Performance Practice (Continued)

In the New World, Black people encountered a European version of call-and-response A song structure of performance practice in which a singer or instrumentalist makes a musical statement that is answered by another soloist, instrumentalist, or group. The statement and answer sometimes overlap. Also called antiphony and call-and-response. in the practice of "lining out" often used in churches in which many of the congregation were illiterate. But the basis of lining out was the straight repetition by the congregation of a line of a hymn as lined out by the leader; it was, in effect, a sign of the leader's authority and did not involve the supporting and dialogical roles that collective response performed in African American worship. In his seminal work Lining Out the Word: Dr. Watts Hymn Singing in the Music of Black Americans (2006), William T. Dargan states that hymn lining is unaccompanied or a cappella singing in which a leader says or chants the words of the hymn to be sung and the congregation repeats singing the exact chants by the song leader which is an important extension of the call-and-response practice.

Mt Sinai Baptist Church- I Love The Lord, He Heard My Cry (Live Recording 8-19-2012) [ 00:00-00:00 ]

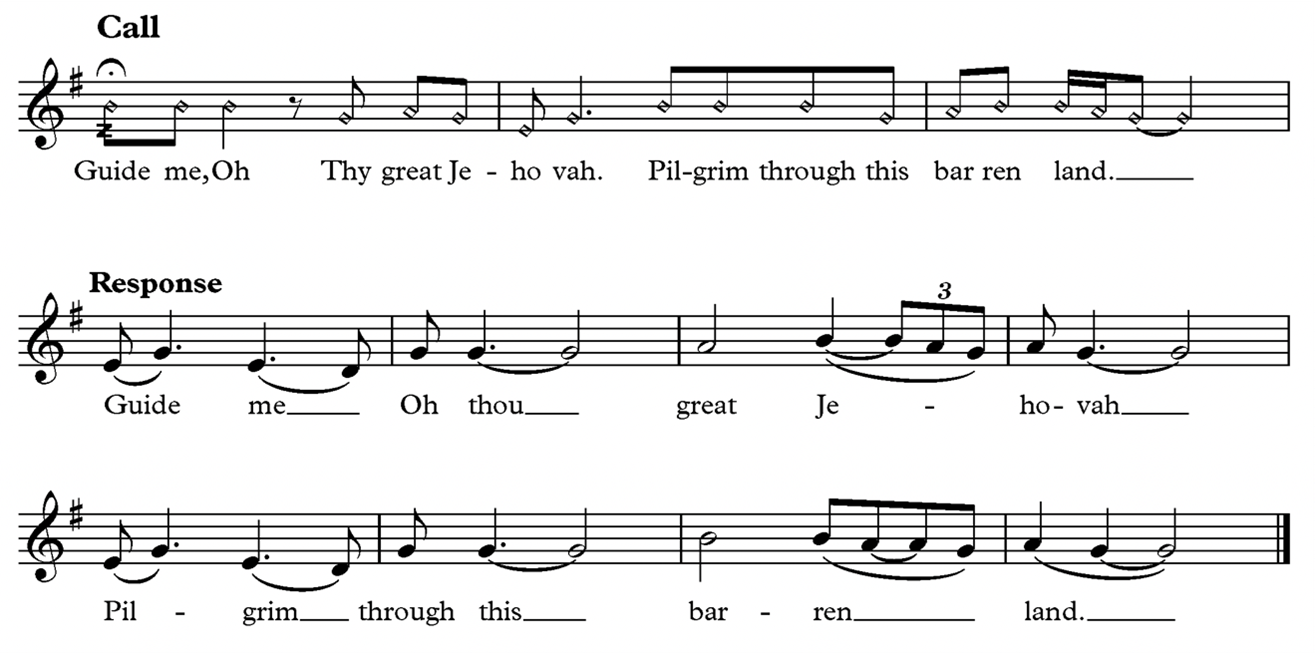

As seen in the example illustrated below the singer will chant the first section "Guide me, Oh Thy great Jehovah. Pilgrim through this barren land." This is then followed by the response of the call.

Other names for this type of singing include "Dr. Watts," "raise a hymn," "old one-hundreds," and the "old way of singing" (Dargan 2006, 26). In another seminal study, Black Culture and Black Consciousness (1977), Lawrence Levine has noted that "the overriding antiphonal structure of the spirituals … placed the individual in continual dialogue with his [sic] community, allowing him at one and the same time to preserve his voice as a distinct entity and to blend it with those of his fellows" (Levine 1977, 33).

Folk spirituals were typically accompanied only by handclaps and foot stomps, which complement the singing with a percussive timbral quality reminiscent of drumming. Bans on the use of loud musical instruments, especially drums, which could be used as signaling devices, did not succeed in eliminating the percussive dimension so highly valued in African music. Contemporary performances of spirituals by such groups as the McIntosh Shouters of the Georgia Sea Islands in which a broomstick is struck against a hardwood floor to replicate the sound of the drums are undocumented in nineteenth-century accounts (Rosenbaum and Buis 1998, 31).

In African American worship contexts, evidence suggests that creation and performance were inextricably connected. Levine brings together several graphic accounts of singing, some from the nineteenth century and some illustrating a continuity of practice in the South into the twentieth century, in which short phrases and exclamations, thrown back and forth by individuals and groups, engender what one observer calls a "creative thrill" (Levine 1977, 26). Another describes how, after one person at a prayer meeting calls out "Git right-sodger":

[i]nstantly the crowd took it up, moulding a melody out of half-formed familiar phrases based upon a spiritual tune, hummed here and there among the crowd. A distinct melodic outline became more and more prominent … Scraps of other words and tunes were flung into the medley … but the general trend was carried on by a deep undercurrent, which appeared to be stronger than the mind of any individual present.

(Levine 1977, 27)

Summing up, Levine remarks: "Created within this atmosphere, spirituals both during and after slavery were the product of an improvisational communal consciousness." They were, he goes on, "simultaneously the result of individual and mass creativity …," products of "that folk process which has been called 'communal re-creation,' through which older songs are constantly re-created into essentially new entities" (Levine 1977, 29).

Walk Together Children

O, walk together children

"Steal away

steal away

steal away to Jesus

Steal away

steal away home

I ain't got long to stay here"

Steal Away

"Steal away

steal away

steal away to Jesus

Steal away

steal away home

I ain't got long to stay here"