Classic Blues 3

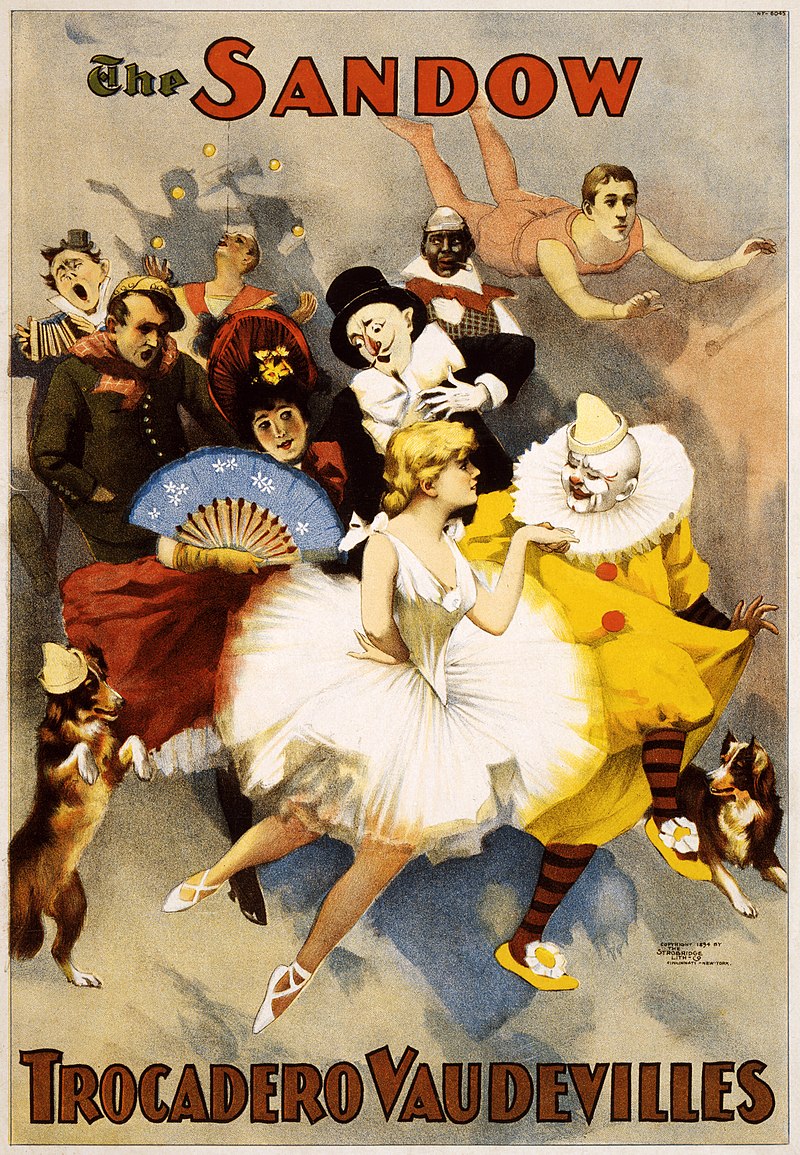

Vaudeville This term had its origins in Paris in the early eighteenth century and referred to the songs performed at the Théâtre de la Foire (Fair Theatre) and the Opéra comique that put new lyrics (with timely subjects) to well-known melodies. As Opéra comique became it's own musical genre using original music in the nineteenth century, vaudeville then referred to comedies with songs thrown in. This form of entertainment was popular into the early twentieth century. Today, vaudeville is generally thought of as a variety show with unrelated acts consisting of stand-up comedy, virtuoso instrumental and vocal performance, and song and dance acts. is occasionally written about in connection with the early blues. Solo and duo acts were sometimes billed as "vaudeville," only to be replaced by a reference to "variety shows" or "revues." Such changes in the titles were mainly to attract the attention of readers of the New York Times and other northeastern newspapers, than to be specific as to the nature of the performances (Hoffmann 1983, n.p.). It was probably the occasional references to vaudeville in studies of American theater and show business that led to the use of the word in books on blues and blues singing. Where this occurs it is customarily in association with the singing styles of some of the earliest blues artists on record, indicating singing with a somewhat stage-mannered delivery, rather than with a quality that was expressive both of the feelings of the singer and of the content of the blues as in slightly later blues songs.

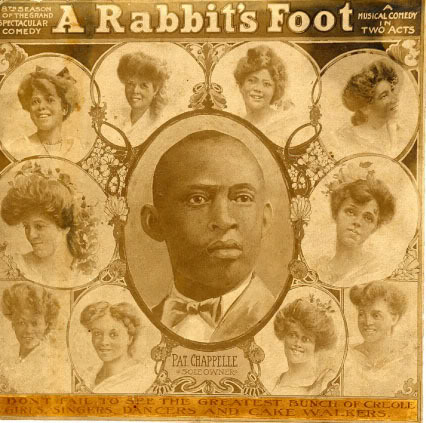

The early history of blues was marked by the singers' relationship to the professional stage, often promoted by the African American-directed Theater Owners Booking Agency (or TOBA). Exposing large audiences throughout much of the East, the Midwest, and the South to their repertoire, manner of expression, and delivery did much to popularize the new idiom among African Americans. Many large shows, including Ma Rainey's, traveled in their own railroad cars. Other companies traveled in "tent shows," which could perform under canvas in smaller locations. Other shows, with varied vaudeville casts, included blues singers. The Florida Cotton Blossoms show, for example, featured the iconic blues singer Ida Cox. Traveling companies that recruited new artists every year included "A Rabbit Foot Minstrel Show," founded in 1890 by Patrick Chappelle from Florida and developed later by Fred. S. Wolcott, a farmer of Port Gibson, Mississippi. Equally famous was "Sugar Foot Green from New Orleans," which, despite its name, although it did not emanate from New Orleans but North Carolina.

While the Classic Blues style of singing and expressing the blues already appeared dated to some listeners of the period, the singers' traveling had done much to spread the blues idiom across the U.S. However, the majority of blues singers did not record after the retirement of Ma Rainey and the tragic death of Bessie Smith in an automobile accident in 1933. Ida Cox and Victoria Spivey were among a small number of exceptions, who continued to work with traveling shows until the United States entered World War II.

A few surviving, if retired, Classic Blues singers were briefly recorded and interviewed in the post-war years, primarily for their appeal to collectors or to satisfy the curiosity of blues historians rather than their former audiences. Yet their importance in the evolution, the expression, and the diffusion of the idiom is without question.

Bo-Weavil Blues

Hey, bo-weavil, don't sing the blues no more

Hey, hey, bo-weavil, don't sing the blues no more

Bo-weavil's here, bo-weavil's everywhere you go

The St. Louis Blues

I got them Saint Louis Blues

just as blue as I can be

He's got a heart like a rock cast in the sea

Or else he wouldn't have gone so far from me