Japanese Ensemble Music

A rich tradition of hōgaku, folk, and popular ensembles persists throughout Japan. Two of the primary hōgaku genres are gagaku and sankyoku. Japanese folk music is quite popular, and a Westernized Japanese pop music scene holds a strong cultural presence.

Shomyo

First imported from China and Korea, the primary musical expression of Japanese Buddhism is called shomyo: a slow, repeating recitation of sutras, or scripture, in free rhythm. The instruments of shomyo include a large bell called a densho, which is rung with a hammer. The form is responsorial: the spiritual leader chants a section or phrase and the other monks respond. The pitch of the chant varies with the monk's voices. The monks may each sing the chant at a different pitch from the leader and from each other. The chorus is male, and the texts are sung in Sanskrit, Chinese, and Japanese. Shomyo chants are rhythmically free and may be syllabic or melismatic in style. Shomyo has had a tremendous influence on the performance practices of most of the primary genres of hogaku.

Gagaku

Gagaku, literally elegant music, is the court music of Japan. Originating 1200 years old in China and Korea, it is probably the oldest unbroken orchestral art music genre in the world. Gagaku has scarcely changed since its birth, and is still performed at the Imperial Court and in some temples.

Early gagaku imitated very closely the imported music of China and Korea. Later, during the early Heian period, its instruments and musical characteristics were modified. The instrumental music is called kangen, while music used to accompany dance is called bugaku.

The gagaku orchestra includes aerophones, idiophones, membranophones, and chordophones. The aerophones are the ryuteki, hichiriki, and sho; the chordophones include the gakuso and the biwa; the membranophones include the kakko and taiko; and, finally, the idiophone is called the shōko.

Aerophones

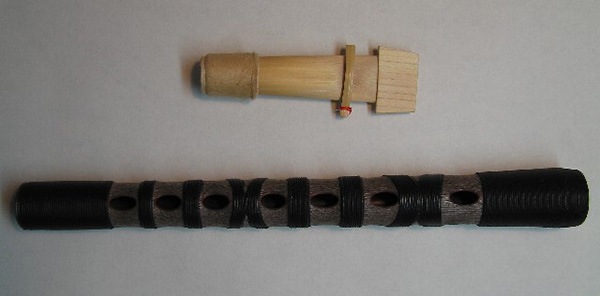

The ryuteki is a transverse flute similar to a classical Western flute. It has seven finger holes and is made of bamboo.

The hichiriki is an oboe-like aerophone with a double-reed and a piercing, distinctive timbre. It, too, is made of bamboo and has nine finger holes. There are three hichiriki and three ryuteki in a gagaku orchestra. Players of these instruments are able to bend and slide the pitches of the instruments, a technique frequently used in hichiriki performances.

The shō is a mouth organ that plays five-to six-note tone clusters designed to support the melody. The shō produces the eleven chords of gagaku using seventeen bamboo pipes equal in diameter but different in length. The pipes are encased in a circular wind chamber and connected to a metal reed whose vibrations contribute to the timbre of the instrument. Interestingly, shō players produce sound both by inhaling and exhaling through a mouthpiece located at the lower end of the instrument.

Naomi Sato demonstrates the sho [ 00:00-00:00 ]

Chordophones

The gakusō, an older version of the koto, is a six-foot long, thirteen-stringed zither, which is tuned by six movable wooden bridges. The strings are plucked by three bamboo picks attached to the player's fingers.

The biwa is a pear-shaped four-stringed lute with a flat back and silk strings. The strings, plucked with a wooden plectrum, emit a loud and crisp tone.

Membranophones

The kakko is a barrel drum played on a stand with two sticks that strike both heads. The kakko player conducts the gagaku orchestra and, as such, is responsible for setting the tempo of the piece. He plays sets of accelerating rolls that you will hear in the Listening Guide.

The taiko is a large two-headed frame drum with a deep, rich timbre. The shōko is a small bronze gong that is also hung on a frame. Both the shōko and the taiko have a colotomic role in gagaku, which means that they signal cycles of phrases throughout a piece of music.

Music Example - Gagaku Guided Listening

A gagaku piece, which can last between five to twenty minutes, consists of a slow introduction, a faster developmental section, and a still faster conclusion, and is usually composed in the traditional Jo Ha Kyu form. Its slow tempo is designed to produce a feeling of peace and balance in the listener.

Active Listening of Etenraku:

Etenraku is an instrumental Hogaku piece and the most famous and best-known gagaku piece. In gagaku pieces such as "Etenraku", the instruments always enter in a specified order, depending on which particular section is being performed. This excerpt begins with the Ha, or middle section of Jo Ha Kyu. The introductory part, called Netori, is not played in this selection.

For those of you interested in the musical theory aspects of the piece, this selection is in the hyojo mode, which is a scale that starts on the pitch E and includes the following notes: EF#GABC#DE. It is similar to a Dorian mode that begins on E, or a Western natural minor scale except that it has a major rather than a minor 6th scale term. The rhythm is in Haya yo hyōshi, which is 4 measures of four beats each- similar to a Western 4/4 meter. See if you can count the beats in the piece- it can be difficult to do because the piece has a slow pulse, and there is a breath between the fourth beat of one measure and the first beat of the next.

