Spirituals: Based on Biblical Characters

But perhaps the greatest lyrical gift of the spirituals may have been their unknown composers' extraordinary ability to transform the heroes (and villains) of the Bible into a shared experience that not only taught theology but created universal literature, an ethical model, and a method of disseminating information as well as providing a precious few moments of respite and entertainment, and a source of comfort to the afflicted and abused.

Like virtually everything they accomplished, slaves took the scriptural scraps that their overseers gave them and refashioned them through the filter of their shared African memories into something new and powerful that sustained them as African Americans living in bondage.

Their radical new imaging of the Bible reflects the ethos of the first-century Christians’ (Followers of the Way) and strips away two thousand years of accumulated tradition. It is, therefore, one of the greatest gifts of the spirituals. These men and women knew Jesus of Nazareth on a personal level and lived in an ineffable now, believing every moment would see the return of the crucified Christ. For them, the giants of the Old Testament were just as real and vital as family members.

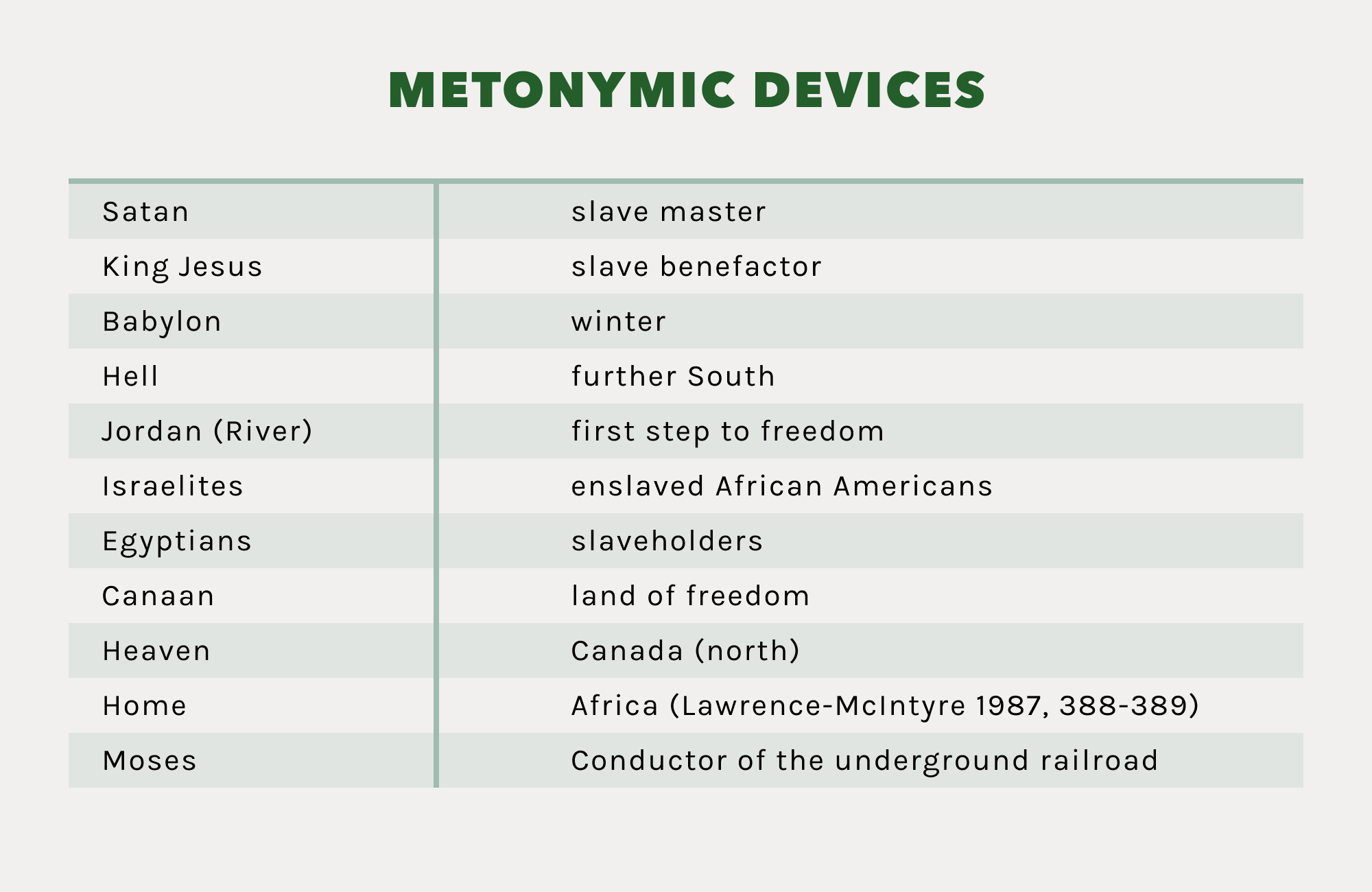

In the sprawling cast of Old and New Testament luminaries, slaves found stories and personalities expansive enough and rich enough to match the "traditional epic treatment" of their African ancestors (Lawrence-McIntyre 1987, 388). Charshee Charlotte Lawrence-McIntyre calls them "metonymic devices" 'Metaphors that allowed the African Americans to infuse the biblical figures and tales with additional layers of meaning decipherable only to the code-initiated slaves. Or put another way, a figure of speech consisting of the use of the name of one thing for that of another.—metaphors that allowed the African Americans to infuse the biblical figures and tales with additional layers of meaning decipherable only to the code-initiated slaves (Lawrence-McIntyre 1987, 388-389). Like Miles Mark Fisher, Lawrence-McIntyre asserts that many of the most common figures in the spirituals always carry this metonymic overlay:

