The Invisible Church

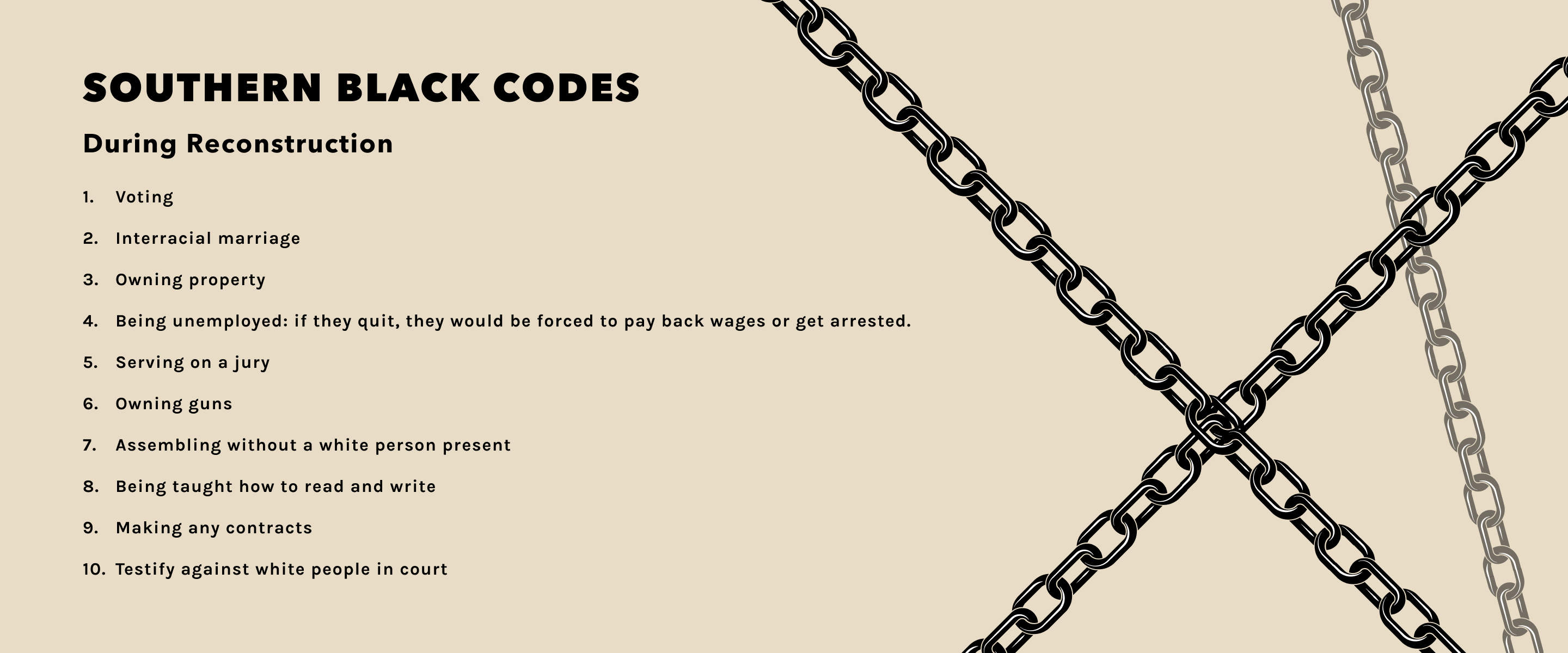

Whether in the ravine, field, or living quarters, African American slaves fiercely guarded their religious privacy, not merely out of fear of reprisal, but out of their collective desire to express themselves in a way that was most meaningful to them. Although Black codes A body of laws, statutes, and rules enacted by southern states immediately after the Civil War to regain control over the freed slaves, maintain white supremacy, and ensure the continued supply of cheap labor. prohibiting the assembly of Black people outside the presence of White people were passed in Virginia as early as the 1630s, slaves nonetheless chose to risk life and limb to engage in autonomous Christian worship (Harding 1981, 27). In churches and camp meetings, Black people learned the language of Protestant Christianity, absorbed the events and images of the Bible, and became familiar with hymn singing as a particular way of expressing a collective response to God.

