study shows that spirituals in minor keys did not predominate-they only sounded so because of their sad nature and ''alien'' progressions and changes (to Western-trained ears, anyway). Krehbiel drew from the top collections of spirituals of the day and examined 527 spirituals. These collections included:

- Slave Songs of the United States

- The Story of the Jubilee Singers

- Religious Folk Songs of the Negroes as Sung on the Plantations (originally Cabin and Plantation Songs)

- Bahama Songs and Stories

- Calhoun Plantation Songs

His trained analysis of the "intervallicThe distance between two pitches. structure of their melodies" produced the following table (8.1) and effectively ended the notion that the majority of spirituals are in a minor key:

| Ordinary major | 331 |

| Ordinary minor | 62 |

| Mixed and vague | 23 |

| Pentatonic | 111 |

| Major with flatted seventh | 20 |

| Major without fourth | 78 |

| Minor with raised sixth | 8 |

| Minor without sixth | 34 |

| Minor with raised seventh (leading tone) | 19 |