Pow-wows: Southern and Northern (Continued)

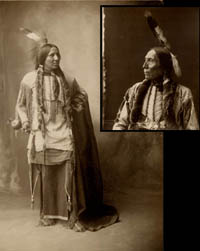

Kiowa woman and chief, 1868

The established formal structure of pow-wow music has remained unchanged for almost half a century. This form, most often termed "incomplete repetition" by scholars has distinct Northern and Southern variations. In Oklahoma, when the Omaha Heluska Warrior Society was taken up by the Comanche and Kiowa, they referred to its music and dances as "O'ho-ma," most likely a mispronunciation of Omaha.

Although the Kiowa and Comanche spread the Warrior Society from tribe to tribe, the geographical distance between tribal groups in Oklahoma was much less than in the North, which resulted in fewer deviation from the original Heluska (He'thu'shka) style. Also, the Oklahoma Ponca share the same language and music with the Omaha.

Until the 1860s the Ponca were part of the greater Omaha nation, and have been influential in maintaining Heluska songs in the South. Half of Native Americans live within ten states. In 2000, the states with the largest Native American populations were California, Oklahoma, Arizona, Texas, and New Mexico. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the Native American population in Oklahoma grew from 8.6 percent in 2010 to 8.9 percent in 2011.

Pow-wow songs are in a repetitive strophic (verse) form, which serve as flexible yet codified framework for new song creation. Plains pow-wow music uses an AA' BC BC form, with each phrase grouping ending with a formulaic cadential pattern of genre-specific vocables. This "Omaha" form (named after its originators) traditionally repeats four times, with three drum accents called "hard beats" between the two BC phrase groupings in the Southern Plains style, and four to five "honor beats" within the interior of a BC phrase grouping in the Northern. In general, Southern singing has slower tempos (with the exception of fancy-dance songs), more flowing vocal lines, and softer dynamic levels, while Northern musicians tend toward faster tempos and more active rhythmic structures. Northern songs are also sound louder to the listener, but this is probably because the higher notes in the melodies and tighter vocal production style of the singers combine for greater sound projection.

Songs come in a variety of categories defined whether or not the song has a steady two-beat or three-beat pattern, and its function within the event. Songs organized in steady two-beat patterns are derived from the old Heluska war songs, and are used for general intertribal dancing and competition. Three-beat pattern songs, with the actual drum-beats on one and three, are social dance songs for "round-dance" or "two-step" categories. Songs with a series of single accented drum-beats are for "Crow-Hop" (Northern) or "Horse-Stealing" (Southern) dances.

Women's Traditional Dancer (l)and Jingle Dress Dancer (r)

pow-wow dance styles in urban areas and outside of the Plains regions tend toward the generic, with personal interpretation of the various categories (Traditional, Fancy, Grass, and Jingle). The spread of competition pow-wows offering large prize monies, where "different" is frequently equated with "better," escalates the rate of change in dance and regalia styles, especially at urban events. This kind of adaptation of older customs to fit with newer societal trends is called recontextualization, and in the case of pow-wows describes the way that older forms such as pow-wow music and traditional dancing can survive and prosper in the same cultural venue that allows male Fancy dancers to perform cartwheels and splits as part of their routines.

In recent years Southern pow-wows have become hosts to sessions of Gourd Dancing, a recontextualized celebration of the music and dance of the Kiowa Tiah-pah Warrior Society (also known as the Gourd Clan), and a strong conservative influence on musical tradition.

Although the process of recontextualization may seem threatening to those outside of the pow-wow community, native people know that their elders will make sure that older forms of songs and dances are preserved for the younger generations, invigorating the pow-wow arena with infusions of tradition.

Harry Buffalohead, Ponca singer

In Native American cultures, the roles of music and dance are connected with ceremonial rituals.