Conclusion

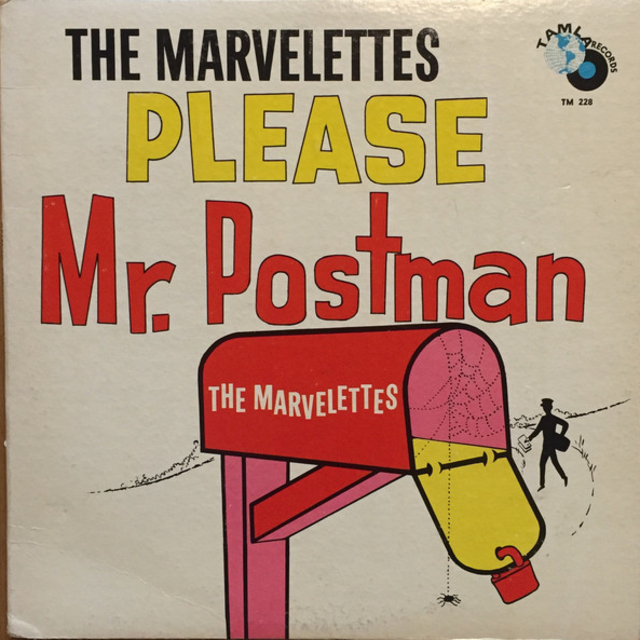

In the early days of soul music, soul musicians and record companies were subject to much of the same discrimination and racism that all Black people in America experienced. During the earliest days of soul music, the 45-rpm single was the dominant medium of commerce, with relatively few soul artists having their music released in the album format. A number of the earliest soul albums featured cartoon drawings on the cover rather than photographs of the actual artists so that the albums had a greater chance of being stocked by Southern record stores in White neighborhoods. Examples include the Marvelettes' Please Mr. Postman and Rufus Thomas's Walking the Dog albums. However, this was a relatively short-lived practice, although as late as 1965, Otis Redding's Otis Blue album featured a photo of a thin, graceful White female model rather than a shot of the artist himself.

After the phenomenal 1969 success of Isaac Hayes's Hot Buttered Soul (1969) album transformed the political economy of the Black music industry, companies spent much more time and money on the artwork for soul LPs. The apotheosis of this was the elaborate cover for Hayes's Black Moses (1971) album, which folded out into a cross shape with Hayes dressed up in a colorful African robe, his hands and arms stretched out to the sides in a striking, Christ-like pose. Perhaps the Civil Rights Act signed in 1964 was more far-reaching than imagined. Blacks were feeling more empowered with the possibility America would become the place of true freedom, equality, and social justice for all, not just Whites. If it were to sustain its place and significance to society, the music industry needed to reflect these changing times.

Long Walk to D.C.

It's a long walk to DC but I've got my walking shoes on

I can't take a plane, passer train, because my money ain't that long

America we believe, oh that you love us still

So people I'm gonna be under to wipe away my tears