Origins

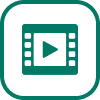

Although it is impossible to determine the precise date of the origin of the spiritual, it's development can be classified into three primary periods: (1) before 1830, (2) 1830 - 1850, and (3) 1870 - present, as shown in table 5.1.

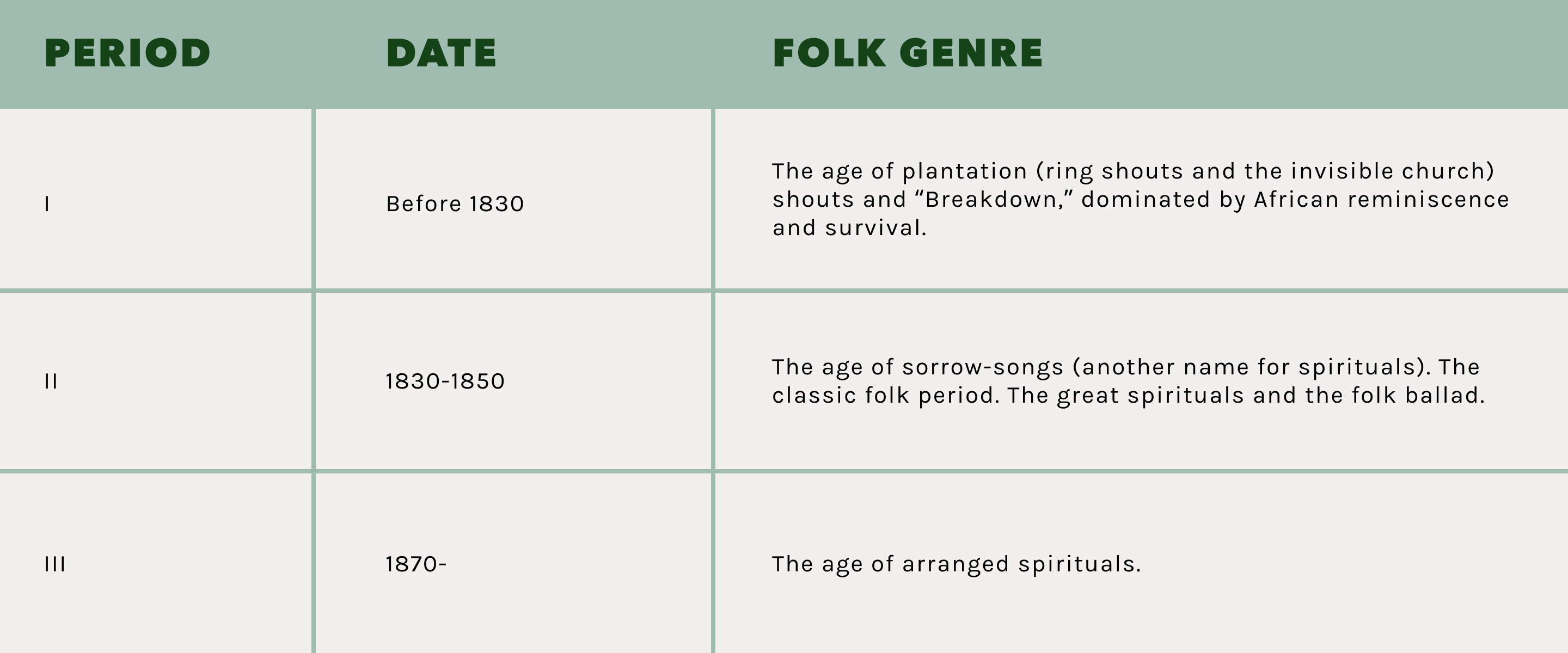

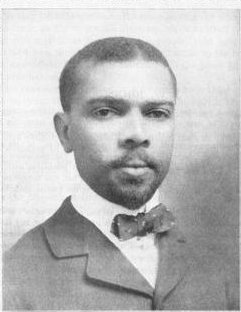

Testimonies of ex-slaves document folk spiritualsThe earliest form of indigenous a cappella religious music created by African Americans during slavery. as the progeny of the Black collective rather than the individual composer. Poet James Weldon Johnson attributes their origin to "Black and Unknown Bards," the title of a poem he wrote in 1917. As music was created and transmitted via the oral traditionOral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas, and cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another. The transmission is through speech or song and may include folktales, ballads, chants, prose, or verses., the date of the origin of the spiritual can only be surmised from the earliest extant accounts of observers who documented their experiences of religious music performed by Black people.