"Satan is not a traditional Negro goblin," writes John Lovell, Jr., "he is the people who beat and cheat the slave. King Jesus is not just the abstract Christ, he is whoever helps the oppressed and disfranchised or gives him a right to his life. Babylon and Winter are slavery as it stands-note 'Oh de winter, de winter, de winter'll soon be over, children'; Hell is often being sold South, for which the sensitive Negro had the greatest horror. Jordan is the push to freedom" (Lovell 1939, 643-644).

But again, it is best not to definitively assign any specific trait or identification to any specific concept in the spirituals. When the creative geniuses who composed the spirituals dealt with the multifaceted personalities that populate the Christian Bible, they rarely restricted themselves to just a single interpretation of any biblical event or person. The slaves were intentional about their choice of subject for their songs. Otherwise intriguing personalities, such as the flawed, tragic, but ultimately heroic King Saul, rarely appear in the spirituals, nor do many of the twelve disciples, save for Peter. However, Old Testament figures such as Daniel, David, Joshua, Jonah, Moses, and Noah dominate the extant songs. According to Levine, this "Old Testament bias" is because of these men…

...were delivered in this world and delivered in ways which struck the imagination of the slaves. Over and over their songs dwelt upon the spectacle of the Red Sea opening to allow the Hebrew slaves to pass before inundating the mighty armies of the Pharaoh. They lingered delightedly upon the image of little David humbling the great Goliath with a stone-a pretechnological victory which postbellum Negroes were to expand upon in their songs of John Henry.

(Levine 1977, 50-51)

