The Spread of Jazz

Spread of Jazz

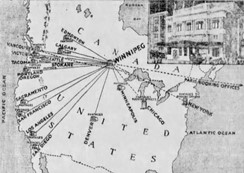

New Orleans musicians took these home-grown practices with them as they left to seek their fortunes in Chicago, New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. They adapted as necessary once detached from local functional imperatives and exposed to new markets' demands, and thus idiom of jazz further evolved.

The dissemination of New Orleans jazz beyond the region was accomplished primarily by diffusion, which provided access to phonograph records that accelerated and expanded the process. Before the first jazz recording by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band in New York in February 1917, New Orleans musicians had already traveled extensively throughout the United States. "Jelly Roll" Morton left the city in 1907 and roamed everywhere; the Original Creole Orchestra toured the Pantages vaudeville circuit during 1914 to 1918, and Tom Brown's Band from Dixieland was active in cabarets and theaters in Chicago and New York in 1915. Yet after the initial jazz records sold widely, everyone appreciated the importance of the phonograph. Consequently, enclaves of New Orleans jazz musicians in Chicago, New York, and elsewhere exhibited the same penchant for experimentation on recordings that informed their earlier experiences at home.

In Chicago, King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band (1922-1924) relied exclusively on head arrangements to prepare for recording sessions. Head arrangements can be defined as the section where all or a particular group of instruments would play the main theme of the composition after individual solos are performed. Though charted out, these sections are usually memorized. On the other hand, Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five (1925-1928) combined occasional use of scores, head arrangements, and spontaneous ideas generated in the studio to enliven its recordings. Morton had his Red Hot Peppers rehearse with scores but expected some players to improvise in select passages, inserting their "voices" where Morton wanted them.

After 1925, recordings made in the Chicago region by the Hot Five, Morton's Red Hot Peppers, and King Oliver's Dixie Syncopators could all be considered variants of New Orleans style. Still, the contrasts were notable-each group had a pronounced sound of its own.

Back in New Orleans, recordings made after 1925 illustrate equivalent diversification among bands in the city. These include recordings by the Halfway House Orchestra, Sam Morgan's Jazz Band, the Original Tuxedo Jazz Orchestra, the New Orleans Owls, John Hyman's Bayou Stompers, and the Jones & Collins Astoria Hot Eight. None of them sounded like the New Orleans-derived bands in Chicago.

Louis Armstrong

Very few of the men whose names have become great in the early pioneering of jazz and of swing were trained in music at all. They were born musicians: they felt their music and played by ear and memory. That was the way it was with the great Dixieland Five.

Heebie Jeebies

Say, I've got the Heebies

I mean the Jeebies

Talking about

The dance, the Heebie Jeebies

Do, because they're boys

Because it pleases me to be joy