Although the first Africans arrived in the British North American colonies in 1619, the Christianizing mission did not begin in earnest until over 100 years later. It should be noted as a reminder-as noted in Lesson 2-that for the enslaved Africans this was not their first encounter with Christianity ![]() SIDE NOTEThere are also communities of Ethiopian Christians. These are by no means recent converts to Christianity, for Christianity was accepted as a state religion c. 333 A.D., just a few years after the Edict of Toleration made Christianity the state religion in Rome (p. 20). ("The Black Perspective in Music": The First Ten Years Author(s): Ron Byrnside Source: Black Music Research Journal, 1986, Vol. 6 (1986), pp. 11-21 Published by: Center for Black Music Research - Columbia College Chicago and University of Illinois Press,. Concerning the enslaved African's embracement of this new Christian mission, it should not be a surprise Henry Louis Gates, Jr. states "that enslaved Africans in North America did not accept Christianity-when finally offered a chance to embrace it-exactly as white Americans practiced it or pictured it. Instead they reshaped it in their own images, to satisfy their own spiritual and practical needs…" Gates further states in quoting Reverend Yolanda Pierce, dean of the Howard University School of Divinity, that the "African American adopted Christianity, but I also think they adapted Christianity" (Gates 2021, 16).

SIDE NOTEThere are also communities of Ethiopian Christians. These are by no means recent converts to Christianity, for Christianity was accepted as a state religion c. 333 A.D., just a few years after the Edict of Toleration made Christianity the state religion in Rome (p. 20). ("The Black Perspective in Music": The First Ten Years Author(s): Ron Byrnside Source: Black Music Research Journal, 1986, Vol. 6 (1986), pp. 11-21 Published by: Center for Black Music Research - Columbia College Chicago and University of Illinois Press,. Concerning the enslaved African's embracement of this new Christian mission, it should not be a surprise Henry Louis Gates, Jr. states "that enslaved Africans in North America did not accept Christianity-when finally offered a chance to embrace it-exactly as white Americans practiced it or pictured it. Instead they reshaped it in their own images, to satisfy their own spiritual and practical needs…" Gates further states in quoting Reverend Yolanda Pierce, dean of the Howard University School of Divinity, that the "African American adopted Christianity, but I also think they adapted Christianity" (Gates 2021, 16).

James Wheldon Johnson

It was not until the religious revival known as the Great AwakeningPeriod of religious revival that swept the American colonies in the mid-eighteenth century., which began around 1740 (Raboteau 1978, 128), that significant numbers of slaves converted to Christianity, a prerequisite for the birthing of the Negro spiritual. The dissenting Protestants involved (Congregationalists, Presbyterians, and a yet informally organized group known as Methodists), founded their revival on the egalitarian belief that divine grace was available for all and placed great emphasis on the importance and validity of personal religious experience. Responding to a conversion strategy based on these principles, rather than on instruction through catechism, as had been the case earlier, Black people began to answer the call to Christianity in numbers sizable enough to generate notice.

