Conclusion: Chinese Music in the Global Market

This chapter aims to grasp the whole landscape of Chinese music, from traditional to modern, from elite to popular, from court to folk, from secular to sacred, from vocal to instruments, from solos to ensembles, from Han to relatively less populated ethnic groups, from local traditions to imported ones, from regional to national traditions, and from traditional music to pop music or to newly 'invented' music for traditional instruments. Inevitably, the contents are fragmental: Chinese music is a huge topic, involving the cultural expressions of around a quarter of mankind. However, taken altogether, the contents will hopefully succeed in conveying for readers a sense of the richness and variety of the music making that sits under the collective title 'Chinese music'.

In closing, it's important to consider a few questions regarding current trends in this large, diverse field: What expectations, cross-references, or oppositions are set up, spoken or unspoken, when we adopt this category? What is the attitude of contemporary Chinese musicians toward musical or cultural authenticity? How do they react to an increasingly globalized world, and how do these expectations differ from one genre or musical perspective to another?

Composer Guo Wenjing is one musician who has commented on the challenges of the 'Chinese' composer (Example 20: Interview with Guo Wenijing) label: 'I don't know what a Chinese composer should be. No one can regulate what Chinese music should be. Any pre-design of what is or is not Chinese will be wrong. My purpose is to create, and I feel that there's ground beneath my feet. Even if the Chinese people don't accept me, my compositions are still part of Chinese culture-or at least a part of contemporary Chinese life-simply because I live in China.'

Chinese Classical Music: Interview Guo Wenjing [ 00:00-00:00 ]

Contemporary Chinese composers' position in the global market extends well beyond China's borders, but still refers back to its historical past. Among them, Tan Dun (b. 1957) is an influential figure. His music for the film 'Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon', definitely planned to appeal to the international viewers at whom the film was partially aimed, featured the internationally prominent cello player Yo-Yo Ma (Ma Youyou) as a soloist. Meanwhile, the female composer Kuang Haoyue, although less-known, is a good representative of the currently diversified and fragmented Chinese culture. She has written several film music compositions for the American market, including the song 'Chang An Street' in the TV series 'The Mentalist' in 2012, and more recently 'Lotus Garden Sunset' (Example 21: Sung by Kuang Haoyue. Firstcom Music) in the film 'I Feel Pretty' (personal communication with Kuang Haoyue, July 2018). By incorporating Chinese instruments, melodic development, and form, both songs clearly suggest Chinese music tradition, but at the same time display a mixture of 'exotic' flavor and 'universal aesthetics' that lends them a modern sound in the international market context.

Composer: 0

-

"Kuang Haoyue - Lotus Garden Sunset"

Approaches to musical fusion vary from the perspective of genre as well as audience. Even though Chinese popular music today embraces global tendencies and exhibits stylistic syncretism, it is aimed primarily at Chinese audiences and therefore doesn't necessarily share similar characteristics with the pop music of other areas of the world. For instance, the recent pop song 'Going Up the Mountain, Coming Down the Mountain' ('Shang shan xia shan'), which won the TV music contest The Song of China in 2016, claims to present the unique culture of 'exotic' ethnic life styles as found among ethnic minority groups in Guizhou and Yunnan provinces. This is shown in the singer-songwriters' costumes; the adding of passages in local dialect; the use of ethnic instruments like the lusheng (bamboo reed-pipe mouth organ), big drum, yueqin (moon-lute), and kouxian (Jew's harp); the inclusion of group singing in unison; the combination of vocal styles including repetitive recitation interspersed with long-duration calls (that elicits in the Chinese mind the so-called mountain song, shan'ge, introduced in the section on 'folk song' above); and a ritualistic ending that imitates the proposing of a toast by an ethnic minority group. Alongside these ethnicity markers are 'universal pop aesthetics' consisting of rhythms, instrumentation, vocal style, language, and elements of rock and rap. In addition to a very neat and energetic rhythm section audible through the whole piece, there's an electric band with guitar and bass, and a large-scale string ensemble. The lyrics of the song make reference to daily life activities of ethnic minority communities; summon up heroic models of manhood typically seen in classic novels like Outlaws of the Marsh; evoke common tropes from Chinese traditional philosophy ('going up and going down the mountain, going up is for going down, going down is for going up'); and cite the classic Bai jia xing (a historical compendium listing the hundred Chinese surnames). The song's main language is Mandarin Chinese, featured prominently in the middle section where the hundred surnames of the Bai jia xing are rapped out one by one (Qian 2017).

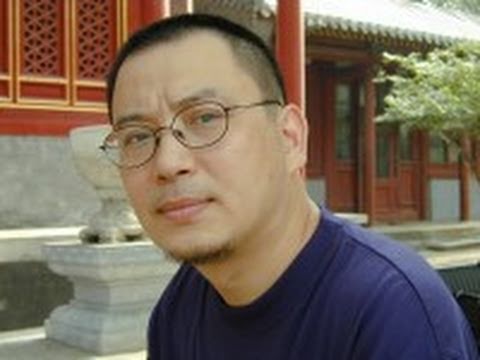

Nor are these new hybrids confined to the worlds of concert music or pop. Another example concerns the peacock drum. This newly invented drum is a creation based on the prestigious elephant foot drum tradition that once played a vital role in local Dai people's lives in Yunnan province, now on the edge of extinction. Meanwhile, drums imported from Africa have become popular in Yunnan's urban settings and are on sale in many instrument shops. Many people prefer the African drums because of their timbral variety, their conveniently portable sizes, and the perceived match between the skills required to play on these imported instruments and people's current musical aesthetics. To tackle this situation, a group of musicians led by Wang Fengli and her daughter Liu Xiaoyao (Figure 17) from the Yunnan Arts Academy, have transformed the elephant foot drum into a new peacock drum of their own creation.

They have kept the original shape and unique sound quality of the elephant foot drum, but increased its physical resonance, volume, and register, thus allowing for a wider range of performing techniques. This new peacock drum is painted to recall the traditional beliefs and patterns of several distinct ethnicities in Yunnan province-not only the Dai-and thereby points towards an all-inclusive kind of pan-ethnic aesthetics. Fengli's invention has been welcomed by tutors in schools and universities in Yunnan, who are reportedly happy to find an instrument that attracts their students from a musical perspective while strongly referring to their own 'traditions' (Example 22: Personal communication with Wang Fengli and Liu Xiaoyao, May and June 2018).

Example 22: Peacock Drum Performance

China is a large and varied region, with distinctive peoples and ways of life, as well as important and widely shared cultural traditions. This chapter's goal has been to present an overview of its extensive historical traditions, while giving a glimpse of its vibrant role as a center for new musical creativity in the global context.

Linguistic tone is crucial to understanding spoken Chinese: the sound 'da' could mean either 'big' or 'to beat' (among other meanings) depending on its pitch and contour.