Classic Blues 4

Listen to Gertrude "Ma" Rainey, another classic blues singer.

The Herbie Hancock Institute of Jazz provides a table below (Credit: David Baker) that reviews the significant differences between Country and Classic blues: Comparison of Rural and Classic Blues Style.

| RURAL BLUES | CLASSIC BLUES |

|---|---|

| 1. Black Folk society | 1. City society |

| 2. Product of an agrarian society and attendant subject material | 2. Urban environment |

| 3. South | 3. North |

| 4. Usually pure and an extension of folklore and folk song | 4. Shows an assimilation of a great many elements of popular music, including popular theater and/or vaudeville |

5. Usually find blues singers in three contexts:

|

5. Professional blues singers found in nightclubs, bars, at social affairs, etc. |

| 6. Usually men | 6. Originally mainly women; both men and women |

| 7. In-group directed | 7. Audience directed |

| 8. Broader variety of subjects | 8. Often sex oriented, though veiled |

| 9. Songs about boll weevils, drought, crops, etc. | 9. Songs about bed bugs, roaches, rats, "the block," etc. |

| 10. Bad diction, malapropisms, faulty rhyme, etc. | 10. Sophisticated speech, smooth diction |

| 11. Bleak, austere, but often infused with hope | 11. Hard, cruel, stoical, often speaks of hopelessness |

| 12. Stringing together of stock phrases; lines often disjunct and unrelated | 12. Emphasis often on lyrics that tell a story |

| 13. Rough style | 13. Smooth, theatrical style |

| 14. Harsh, uncompromising, raw | 14. Contains diverse and conflicting elements of black music, plus smooth emotional appeal of performance |

| 15. Improvised | 15. Standardized, formalized, etc. |

| 16. Less structured, "free" form | 16. Classic six, eight, or twelve-measure form |

| 17. Use of pedal points, chord drones, prolonged and indefinite rate of harmonic change | 17. Standard blues changes: I IV I V IV I |

| 18. Unaccompanied voice, or mostly solo, with guitar accompaniment; also ad hoc instruments | 18. Instrumental accompaniment using conventional instruments |

| 19. Spontaneous expression of thought and mood | 19. Written material, formal orchestration, musical arrangements |

| 20. Spontaneous beginnings, fade-away endings | 20. Clear cut beginnings (includes use of introduction) and endings |

| 21. Structural elaboration is usually accidental | 21. More elaborate structures (tags, endings, modulations, etc.) |

| 22. Expressive rubato and erratic tempi | 22. Wide tempo choices, but rigidity once established |

| 23. Melody straight, range relatively narrow and confined; nasal quality with restricted use of melisma | 23. Melody influenced by instrumental practices; wide range and extensive use of melisma |

| 24. Rhythms crude, simple, and erratic | 24. Rhythms sophisticated, refined, often standardized |

| 25. Scale choices relatively limited -- usually blues, pentatonic, major | 25. Greater scale choices -- blues, pentatonic, diminished, etc. |

| 26. Greater use of vocal ornamentation for personalization (growls, slides, etc.) and to relieve the monotony of solo voice and solo instrument | 26. Stricter vocal technique |

| 27. Solo or ad hoc instruments | 27. Groups usually organized |

| 28. Usually "in-group" Black | 28. More readily acceptable to and adapted by White world |

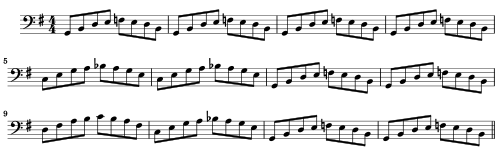

The most striking and individual piano blues style was the "boogie-woogie," (Example: "Pinetop Boogie Woogie ") which was probably so named after a dance. Its main feature was using a powerful left-hand rhythm characterized by having eight beats to the bar. Variants of this included the "walking bass" and a bass figure reflecting the rhythms of the Spanish habanera, developed by a Chicago pianist, Jimmie Yancey, as exemplified on his " Slow and Easy Blues ." It is possible that the boogie style evolved in Kansas City, home of the notable pianist Albert Ammons, and also Pete Johnson, who frequently accompanied the "blues shouter" Joe Turner. Nevertheless, many boogie pianists worked the barrelhouses, or crude bars, run by the timber-producing companies in their "logging camps." These temporary accommodations, which Black workers generally staffed, were relocated when the trees in one area had been felled and logged. As a result, the industry flourished in Louisiana and east Texas. Eurreal "Little Brother" Montgomery was one celebrated blues and boogie pianist born in a Louisiana timber camp (Oliver 2012, n.p.).

Although there are many variations, the basic boogie-woogie bass pattern is a two-bar pattern using quarter notes. The bassline ascends and then descends strongly, outlining the notes of each dominant 7th chord in the blues progression. The basic two-bar pattern goes: | Root-3-5-6 | b7-6-5-3 |. A classic example of this style can be heard in Eurreal Montgomery's " No Special Rider ."