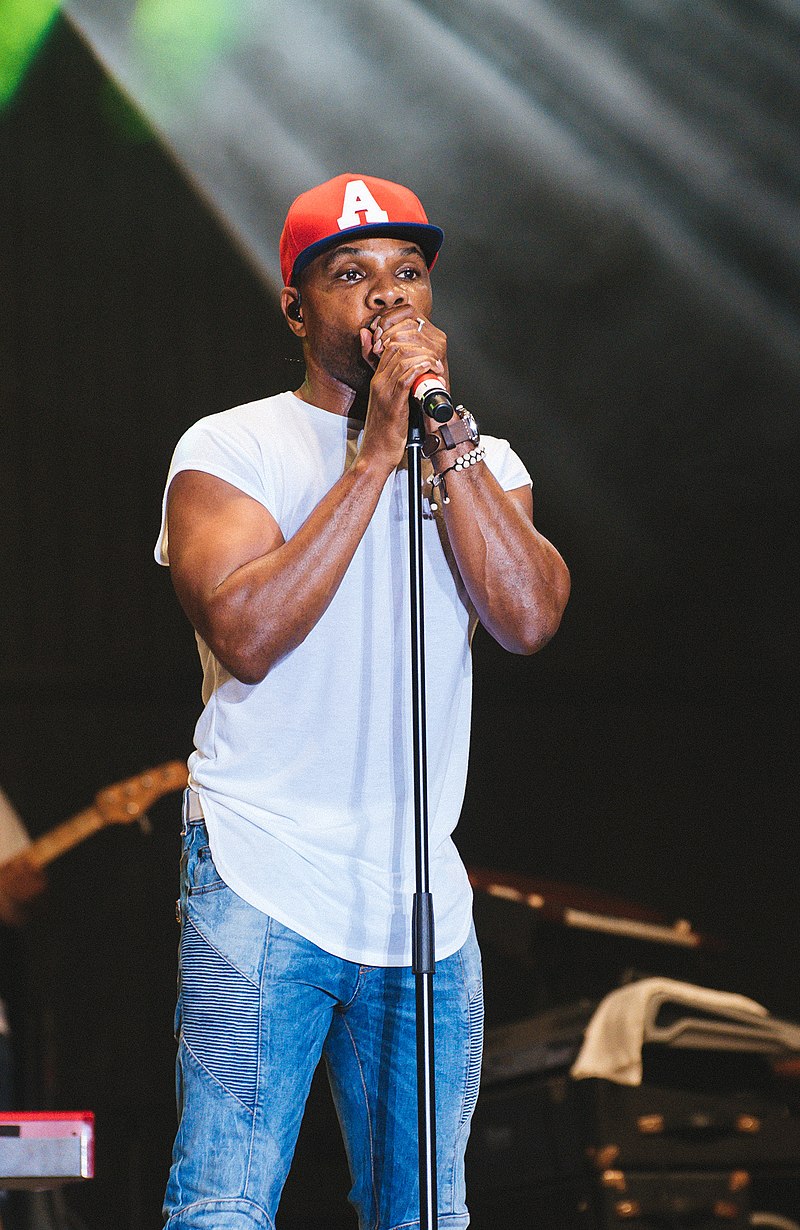

Kirk Franklin and "Stomp"

The last watershed moment in the growth and expansion of the new contemporary gospel sound came in 1997 in the form of a musical declaration in a song made by Kirk Franklin through the release of " Stomp The opening lyrics of this urban contemporary gospel sound declared in its opening lines:

Lyrics

For those of you that think gospel music has gone too far

You think we got too radical for Christ

Well I got news for you, you ain't heard nothin' yet

And if you don't know now you know. Glory, Glory!

Kirk Franklin, "Stomp"

These words constitute a type of manifesto with R & B and hip-hop overtones punctuated by Salt of Salt-N-Pepa.

Kirk Franklin - Stomp (Dance Video) | quintonakeem. [ 00:00-00:00 ]

As often happens, the objections of some cranks got reworked into a selling point, and the song ['Stomp'] sold. Upon its May 27 release, the album God's Property from Franklin's Nu Nation debuted at no. 3 on the Billboard 200 and became the first gospel album to top the magazine's R & B/Hip-Hop Albums chart. In July, 'Stomp' briefly became the most played song on R & B radio, bumping elbows with Biggie, both himself ('Mo Money Mo Problems') and his ghost (Puff Daddy's 'I'll Be Missing You').

(Langhoff 2019, n.p.)

Similar to the criticisms hurled at Dorsey and Hawkins concerning their brand of gospel music, Kirk Franklin "also faced criticism from traditional church people who felt his urban style and energetic dancing were inappropriate with Christian music" (Lawton 2016, n.p.). "The backlash from gospel communities wasn't hard to understand. People are often inclined to draw well-defined lines around their experiences to help them navigate the world; things become either good or bad, holy, or evil, Gospel or secular, black or white" (Younger 2017, n.p). But Franklin would retort back, stating:

I don't believe in a particular musical sound, but I do believe in a particular message. Regardless of the beat or the groove, the music has to draw us to the cross. That's the real reason for the existence of gospel music in the first place. If it doesn't do that, then I'd say it's a failure, regardless of the sound.

(Franklin 1998, 19)

Music critics state that "during [Franklin's] more than twenty-year-long career, [he] has revolutionized gospel music, blending it with R & B, rap, pop, and hip-hop. He has received ten Grammy awards and has sold more than ten million albums" (Lawton 2016; Kimo 2018).

These three watershed moments in the development and globalization of gospel music, approximately thirty years apart, reveal the acceptance of the core values of gospel music in blended and/or hybrid forms by generations of composers, performers, and listener-consumers. The gospel musicians of Dorsey's, Hawkins's, and Franklin's generations had to confront the sacred and secular dichotomy within the church and the world-as did musicians who came before and after. Still, the music has continued and will continue to evolve.