Spirituality and Class Distinctions

From ancient rock carvings of hunting rituals and fertility dances to the high-tech existence of today, Koreans have found musical inspiration in their reverence for the world of the spirits. Musical performance was not merely an act of entertainment but tied to their spiritual and survival needs. Ancient Chosôn, the first Korean kingdom, was founded in 2333 BC in what is today the northeastern province of Liaoning of China, Manchuria, and the northwestern territories of the Korean peninsula.

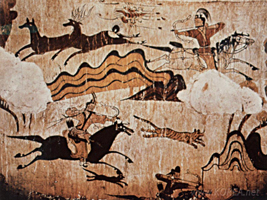

Kokuryo Tomb

Around the fifth century BCE, many more tribal kingdoms emerged as the old kingdom was disintegrating: Puyô, Okchô, Tongye in the plains of Manchuria, and Mahan, Chinhan, and Pyônhan in the south. Each celebrated hunting, farming, and harvesting by involving the entire nation with singing, dancing, and drumming such as yônggo, a spirit welcoming drum festival of Puyô during the night of the first full moon.

From the first century BC, the tribal states regrouped into four distinct kingdoms:

- Koguryô (37BC-668 AD) in the north

- Paekche (18BC-660AD) succeeded by Mahan

- Kaya (43-562AD)[4]One of numerous historical revisions the Japan made to help legitimize their territorial aggression during the Japanese colonial era (1910-1945). Some Japanese historians continue to assert Kaya was Japan's colony. from Pyônhan

- Silla (57BC-935AD) from Chinhan

It is known that political rulers were spiritual leaders simultaneously, and musical performance was typically the medium of communication between this world and the netherworld. It was therefore necessary for the masters of religious ceremonies to be affiliated with music, and musical performance developed in close connection with religious ceremonies. In Silla, leaders were first groomed as hwarang, the "flower youths," who were trained in music, poetry, dance, ritual ceremonies as well as the affairs of the nation and martial prowess. Where religion and music were so connected, songs and instruments, too, were believed to possess spiritual power. The Song of Ch´ôyong is a good example:

THE SONG OF CH´ÔYONGThe seventh son of the Dragon King of the East Sea, Ch´ôyong was married to a dazzling beauty and residing in Silla. One night he returned home to find his wife in bed with another man, and Ch´ôyong danced to expel the evil spirit of the adulterer. Ch´ôyong´s gentle virtue was overpowering and the adulterer revealed himself and asked for forgiveness. Ch´ôyong´s dance became the ritualistic way evil spirits were cleansed from the Korean court before each new year began.

From the fourth century, the musical cultures of Central Asia, along with Buddhism, entered Korea, catalyzing active musical exchanges between Korea and her neighbors. The music, dances, and instruments of Koguryô, Paekche, Silla, and Kaya were transmitted to Japan to influence and be adopted into the Japanese court music and mask dance repertoires.[5]"Korean Traditional Music, Vol. 1, 16-29." Two zithers invented during the era attest to the musical convergences and divergences in East Asia happening at the time. The 21-string kayagûm, a zither from Kaya, finds similarities with the Japanese koto, Chinese guzheng, and Vietnamese đàn tranh.

The 6-string kômun´go is known to have been modified by the Koguryô minister Wang Sanak from a seven-string zither introduced from the Jin kingdom. Legend has it that when he played, black cranes flew in and danced to the music, thus the name kômun´go, "black crane zither."

|

Lyrics

|

|

Seoul, bright moon,

Into the night deep I was carousing, Back home and in my bed, I see four legs! Two are mine, And the other two? The two are mine indeed but, They’re taken, so what could I do?[6]"Recorded in Samguk yusa (Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms), translated by Chan E. Park." |

| Translation by Chan E. Park. |

Originally a vocal music piece commemorating Buddha´s historic exposition of the Lotus Sutra on Vulture Peak Mountain (Yôngch´wisan in Korean)[7]"Korean Cultural Heritage Volume III: Performing Arts, Korea Foundation, 1997: 38.", yôngsan hoesang in later Chosôn developed into a complex instrumental composition of varying rhythmic and melodic structures. It starts with sangyôngsan, the slowest cycle of 20 beats with accentuation on the first (ttông!), seventh (ttôk!), eleventh (kung!), and fifteenth and sixteenth beats (ttôrôrôrô—dôk!) on a ch´anggo, the Korean hourglass.

Listen to garakdeori, another cycle within yôngsan hoesang:

Composer: 0

-

"Garakdeori solo"

A combination of exorcism and entertainment, festivals called narye were held at the Koryô court featuring ritual performance, acrobatics, music, and dramatic skits, and continued into the Chosôn royal household. Chosôn distanced itself from Buddhism and adopted the Neo-Confucian political ideologies and social mores that placed music and performing arts, especially of folk origins, at the bottom of the social hierarchy. As a result, Korean folk rituals, performing arts, and artists fell to an outcast existence. Categorized as kwangdae (male performer), kisaeng (female performer), and mudang (mistress of shamanic ritual) or paksu (master of shamanic ritual, much smaller in number than female), the performing artists and spiritual healers were left to forge close artistic and familial kinships among themselves.

As you can see, although most shamans were mostly female, there were some male practitioners. Look at the female shaman's dance of the spirit in Munyô sinmu, a genre painting by Shin Yunbok (1758 - ?), while listening to the kut, a shaman ritual of healing.

Trot (Teuroteu) is the oldest type of Korean pop music originating during Japanese rule in the first half of the 20th century.