Spirituals: Personal Religious Testimony and Experience (Continued)

To the slave, space and time were irrelevant, as it was to the Renaissance painters who placed fifteenth-century garb on Christ and the Apostles. "There was an immediacy about their relationship to biblical persons which allowed for intimacy in the midst of estrangement," writes Dixon. Slaves didn't sing about David; they sang to David: "Lil David, play on yo' harp, Hallelu, hallelu" (Dixon 1976, 2-3). Lawrence Levine calls it "sacred time," an understanding of the infinite now that enabled slaves to equate President Abraham Lincoln with Father Abraham and Harriet Tubman with Moses in a place where past, present, and future are all one. The slave witnesses Christ being crucified-"It causes me to tremble," even now (Levine 1977, 31). As one writer put it, "Another remarkable quality of Negro spirituals . . . is their immediacy-the sense that biblical history is taking place right before your eyes or even that you are included in the action" (Ames 1955, 135-136).

"For the slaves, then, songs of God and the mythic heroes of their religion were not confined to a specific time or place, but were appropriate to almost every situation" (Levine 1977, 31). Time extends upward to allow communication with God. It also extends downward to allow the archetypal ancestors to be continually reenacted and recovered at the same time-sacred time. "For the slaves, then, songs of God and the mythic heroes of their religion were not confined to a specific time or place but were appropriate to almost every situation" (Levine 1977, 31).

This timelessness enabled the slaves to soar beyond their chains and inextricably tie their lives to the lives of the biblical saints and with John the Revelator's vision of the heavenly kingdom to come. "The spirituals are the record of a people who found the status, the harmony, the values, the order they needed to survive by internally creating an expanded universe, by literally willing themselves re-born," writes Levine (Levine 1977, 33).

The spirituals were thus essential in creating a shared consciousness-and a shared community. All shared in the passion of Christ; all crossed the Red Sea with Moses; all looked to be free-be it in heaven or Canada-together.

"Standing the storms of life as a group is much easier than standing them individual by individual," declares John Lovell, Jr.

The slave poet and all his singers knew that the breaking down of the group morale of the slaves was considered to be a necessity of the governing classes. If the master and the overseer could handle them one by one, they could inflict upon them all any kind of discipline. But if they held together as a group, their resistance would be hard to overcome. Thus they sang:

We'll stand the storm

It won't be long

We'll anchor by and by

(Lovell 1972, 276)

And if they do "stand the storm," something extraordinary happens. Lovell believes that the "really significant poetry" is found in the spirituals that celebrate heaven:

Take a simple spiritual like "I Got Shoes." "When I get to heav'm" means when I get free. It is a Walt Whitman "I," meaning any slave, present or future. If I personally don't, my children or grandchildren, or my friend on the other end of the plantation will. What a glorious sigh these people breathed when one of their group slipped through to freedom! What a tragic intensity they felt when one was shot down trying to escape!

So, the group-mind speaks in the group way, all for one, one for all. "When I get to heav'm, gonna put on my shoes . . ." that means he has talents, abilities, programs manufactured, ready to wear. On [Frederick] Douglass' plantation, the slaves bossed, directed, charted everything-horse-shoeing, cart-mending, plow-repairing, coopering, grinding, weaving, "all completely done by slaves." But he has much finer shoes than that which he has no chance to wear. He does not mean he will outgrow work, but simply that he will make his work count for something, which slavery prevents. When he gets a chance, he says, he is going to "shout all ober God's heav'm"-make every section of his community feel his power. He knows he can do it.

(Lovell 1939, 641-642)

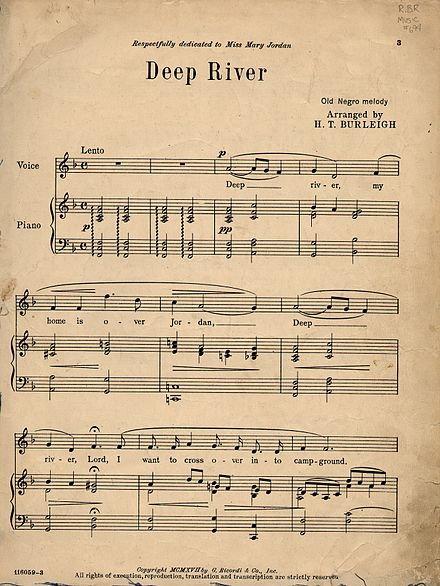

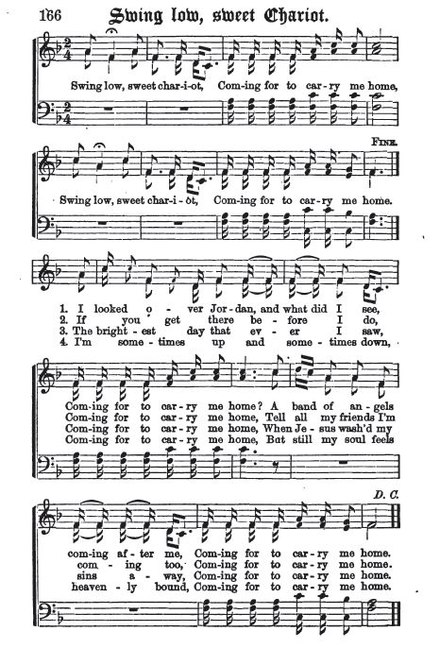

There are many more spirituals, thousands more. There are spirituals celebrated for their melody's haunting beauty: " Deep River " and " Swing Low, Sweet Chariot ." There are spirituals celebrated for the quiet power of their words: "Lay This Body Down" ("I walk in de moonlight, I walk in de starlight, I lay dis body down. I know de graveyard, I know de graveyard, When I lay dis body down."). And there are epic spirituals with dozens, perhaps hundreds of verses that tell the story of not just one nation, but two: " Go Down, Moses ."

In summation, Lovell makes a thoughtful observation:

The Negro slave is the largest homogenous group in a melting-pot America. He analyzed and synthesized his life in his songs and sayings. In hundreds of songs called spirituals, he produced an epic cycle; and, as in every such instance, he concealed there his deepest thoughts and ideas, his hard-finished plans and hopes and dreams. The exploration of these songs for their social truths presents a tremendous problem. It must be done, for, as in the kernel of the Iliad lies the genius of the Greeks, so in the kernel of the spiritual lies the genius of the American Negro .

(Lovell 1939, 642-643)

Howard Thurman

For [the slaves] the 'troubled waters' meant the ups and downs, the vicissitudes of life. Within the context of the 'troubled' waters of life there are healing waters, because God is in the midst of the turmoil. Do not shrink from moving confidently out into the choppy seas. Wade in the water, because God is troubling the water.

Booker T. Washington

The plantation songs known as "Spirituals" are the spontaneous outburst of intense religious fervor. They breathe a child-like faith in a personal Father, and glow with the hope that the children of bondage will ultimately pass out of the wilderness of slavery into the land of freedom.