Spirituals: Definitive Form

Though it may be tempting to do so, although certain spirituals share some common characteristics, there is little point in attempting to uncover the definitive form of a spiritual. The spirituals contain some of the greatest, most evocative religious poetry of all time, but they were also part of the greater African American slave communications system, an extraordinarily complex secret language that enabled these brutally oppressed people to survive and flourish.

And, as John Storm Roberts continually cautions, just because a certain spiritual was captured on a single plantation in 1863 does not mean that it is the definitive form of that spiritual-if, indeed, a "definitive" form exists. Most transcribed spirituals were little more than snapshots (Roberts 1972, 170)-in fact, a transcription might only have captured the first or the last known performance of a given spiritual. In the years to come, that spiritual's melody and lyrics might change until it becomes unrecognizable to the congregation where it first appeared.

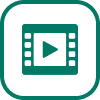

Concerning the dating of spirituals, it is possible to date some within a few decades, especially those referring to specific people or events. For instance, the first modern railroad appeared in the United States in the late 1820s, and no railroad lines made it into the Deep South until the 1830s and 1840s. Both slaves and masters alike shared a fascination with the sound, speed, and power of the new "iron horses." Therefore, even though few slaves were hardly ever allowed a free run on a train, spirituals such as "Git on Board, Little Children" (also called " The Gospel Train "), "Same Train ," " When the Train Comes Along ," " How Long de Train Been Gone ," must be later than this period (Lovell 1972, 249). The words to "Git on Board, Little Children" have a particularly poignant quality and may reference the Underground Railroad as well:

Lyrics

De fare is cheap, an' all can go, De rich an' poor are dere, No second class aboard dis train, No differunce in de fare.

Spirituals: Meaning of the Text

Equally perilous is to assign definite meaning to the words of a given spiritual. The informed listener would be on much safer ground assuming that many of the surviving spirituals may have had multiple layers of meaning, and admitting that certain spirituals are inspired-or, as the Holiness preachers might say, anointed.

"It is highly significant that with all the biblical characters, incidents, parables, sermons, and historical features to choose from, the slave, in thousands of songs, selected relatively few and turned these to only a few ends," John Lovell, Jr., writes. "The secret of his genius was in the skill of his adaptations, not in the volume of his selections. He could take the same character or incident and give it many dazzling facets. He was more interested in genial touches than in serious sermonizing. His sense of the grotesque or humorous and his comparisons of some Bible personality with ridiculous or hidden aspects of his own world were often the key to his final treatment" (Lovell 1972, 257).

To understand spirituals, the reader or singer is best served by understanding the language of the slaves who sang them. In Black Song: The Forge and the Flame, Lovell, who takes the position of understanding culture from the emic ![]() SIDE NOTEAn emic view of culture is ultimately a perspective focus on the intrinsic cultural distinctions that are meaningful to the members of a given society, often considered to be an 'insider's' perspective.

SIDE NOTEAn emic view of culture is ultimately a perspective focus on the intrinsic cultural distinctions that are meaningful to the members of a given society, often considered to be an 'insider's' perspective.

For more information click on link here -insider-perspective, (Lumen, n.p.) reminds us that no one not born and reared in a particular folk community can understand the significance of that community's folk songs. It does not mean we can't sing or appreciate or study them-but we'll always be looking through a glass, darkly (Lovell 1972, 137).

