African American Music in the Civil Rights Movement 1

Was the civil rights movement necessary? After reading the aforementioned information on the key events of the civil rights movement and viewing the film Soundtrack for a Revolution, one may also ask, "Why did mainstream America before and during the signing of the Civil Rights Act put so much effort in preventing Black people from experiencing equalities, social justice, fair housing, and work with fair wages?" The need to maintain power, prestige, and resources are often the reasons that lie behind such actions. A significant number of mainstream Americans were not willing to share their entitlement with those who they felt were inferior to them.

Writings from a European perspective heavily influenced perceptions of African American people despite the pioneering research on African American culture and history by African American politicians, writers, and educators from small, historically Black institutions conducted as early as the 1870s, in which the issues of race, culture and class surfaced as central themes (see Trotter 1878; G.W. Williams 1882-83). Consequently, many "negative images and representations of African Americans were institutionalized within academic and popular cultures" (Banks 1996, 364), images and representations whose source lay in the descriptions of the songs, dances, and lifestyles of African slaves that had appeared in the diaries, journals, reports, and memoirs of slave traders, slaveholders, travelers, and missionaries in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and had become reference points for the negative portrayal of African slaves in North America. Interpreting the cultural expressions of the slaves through the lens of European values and conventions, these observers characterized the slaves' music, dance, and playing of instruments as "barbaric," "wild" and "nonsensical" (B. Jackson 1967; Epstein 1977; Southern 1983; Southern and Wright 1990).

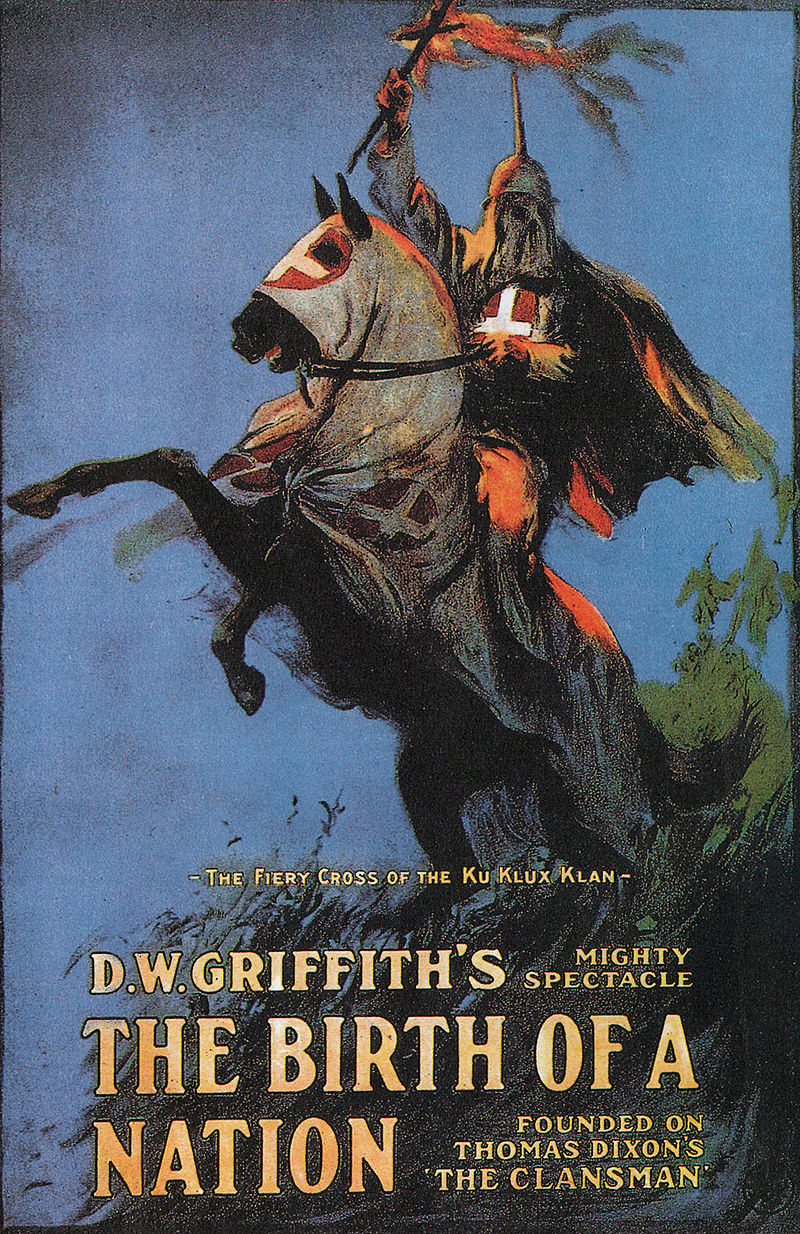

By the nineteenth century, such representations had become institutionalized in North American popular culture through blackface minstrelsy, a theatrical form that featured White performers in blackened faces as caricatures of African Americans, and films that followed such as in the video "Birth of a Nation (1915)". In turn, these detrimental visual images, combined with the negative representations of Blacks in early literature, influenced the assessment and tone of writing about African American music in the twentieth century.

The Birth of a Nation 1915

The bleak outlook for African Americans living in a society that regarded them as inferior was, however, once more offset by positive representations within African American culture. For instance, the Harlem Renaissance [see Unit IV, lesson 12] (1921-1933), was the most significant display up to that time of African American pride and excellence as expressed through literature, music, art, and dance, which effectively opposed social and civil injustices prior to the civil rights movement.

We Shall Not Be Moved

Oh I, shall not

I shall not be moved I shall not

I shall not be moved

Just like a tree planted by the water

I shall not be moved

Martin Luther King, Jr.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.