Historical and Cultural Convergences 1

An appreciation of the correlation of regional culture and musical function is necessary to understand the historical development of New Orleans jazz, and jazz music in general. Understanding this correlation requires a close examination of neighborhood affiliation and festival traditions, rural and urban connectedness, and shifting social conditions during a time of intense technological change. For example, technology such as the emergence of the "trap" drum set at the end of the nineteenth century and the mechanical dissemination of music via phonograph recording in its first boom era (roughly 1890-1928) influenced band instrumentation. Furthermore, these and other developments also fostered a unique playing style in New Orleans based on improvisation.

Even before its acquisition by the United States in 1803, New Orleans was a "music" city, as demonstrated by French and Spanish bals (dances), masques (masked dances), resident opera and ballet companies, military parade bands, and all manner of ambient serenading. New Orleans's situation as a cultural crossroads was apparent in the music it generated. Before the Civil War, the public spectacle of before mentioned government-regulated "ring shouts" at Congo Square underscored an exceptional degree of African and Afro-Caribbean musical sensibility present in the city. By the late 1830s, one could hear the Black street crier Signor Cornmeal alternated with French and Italian opera at St. Charles and Camp Street Theaters-even slaves (with fifty cents) could attend these performances. Such diversity was the product of history and geography. Throughout the nineteenth century, the city absorbed the benefits of three cultures: a Gulf/Caribbean Créolité that tied New Orleans to Cuba, Haiti, and Central America (evident in the compositions of Louis Moreau Gottschalk and imported Mexican danzas and Cuban danzón published locally); the North American vernacular that flowed down from the heartland via the Mississippi River (including "alligator horse" ballads, minstrelsy, work songs, and, later, the blues); and the trans-Atlantic connections that brought the most fashionable European popular music (such as that of first-run ballets and opera or Jenny Lind).

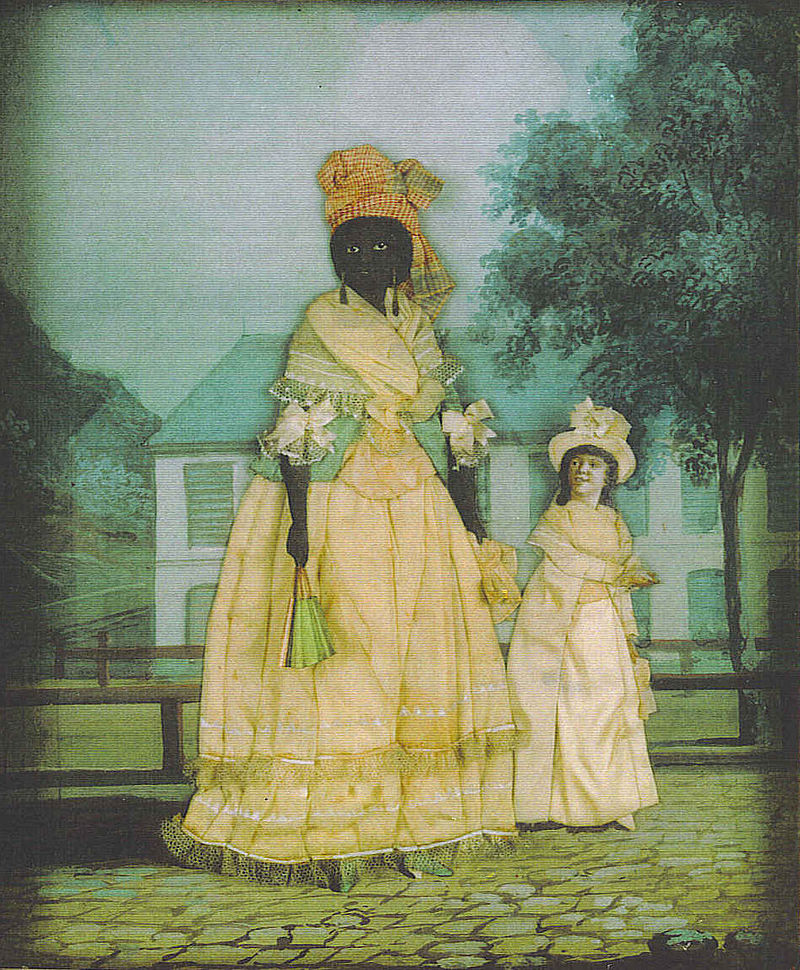

The city's location also reflected its social complexity. During the nineteenth century, there existed a context of racial and cultural ambiguity that persisted after the Civil War and Emancipation. This situation came about as a result of the contested status of Afro-French Creoles, most being gens de couleur libres (free people of color), set against urban African American slavery (and related possibilities of freedom from slavery and plaçage A recognized extralegal system in French and Spanish slave colonies of North America (including the Caribbean) by which ethnic European men entered into civil unions with non-Europeans of African, Native American and mixed-race descent. or racial intermingling). In an attempt to establish a strictly biracial system of separation, the state legislature passed the 1890s Jim Crow laws (underwritten by the U.S. Supreme Court's validation of segregation in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896). Indeed, most accounts of the emergence of jazz in New Orleans attribute it to the forced collaboration of musically literate "downtown Frenchmen" (Creoles) and musically intuitive "uptown Blacks" (African American freedmen and migrants from rural parishes), inherent in racial leveling, civic disenfranchisement, and economic dislocation.

Heebie Jeebies

Say, I've got the Heebies

I mean the Jeebies

Talking about

The dance, the Heebie Jeebies

Do, because they're boys

Because it pleases me to be joy

Wynton Marsalis

Jazz music is the power of now. There is no script. It's conversation. The emotion is given to you by musicians as they make split-second decisions to fulfil what they feel the moment requires.