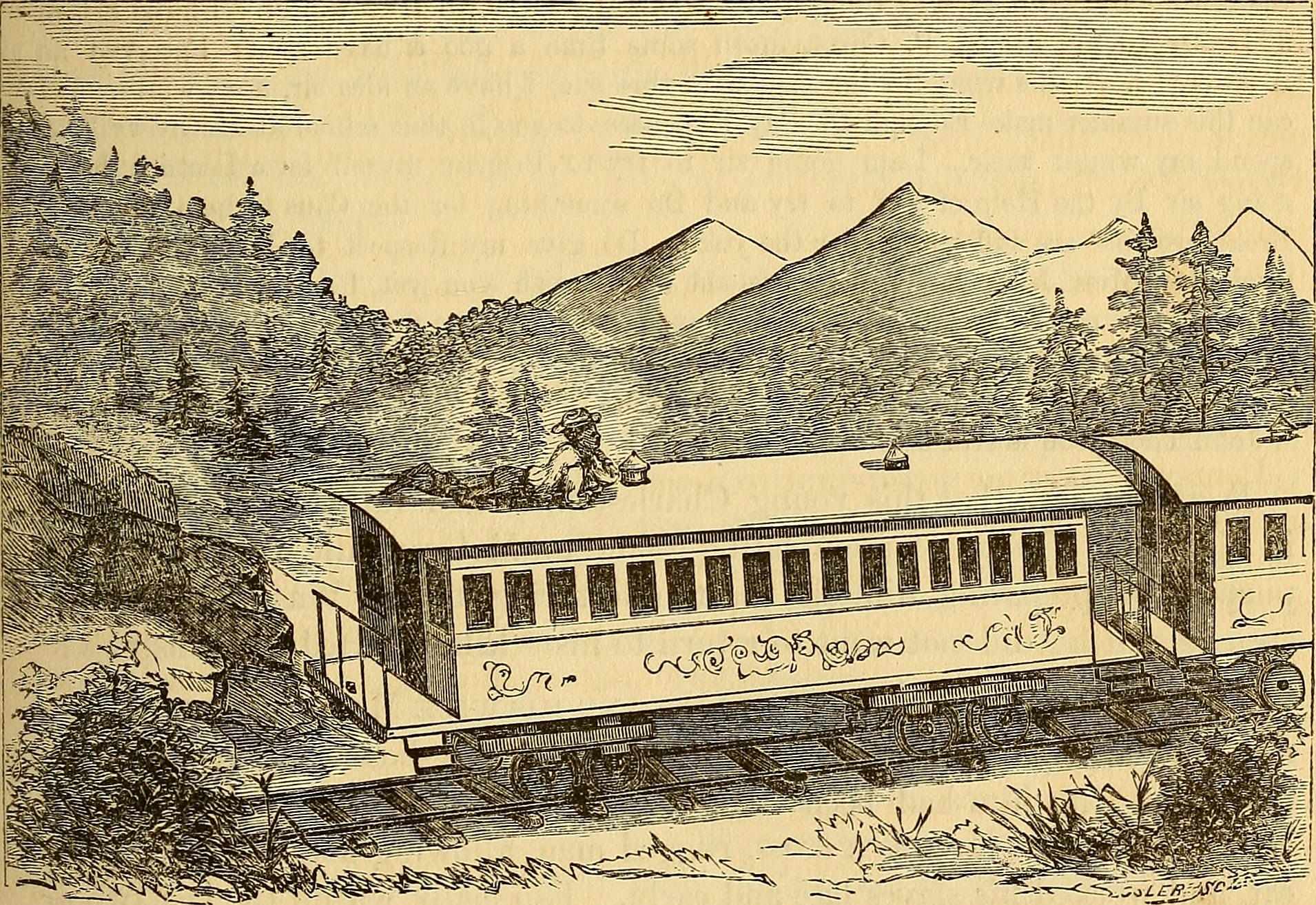

The language established by enslaved African Americans was a colorful blend of African syntactical features and words-carefully created "code" words-and the dialect that resulted from generations of illiterate slaved people taught only the barest necessities of spoken English. This code made communication between enslaved groups easier and served to effectively conceal African American goals and dreams. Out of direst necessity, it spread to the Black Church as well (Holt 1972, 189-190). "Even today," writes Holt, "a White person visiting a rural or ghetto church might find it difficult if not impossible to decipher or interpret the 'code' talk of the preacher" (Holt 1972, 189-190). And with the spirituals, slaves were able to create a wonderfully effective "clandestine theology," (Steward 1983, x) using that code to outsmart their captors.

Go Down, Moses

Dark and thorny is de pathway

Where de pilgrim makes his ways;

But beyond dis vale of sorrow

Lie de fields of endless days.

Booker T. Washington

The plantation songs known as "Spirituals" are the spontaneous outburst of intense religious fervor. They breathe a child-like faith in a personal Father, and glow with the hope that the children of bondage will ultimately pass out of the wilderness of slavery into the land of freedom.