Instruments of Gagaku:

Wind Instruments:

Ryuteki (transverse bamboo flute)

Hichiriki (oboe)

Sho (mouth organ)

Stringed instruments:

Sō or Gakusō (zither)

Biwa (lute)

Percussion instruments:

Kakko (small drum)

Taiko (big drum)

Shoko (gong)

What to Listen for:

Melody: The melody is introduced by the ryuteki, and then repeated when the ryuteki is joined by the hichiriki. Practice listening to the recording a few times, and see if you can sing some of the melody!

Rhythm. Etenraku is in groups of four, but notice that there is a slight 'breath' between every fourth beat and the following beat one. This is a technique referred to as 'breath rhythm', a technique characteristic of gagaku. It is particularly apparent in the first two phrases of this selection. Notice the correlation between this gagaku breath rhythm and the free rhythm phrases of the honkyoku shakuhachi piece in the following listening selection.

See if you can identify the different sounds of the two drums, the higher pitched kakko and the lower pitched taiko, when they enter the ensemble. The shoko (gong) comes in with the kakko, but you will notice that it is very difficult to hear the shoko in this recording. Notice the slow and stately tempo of the piece.

Identify the timbre of the sho and the hichiriki when they enter the piece. Do they remind you of any Western instruments? If so, which ones and why? If not, what difference do you notice between these instruments and the Western instruments you are familiar with?

The stringed instruments enter last. You will notice that the biwa, the lute, enters playing an arpeggio, and is higher pitched initially than the gakusō. Stringed instruments in a gagaku orchestra play short structural motifs that support both the melody and the rhythm.

Composer: Kyoto Imperial Court Music Orchestra

-

"Etenraku"

Composer: Kyoto Imperial Court Music Orchestra

-

"Etenraku" [ 00:00-00:07 ]00:07

Ryuteki enters and introduces the melody. Notice the long, sustained quality that many of the notes have, and the use of sliding between pitches from the fourth to the fifth and the fifth to the sixth pitch.

Composer: Kyoto Imperial Court Music Orchestra

-

"Etenraku" [ 00:08-00:12 ]00:04

The kakko enters- this is also where the shoko traditionally enters Etenraku, but it is difficult to hear in this recording.

Composer: Kyoto Imperial Court Music Orchestra

-

"Etenraku" [ 00:13-00:51 ]00:38

The taiko joins with one deep tone

Composer: Kyoto Imperial Court Music Orchestra

-

"Etenraku" [ 00:52-00:53 ]00:01

Sho enters plays chords in a tone cluster that supports the melody

Composer: Kyoto Imperial Court Music Orchestra

-

"Etenraku" [ 00:53-01:29 ]00:37

The hichiriki enters, replaying the melody with the ryuteki

Composer: Kyoto Imperial Court Music Orchestra

-

"Etenraku" [ 01:30-01:36 ]00:06

At the beginning of the third rendition of the melody, the biwa enters, playing an arpeggio of notes that complement the pitches of the melody.

Composer: Kyoto Imperial Court Music Orchestra

-

"Etenraku" [ 01:47-04:22 ]02:35

The gakusō enters, playing tone clusters that support the melody.

As the piece continues:

- Notice pitch differences between what you hear in this piece and what you may normally hear in Western tuning.

- Notice the sliding between pitches, utilizing microtones between the primary notes.

- Notice the repeat of the melody- how many times in this selection do you hear it repeat?

- Notice the repeating kakko drum rolls. Does each one speed up or slow down as it progresses?

- Notice where the taiko plays its beats. These low, deep strikes are colotomic in quality, which means that they mark off specific rhythmic cycles, or time intervals, in the piece. Other examples of colotomic structure are found in the gamelan of Indonesia.

Sankyoku

Sankyoku is probably the most predominant and important genre of Japanese chamber music. Sankyoku ensembles date back the 17th century; its instruments, however, have changed over time. The hitoyogiri, preceded the shakuhachi, or kokyu. The name generically refers to a long- necked Japanese lute. Before the late 19th century, the hitoyogiri played along with the koto and the shamisen. A kokyu was a bowed, three-or four-stringed instrument that looked like a small shamisen. The kokyu and the hitoyogiri could sustain notes that the koto and shamisen could not. Once it became secularized in the late 19th century, the shakuhachi, which could also sustain long notes, replaced the kokyu and hitoyogiri. The beauty of sankyoku comes from the lovely blend of the three instruments' timbres.

Much of the sankyoku repertoire was originally koto and shamisen solo music. Pieces vary greatly from lineage to lineage because composers, who doubled as performers, aurally handed down improvised melodies. Depending on the type of piece, the koto or the shamisen plays the main melody, and the other two instruments play variations of that melody. The combination results in a heterophonic texture. When koto and shamisen players sing, the instruments become subservient to their singing.

Although Bon is a religious festival in Japan, most Bon dancing songs are now secular in nature.