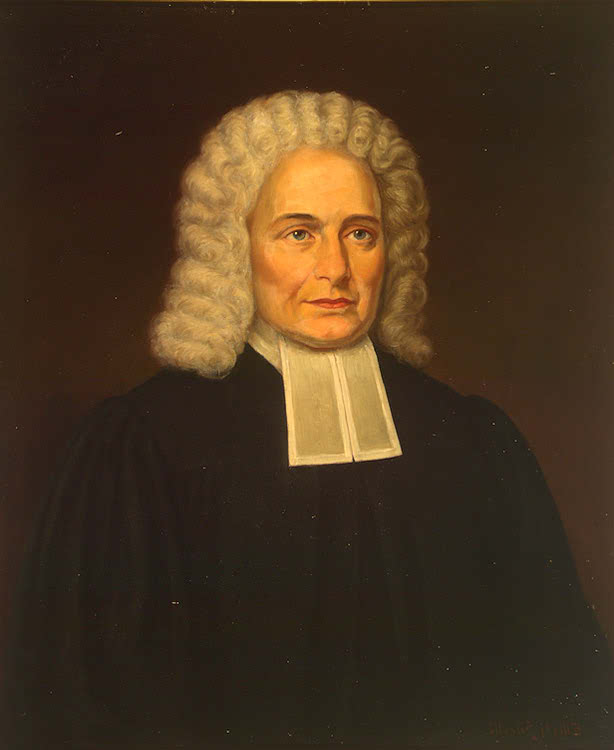

Writing of his experience in Virginia in the mid-1700s, Presbyterian clergyman Samuel Davies ![]() SIDE NOTE

SIDE NOTE

"Black Singers and Instrumentalists of Early America" as quoted in Eileen Southern's Readings in Black American Music. (pp. 28.) "…According to Eileen Southern, "The Presbyterian minister Samuel Davies (1723-61) did missionary work in Virginia before he became president in 1759 of Nassan Hall (later Princeton University) in New Jersey. Some of the letters sent by Davies and other clergymen to sympathetic 'benefactors' in London requesting psalm books and Bibles for members of their parishes, both Black and White, were published in book form. From a letter written by Samuel Davies in 1755 to 'a friend and member of the Society in London for promoting Christianity,' he states, 'The books were all very acceptable, but none more so than the Psalms and Hymns, which enable them [i.e., the slaves] to gratify their peculiar taste for psalmody. Sundry of them have lodged all night in my kitchen, and sometimes when I have awaked about two or three o'clock in the morning, a torrent of sacred harmony has poured into my chamber and carried my mid away to heaven. In this seraphic exercise, some of them spend almost the whole night. I wish, Sir, you and other benefactors could hear some of these sacred concerts. I am persuaded it would surprise and please you more than an Oratoria or a St. Cecilia's day….'" (Southern 1983b, 28). described seeing 100 or more Black people at services he led, while Methodist Bishop Francis Asbury noted in his 1793 journal a South Carolina congregation of over 500, with "three hundred being black" (quoted in Epstein 1977, 106).

We have too a growing evil, in the practice of singing in our places of worship, merry airs, adapted from old songs, to hymns of our composing, often miserable as poetry and senseless as matter, and most frequently composed and sung by the illiterate blacks of the society … the evil is only occasion- ally condemned, and the example has already visibly affected the religious manners of some whites.

(Southern 1983b, 62-3)

Although the music to which Watson refers is not classified as spirituals, his comments clearly establish the existence of a well-defined body of song-repertoire by Blacks in 1819. The distinguished musicologist, Eileen Southern, refers to this body of song-repertoire as "one of the most vivid descriptions of early Negro spirituals and the shout" (Southern 1983b, 62). Watson makes it clear that this distasteful music performed by Black Methodists, in reference to the followers of Richard Allen, was distinct from that of standard White practice, and that it was sufficiently pervasive and compelling to influence musical practice across the Black-White divide.

In her seminal work Sinful Tunes and Spirituals (Epstein 1977), Dena Epstein suggests that this maligned repertoire could well have "referred to what became known as Negro spirituals," although that label does not appear specifically in print prior to the Civil War (Epstein 1977, 219). Epstein argues that it is likely that the characteristics that defined this musical expression as unique existed prior to Watson's critique (Epstein 1977, 232). Certainly, there were significant numbers of Black Christians in the southern colonies by the end of the eighteenth century, and independent African American church bodies had also been established by that point (Raboteau 1978, 131). Furthermore, the spirit of resistance to physical and cultural subjugation had been operative among the slave population from its earliest existence in the colonies. Viewed collectively, these contentions suggest a late eighteenth-century origin for the spiritual.

Walk Together Children

O, walk together children

Don't you get weary

Walk together children

Don't you get weary

Walk together children

Don't you get weary

There's a great camp meeting in the Promised Land

Donna M. Cox

"From the moment of capture, through the treacherous middle passage, after the final sale and throughout life in North America, the experience of enslaved Africans who first arrived at Jamestown, Virginia...was characterized by loss, terror, and abuse."