But the actual creation and performance of songs now identified as spirituals appear to have occurred in autonomous contexts, where they were able to articulate a self-defined concept of music and worship.In the South, the invisible church clandestine gatherings in spaces designated for purposes other than worship-was the spawning ground; in the North, it was the independent Black church. Whether in the ravine, field, or living quarters, African American slaves fiercely guarded their religious privacy, not merely out of fear of reprisal, but out of their collective desire to express themselves in a way that was most meaningful to them.

Although Black codes A body of laws, statutes, and rules enacted by southern states immediately after the Civil War to regain control over the freed slaves, maintain white supremacy, and ensure the continued supply of cheap labor. prohibiting the assembly of Black people outside the presence of White people were passed in Virginia as early as the 1630s, slaves nonetheless chose to risk life and limb to engage in autonomous Christian worship (Harding 1981, 27).

Former slave Alice Sewell recalls, "We used to slip off in de woods in de old slave days on Sunday evening way down in de swamps to sing and pray to our own liking" (Yetman 1970, 263). Similarly, Fannie Moore recalled her experience of slavery, stating, "Never have any church. If you go, you set in de back of de white folk's church. But de niggers slip off and pray and hold prayer-meetin' in de woods, den dey turn down a big wash pot and 'member some of de songs we used to sing" (ibid., 229).

The character of worship among Blacks in the invisible church was closely related to that of contemporary African American worship. There was prayer, communal singing, testifying, and sometimes, but not always, preaching. The most striking aspects of worship were evident in the way these elements were expressed. Prayer was extemporaneous, typically moving from speech to song. Congregational participation, in the form of verbal affirmations, was not only accepted but expected, and highly valued. Singing involved everyone present and was accompanied by handclapping, body movement, and, if the spirit was particularly high, shouting (the term refers to an altered state not to be confused with the danced form of the spiritual referred to as the ring shout discussed in Unit 1, Lesson 3) and religious dance, both peak forms of expressive behavior.

Ecstatic worship, in which participants expressed themselves through altered states, was commonplace in the invisible church. Under the influence of the Holy Spirit, congregants could be moved to scream, fall to the ground, run, cry, or dance. When worshippers were particularly engaged, services sometimes lasted far into the night, the length being determined only by the collective energy that fueled the group (Raboteau 1978, 220-2).

The key characteristics of these sacred spaces, which were vitally important to the enslaved community, are shown below and are consistent with the many accounts by ex-slaves from this period:

- The importance of private, divine space where freedom could be sought and experienced

- Ownership of a Christian belief system and code of religion that they could call their own

- The uncomplicated manner of worship, conducted in the way of the people without outside interference

- The divinely inspired, minimally educated but biblically articulate preachers, called from among the plantation folks, with a sensitivity to the plight of their people

- Freedom of the spirit to enable the preaching, singing, praying, shouting, and responsive listening of the Spirit-filled congregations.

- Freedom to worship at a time determined by the slaves themselves

- Mutual community affinity where "everybody's heart was in tune, so when they called on God, they made heaven ring

- With the support of the community, slaves could experience and be sustained with new life and move with hope into the future (Raboteau 1978, 216)

While the Scripture-inspired message of the spiritual was clearly religious, this fact did not preclude from its singing in nonreligious contexts. Whether encouraged by slave owners to sing while working, or opting to do so of their own volition, the message of spirituals remained constant. God was aware of the slave's daily suffering, and God could deliver them in time, just as he had done for Daniel, Moses, Joshua, and many other biblical characters of the Old Testament, as shown in figure 5.2. Sometimes spirituals conveyed slaves' desire for freedom, as in the double entendreSong text with double meaning. text recorded by the Seniorlites of John's Island, South Carolina, on the anthology album Wade in the Water

the singers successfully masked their rage with the manifest image of death, safely deceiving the slave holder into believing that his docile and passive slaves were again dreaming of heaven but thankfully loyal in the present to his unrelenting demands for service. Skillfully, the singers affirmed their inner loyalty to a legitimate, heavenly master, but also announced their determination to take up arms against the earthly master

(Jones 1993, 57)

| Selected Song Texts with Imagery Taken from the Old and New Testament | |

|---|---|

| Old Testament | New Testament |