Performance Practice

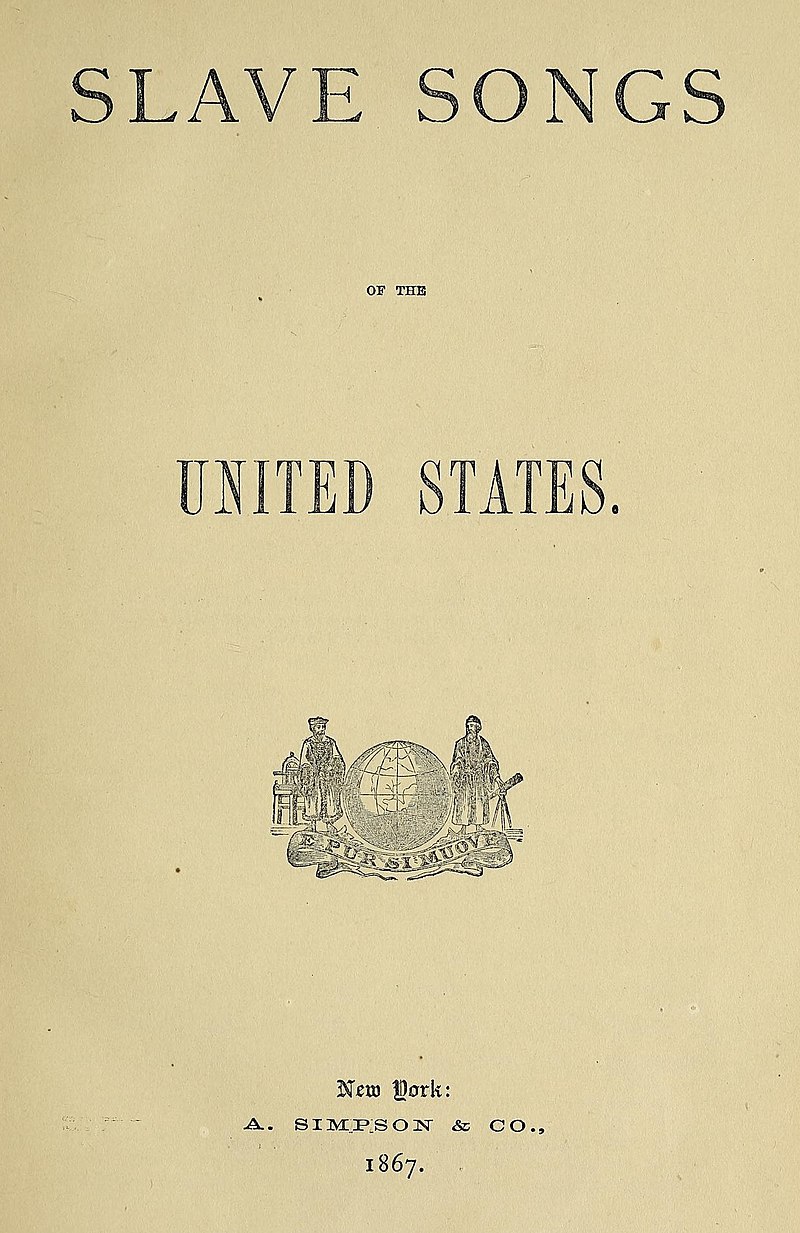

Nineteenth-century descriptions of indigenous African American religious music provide a glimpse of the overall character of how this music was performed. The label folk spiritual is useful to identify this genre as a product of the antebellum ![]() SIDE NOTEThe period before the Civil War, when slavery was still the law of the land. South. The descriptions included in the 1867 publication Slave Songs, a compilation of 136 songs, almost all of which are religious, is instructive.

SIDE NOTEThe period before the Civil War, when slavery was still the law of the land. South. The descriptions included in the 1867 publication Slave Songs, a compilation of 136 songs, almost all of which are religious, is instructive.

The compilers of this text-William Francis Allen, Charles Pickard Ware, and Lucy McKim Garrison-established unequivocally that folk spirituals were sung neither in unison nor in harmony. "There is no singing in parts as we understand it and yet no two [persons] appear to be singing the same thing" (Allen, Ware, and Garrison 1965 [1867], v). This heterophonic texture The simultaneous rendering of slightly different versions of the same melody by two or more performers. can be heard on the recording of "I Want to Go Where Jesus Is," made by the singing preacher and pastor Dr. C. J. Johnson (1913-1990). Although Johnson is a product of the twentieth century, William T. Dargan classifies Johnson's "singing style [as] rooted in the slave church" (Dargan 2006, 84).

Even though tempos were known to vary, folk spirituals had a characteristic regular pulse, with the text viewed as subservient to rhythm. Based on his personal observations, William Francis Allen notes, "The negroes [sic] keep exquisite time in singing and do not suffer themselves to be daunted by any obstacle in the words. The most obstinate Scripture phrases or snatches from hymns they will force to do duty with any tune they please" (Allen, Ware, and Garrison 1867, iv).

| Musical Textures Found in Music | |

|---|---|

|

|

As discussed earlier, the call-and-response or leader-chorus structure played a dominant role in antebellum spiritual performance practice. This specific structure juxtaposed short phrases sung by an individual with responses sung by the group. The constant repetition of the response allows and encourages everyone to participate, while variation was provided by the leader or soloist who was free to make textual, melodic, and rhythmic changes at will. In some instances, the soloist or leader ends the call before the response begins; in others, overlapping call-and-response results when the solo lead continues after the group response begins. One account offers this description: "… the leading singer starts the words of each verse, often improvising, and the others, who 'base' him, as it is called, strike in with the refrain, or even join in the solo, when the words are familiar" (Allen, Ware and Garrison 1965 [1867], v). Here is an example:

I Don't Feel Weary

CALL: I don't feel weary and no ways tired

RESPONSE: O glory hallelujah

CALL: Just let me in the kingdom while the

world is all on fire

RESPONSE: O glory hallelujah (ibid.,70).

The call-and-response form is a strong marker of the pervasiveness of African cultural memory in the lived experiences of New World slaves. Erich von Hornbostel, an African music scholar and pioneer in the field of ethnomusicologyEthnomusicology is the study of music from the cultural and social aspects of the people who make it. It encompasses distinct theoretical and methodical approaches that emphasize cultural, social, material, cognitive, biological, and other dimensions, or contexts of musical behavior, in addition to the sound., wrote in 1926 that call-and-response was a uniquely African characteristic of African American music. He conceded that call-and-response "occurs in European folksongsA song originating among the people of a country or area, passed by oral tradition from one singer or generation to the next., but in African songs it is almost the only one used" (quoted in Epstein 1983, 56-7).

Donna M. Cox

"From the moment of capture, through the treacherous middle passage, after the final sale and throughout life in North America, the experience of enslaved Africans who first arrived at Jamestown, Virginia...was characterized by loss, terror, and abuse."

Steal Away

O, walk together children

"Steal away

steal away

steal away to Jesus

Steal away

steal away home

I ain't got long to stay here"