Conclusion

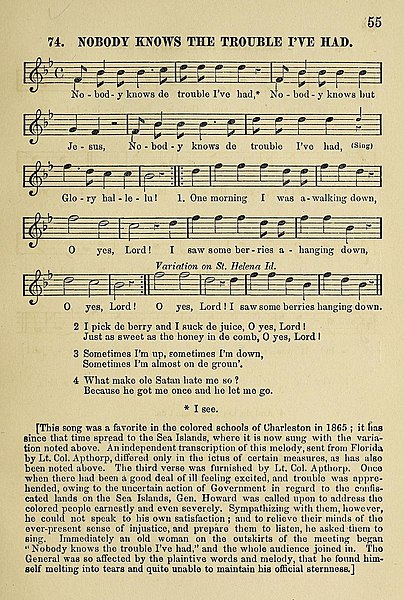

As noted earlier, much discussion by scholars exits surrounding the origin and use of the term "spiritual" to describe the antebellum folk songs and their continuous development during the post-Reconstruction era and beyond. These early folk songs-sung without accompaniment-developed extemporaneously en masse out the crucible of enslaved Africans living under degrading conditions. Slave Songs of the United States uses the term "sperichils" to describe their music. Other scholars, including Lydia Parrish, prefer to use terms such as slave songs, slave hymns, plantation songs, ballads (or ''ballats"), and, especially, anthems. Regardless of where one stands in this debate, the oldest of literature, the Bible, refers to three types of songs: psalms, hymns, and spirituals-Colossians 3:16. Some of the song texts were so precious and endearing to the enslaved Africans that these useful phrases are known to scholars in the field as "wondering refrain," meaning they make their way into various spiritual.

Although the three Northerners Allen, Ware, and Garrison left an important early folk song documentary legacy in Slave Songs of the United States, the original Fisk Jubilee Singers of Fisk University also left a lasting legacy by introducing and preserving these same folk songs and their additional arrangements to the world between 1871 and 1878. Fisk University, which today continues this legacy through its choral group of the same name, had its humble beginning in 1866 because of the American Missionary Association that was instrumental in establishing this institution and many others that are now considered Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU). With the importance of spirituals' impact on the world by the Fisk Jubilees Singers, classically trained composers such as Harry T. Burleigh, Roland Hayes, and others began to arrange the spirituals for voice and piano. Today, these arrangements are an essential part of recitals in music schools and conservatories.