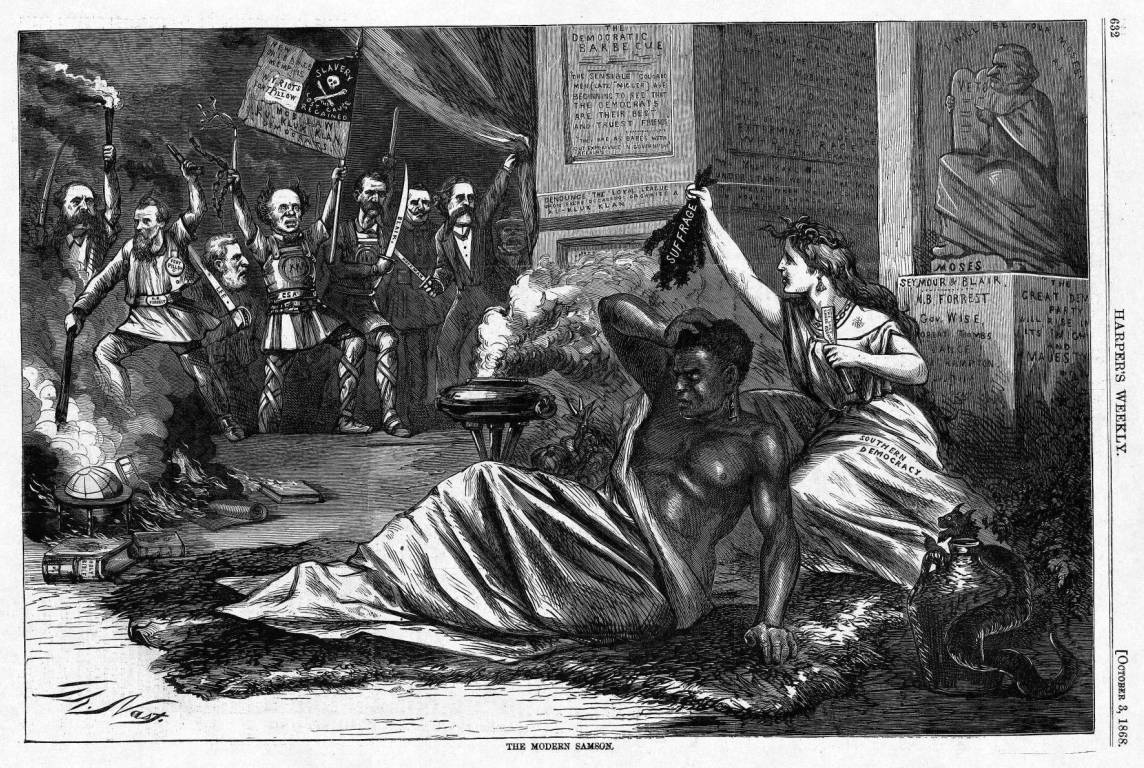

Some of their heroes, such as Samson, were obvious choices, blinded and in chains, toppling the palace of his captors (Levine 1977, 50-51). Others were more unlikely, such as the bewildered Noah ("Norah"), steadfastly building an ark, faithfully following the Lord's commands despite the ridicule of his neighbors:

Lyrics

Oh God comman' Brother Norah one day

Oh hist the windah let the dove come in

An tol' Brother Norah to build an ark

Hist the windah, let the dove come in

(Parrish 1942, 134)

And, over and over, the slaves told and retold the great stories of Moses and Daniel-Moses leading the Children of Israel out of bondage, Daniel delivered from the lion's den. "The similarity of these tales to the situation of the slaves was too clear for them not to see it," Levine adds, "[and] too clear for us to believe that the songs had no worldly content for Blacks in bondage" (Levine 1977, 51):

Lyrics

He delivered Daniel from de lion's den

Jonah from de belly ob de whale

And de Hebrew children from de fiery furnace

And why not every man?

Didn't My Lord Deliver Daniel

(Parrish 1942, 134)

What is nearly as remarkable is that the slaves' overseers didn't hear the obvious notes of rebellion in these songs. But then, to admit the spirituals were something other than gibberish or nursery school rhymes would have demolished their carefully constructed mythology that African Americans were subhuman. Following the Nat Turner revolt, a delegate to the Virginia legislature once boasted, "We have as far as possible closed every avenue by which light may enter slaves' minds. If we could extinguish a capacity to see the light our work would be completed; they would then be on a level with the beasts of the field" (Ames 1955, 143-143). Consequently, the slaves sang inflammatory spirituals like this one, within earshot of their masters, at every turn:

Lyrics

Then Moses said to Israel

When they stood upon the shore,

"Your enemies you see today,

You'll never see no more. "

Then down came the raging Pharaoh,

And you may plainly see,

Old Pharaoh and his host

Got lost in the Red Sea.

Didn't old Pharaoh get lost, get lost

Didn't old Pharaoh get lost in the Red Sea?

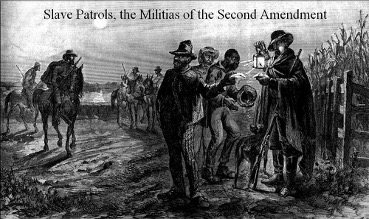

Slave Patrols

Source: AEsquibel23

"It is hardly possible that the slaves made no connection between themselves and the Israelite slaves. Indeed, the escape of the Israelites and the destruction of Pharaoh's 'patter-rollers' was repeatedly described in Negro spirituals, while their whole enslaved people was referred to as 'my army'"(Ames 1955, 143).

"Patter-rollers," "pater-rollers," or "padder-rollers" were the feared white vigilantes or "patrol officers" who roamed the Southern countryside at night, empowered by custom or legal precedent to apprehend, punish, and return any slaves they encountered.

Booker T. Washington

The plantation songs known as "Spirituals" are the spontaneous outburst of intense religious fervor. They breathe a child-like faith in a personal Father, and glow with the hope that the children of bondage will ultimately pass out of the wilderness of slavery into the land of freedom.

Go Down, Moses

Dark and thorny is de pathway

Where de pilgrim makes his ways;

But beyond dis vale of sorrow

Lie de fields of endless days.